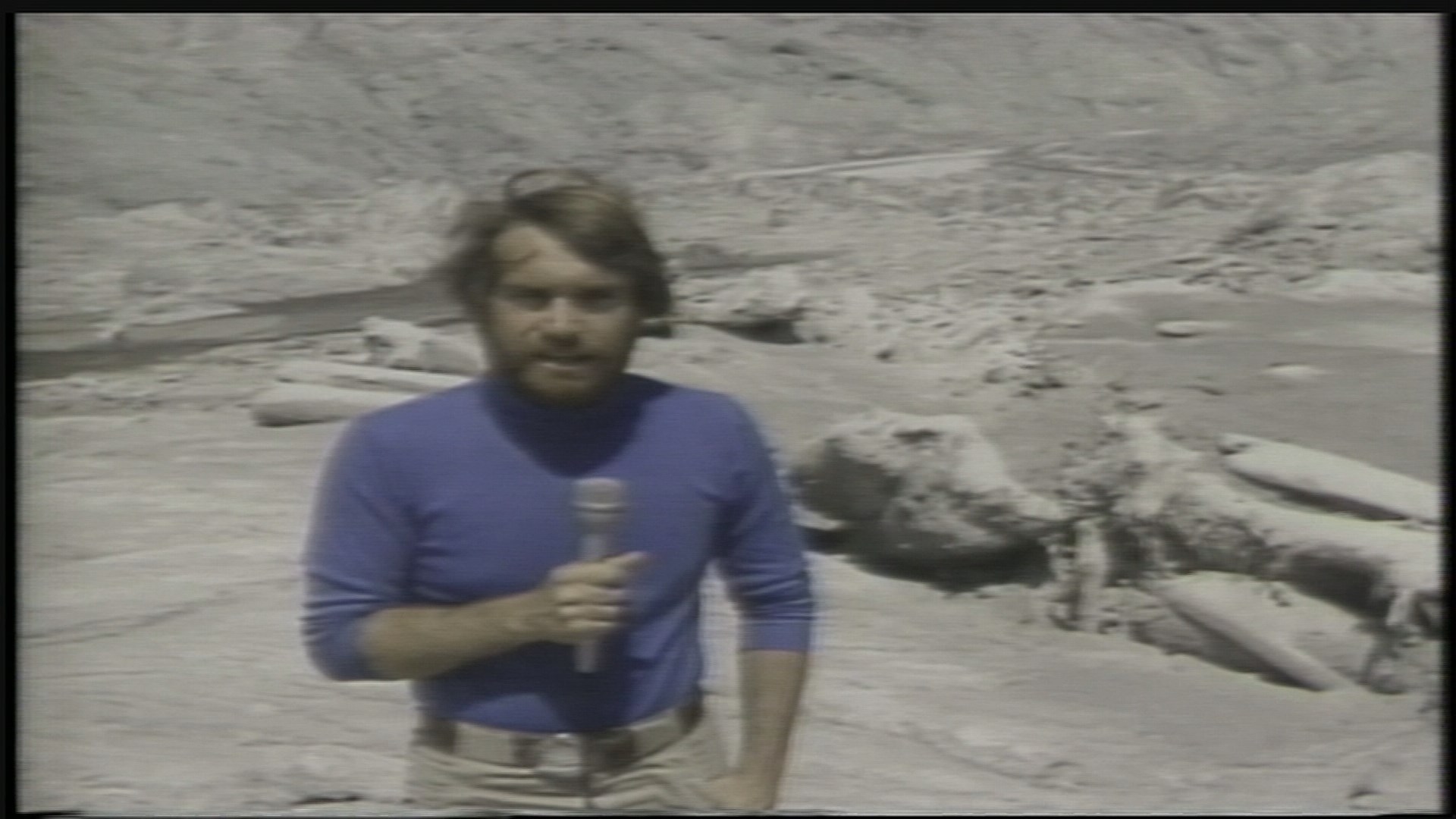

![635672176862581930-JeffRennerin1980report[ID=27320413] ID=27320413](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/63db19bf99c398b98bab478830e58cbf125ba221/c=216-31-1424-1064/local/-/media/2015/05/14/NWGroup/KING/635672176862581930-JeffRennerin1980report.JPG)

As the KING science reporter, I was teamed with photographer Mark Anderson and engineer Mike Carter. We moved progressively closer to the volcano as the activity level increased from mild steam or 'phreatic' eruptions to earthquakes and showers of pumice which pelted our tent.

During our occasional returns to Seattle, I stocked up on Geology and Volcanology texts to aid me in deciphering and explaining Mount St. Helens' stirrings in our nightly broadcasts from our ridge top locations overlooking the volcano. Keep in mind there was no generally available internet in 1980, and certainly no WiFi! When we could connect with visiting scientists, we eagerly grabbed those opportunities to gain more perspective and information that we could share with our viewers.

We had left the volcano on Thursday, May 15, because it had entered what seemed to be a quiet period. No activity was expected and our crew looked forward to a rare quiet weekend at home. However the next day, it was announced that property owners would be escorted into the Red Zone that weekend by the state patrol. Reports of vandalism and theft had led to increased pressure on then-governor Dixie Lee Ray to allow the inspections tours. Given our familiarity with the story, the area and the people, we agreed to return.

It was a beautiful Saturday. The growing bulge on the north side of the volcano evident, the glacier ice cracked by the strain, black ash dusting the flanks of Mount St. Helens. As we talked with property owners at Spirit Lake, the volcano gave no sense that it was about to explode. If we had suspected that, we undoubtedly would have stayed. If we had, I wouldn't be here to write this.

The next morning, my wife and I felt a 'thump' that shook the windows in our home in Redmond. Seconds later it seemed, my phone rang. It was a man named Carl Berg, who lived close to the volcano. "The mountain is erupting, Jeff-the sky is filled with black ash."

Still sleepy, I knew there had been ash eruptions before and changes in wind direction could carry it where it hadn't fallen before. "Thanks, Carl…if it continues for more than a few minutes…call me back."

I didn't want to discourage Carl, but it didn't make sense to spend expensive helicopter time only to find it was only another ash eruption and that it was over by the time we arrived.

Seconds later, the phone rang again. "There's lightning coming out of the eruption cloud, Jeff". I recognized this as the sign of a massive eruption, the lightning generated by ash particles violently jetting out of the volcano.

Flying over the destruction

Calls were made to KING and in a short time (we'll not discuss just how fast I drove), photographer Mark Anderson and I were in the station helicopter flying to Mount St. Helens. What began as a thin brown line on the horizon broadened into an expanding layer of ash in the air -- that quickly lowered. The volcano was invisible, cloaked by ash.

Knowing the expanding bulge on the north side was likely to be the source of the eruption, we headed toward up the North Fork of the Toutle River. But increasing ash forced us back. We knew the sharp ash particles could ruin the helicopter engine. An emergency landing under such conditions wasn't a good idea.

We diverted to the South Fork of the Toutle River where the visibility was slightly better. We were stunned to see the river choked with mud and debris. Although the volcano still wasn't visible, the ash cloud had lifted enough that we moved back up the North Fork. The mudflow was a raging torrent, the once green surrounding river banks, hills and mountain ridges unrecognizable in a coating of gray-brown ash and mud. We tracked one stretch of mudflow at more than forty miles per hour.

Motion caught my eye. "Mark," I called to my photographer, "look at that tree." A huge Douglas fir was shaking, vibrating, under the force of the mudflow, ash shaking out of its limbs with each tremble. Suddenly, it toppled over. That image, that scene, has been borrowed and used in countless documentaries since that day.

A huge ooze of red, like a pool of blood, caught our attention next. We recognized it as coming from a Weyerhaeuser logging site-the force of the mudflow had ripped open hydraulic fluid storage tanks, scattering huge tractors and other machinery like miniature toys.

The day became a blend of attempting to catch glimpses of what exactly had happened to the volcano. Although the lower slopes could be seen, the upper slopes remained obscured by ash clouds. We documented damage and responded to requests for help (we evacuated the wife of a helpful local via helicopter with their chickens -- something that we did not document on video tape).

Throughout the activity we attempted to simply comprehend the scale of the destruction, to weave the many threads of what we were seeing into a story we could tell in words and video on television. We all were suffering from a sense of disconnect. What had been a lush alpine wonderland had seemingly disappeared -- the bottomless blue lakes, the endless green of ridge after ridge covered by firs, shrubs and alpine wildflowers, and the beautiful symmetrical white cone of the glacier covered volcano -- all gone. Only muted shades of gray, brown and black remained.

There was not a single sign of life remaining. It was next to impossible to even locate our past broadcast locations. All of them had either been swept clean of recognizable landmarks, or buried beneath feet of ash and pumice. We're not speaking of a valley or two; we're talking about the equivalent of all of King County -- and perhaps some of the neighboring counties -- blasted into the basement of time, a prehistoric past none of us knew, long before life emerged. If a dinosaur suddenly emerged over one of the ridges, I don't think we would have been shocked. The destruction was that total.

We were evacuated to a peak outside Olympia for our broadcasts. I had a sense of going through the motions, still unable to fully integrate what I'd seen and heard and done.

Just prior to my first broadcast, our engineer came up and gently whispered "your friend David Johnston is missing and believed dead. The USGS thinks he was blown off his observing post by the force of the blast." David was a USGS scientist I'd come to know, respect and like. We shared similar interests and backgrounds. What were simple numbers on the list of suspected dead and missing suddenly took on profound personal meaning.

I tried to shelve the sense of denial, the sense of personal grief as we did broadcast after broadcast, but the numbness was always present. Continued busyness was the best antidote. And there was plenty to do. Sleep that night came quickly, but was shallow and restless.

The next morning, we met our helicopter pilot for a post dawn flight into the destruction zone. The volcano had, for the time, gone quiet. The ash had settled. Even after the experiences of the day before --the eruption day -- we weren't prepared for the scale of the destruction. It stretched for miles in all directions. We felt like we were flying over the barren landscape of a young, new planet. It was difficult to believe the volcano ahead of us -- blunt, barren of color, ash pouring out of its north side like an open wound -- could possibly be Mount St. Helens.

And it seemed even more difficult to believe this area could ever support life again. But it would…and it has.

![Jeff Renner remembers Mount St. Helens eruption [ID=27394429]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/smartembed.png)