KING COUNTY, Wash. — A King County department that responds to medical emergencies involving high-risk patients is under federal oversight after a paramedic fatally overdosed last year on controlled drugs that he likely stole from work, according to county and federal records.

A Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) investigation, triggered by the February 2023 death of the King County Medic One paramedic, Alexander Genschaw, found Medic One’s safeguards and procedures “failed to prevent the theft and diversion of controlled substances” as required by law.

In July 2023, the DEA and King County Medic One entered into a “Memorandum of Agreement,” an administrative tool that the federal agency uses in diversion cases to enforce and oversee changes to policies and protocols involving controlled substances. The settlement, which remains in effect through next July, required Medic One to update its controlled medication policy and take other steps to prevent future drug theft, such as conducting regular audits of drug and patient records.

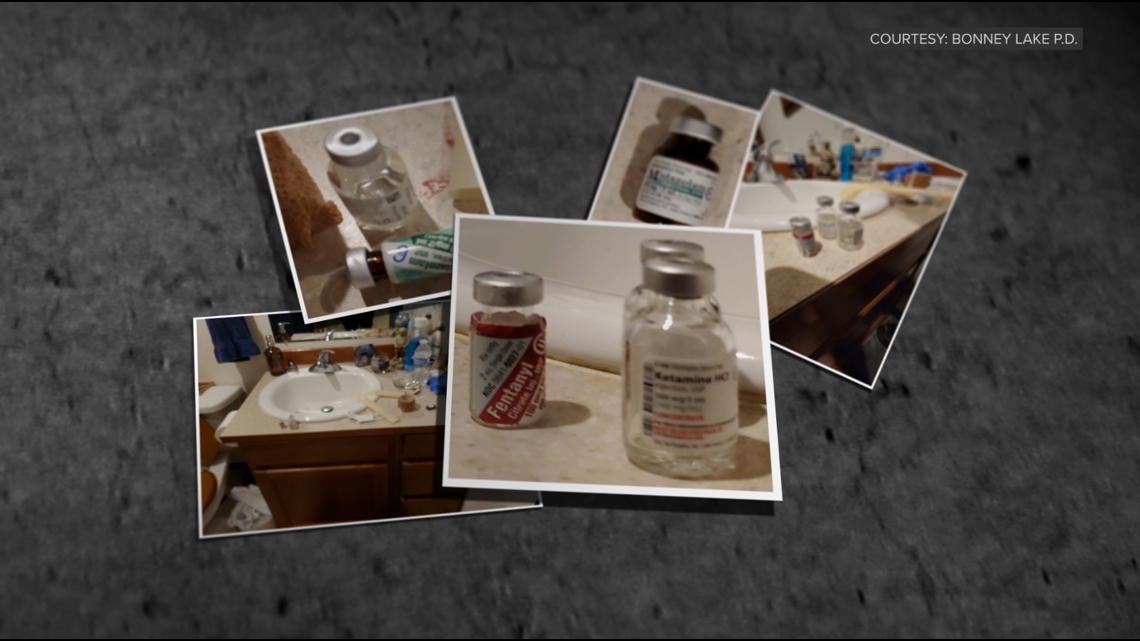

Genschaw, 34, was found dead by his girlfriend in the bathroom of his Bonney Lake home in an “apparent overdose” on Feb. 26, 2023, according to records from the Bonney Lake Police Department and East Pierce Fire and Rescue.

Police officers reported they found at the scene six vials of sedatives and pain relievers intended for critically ill patients, along with wrappers from medical supplies and an IV bag full of fluid still hooked up to Genschaw’s body. Five of the six vials of controlled medication, which included Ketamine, Fentanyl and Midazolam, were empty.

Medics and officers at the scene commented on their surprise to find the medication in containers that are typically only found in medical settings, and they observed there was "absolutely a lethal dose" of drugs in Genschaw's possession, according to police audio captured on body cameras.

“It looks like he most likely took this from work,” one Bonney Lake officer said.

Five days later, King County Medic One leaders notified the DEA that they conducted a drug audit and found no missing medication or discrepancies in their records. But they suspected Genschaw was “likely diverting” medication that belonged to the agency, according to King County records. Diversion refers to instances where controlled substances are taken by someone they aren’t prescribed to.

The identifying numbers on the vials found at Genschaw’s home – three vials of Ketamine, two vials of Midazolam, and one vial of fentanyl – matched King County Medic One’s record of medication delivered to the agency for patient care, county records show. Because thousands of vials around the country have the same identifying numbers issued by drug manufacturers, Medic One leaders said they can’t say with certainty that the vials found in his home belonged to the agency.

"We assume that it was ours,” said Andrea Coulson, the chief and paramedic service administrator at King County Medic One.

Coulson said Medic One suspects that after giving medicine to patients, Genschaw pocketed the drugs that were left over in the vials instead of properly “wasting” them – a standard process in the medical field that ensures unused drugs are thrown out and irretrievable.

“We have had no indication that any of the patients were put at risk,” Coulson said. “We’re very certain that there were no adverse effects to the patients he treated.”

Medic One had ‘no indication’ of substance abuse problems with Genschaw

King County Medic One responds to emergency calls around King County when patients in crisis need advanced medical care on the way to the hospital. The department is managed by Public Health – Seattle & King County.

Compared to EMTs, Medic One paramedics have more extensive training that allows them to perform advanced procedures on patients dealing with issues like gunshot wounds, cardiac arrest and severe respiratory problems. Medic One paramedics can also give patients powerful anesthetics and pain relievers.

But under federal law and King County policy, access to that medication is supposed to be tightly controlled.

At the time of Genschaw’s employment, Medic One policy required its drugs to be securely stored in safes on paramedic rescue trucks. The department relied on a buddy system to protect its medication – requiring two paramedics to witness and document every time drugs were used on a patient or removed from the safe.

The policy also required the two paramedics to observe and sign off that any medication leftover in the syringe was properly “wasted” – usually either by spraying it out on the ground or the garbage. Experts said wasting medication is one of the most common ways controlled substances are diverted in health care settings.

Coulson said she found no evidence that any Medic One staff, aside from Genschaw, violated Medic One’s drug policies in this case. King County leaders said they believe he stole the medicine without his co-workers’ knowledge, but Coulson said exactly how it happened is a “mystery.”

“There was no indication whatsoever that Alex had an issue,” Coulson said.

Genschaw, was a new paramedic at Medic One, hired in July 2022 after working elsewhere as an EMT. He was on probation – a temporary status given to Medic One’s new hires, which typically comes with extra training and oversight.

"He was just starting to become a paramedic with us, but what I knew was a very inquisitive, quirky, fun man who was just getting started in this profession," said Evan Van Otten, a King County paramedic and Medic One division chief. "It broke all of our hearts that this happened to our own."

Not Medic One’s first case of drug misuse

It’s not the first time King County Medic One has had trouble keeping its drugs secure from its own staff’s misuse.

In 2016, former King County Medic One paramedic Paul Ahrens was sent to prison after a federal conviction of tampering with consumer products for stealing morphine, midazolam and lorazepam from Medic One’s vials and replacing them with other drugs.

Court sentencing records detail five instances in November 2013 that Ahrens withdrew morphine from vials, used them for himself and replaced the liquid with something else that would not have provided patients with proper pain relief.

“Regardless of all the stop gaps that you put in place, you cannot prevent diversion,” said Coulson, who became Medic One’s chief in 2022 after working as a paramedic for the department. “If someone wants to divert, they will find a way around it.”

Heather McMurry, diversion program manager for the DEA’s Seattle Field Division, said her office received 98 reports last year of employee drug theft in Washington’s healthcare industry. It’s unclear how many of those reports of employee theft led to a DEA investigation or enforcement action.

“Any employee theft is significant because that means there is a lack of security or accountability.” McMurry said.

The Washington State Department of Health (DOH) reports it received 15 diversion complaints about the state's paramedics and EMTs over the last 10 years. DOH took some form of enforcement action against provider licenses in five of those cases, according to data provided by the agency.

McMurry said it’s most common for the DEA's diversion unit to receive reports of theft occurring in hospital-like settings, where more medical professionals have access to controlled substances.

“First and foremost, our job is to go and make sure that it doesn’t happen again – that they’ve implemented policies, that they’ve got better security,” she said. “It comes down to patient safety ... and in a healthcare setting, where people are vulnerable and they’re sick … it’s important we do our job to make sure they are actually getting the medication they need.”

King County changes

In November, King County Medic One updated its drug policy to comply with stipulations of its agreement with the DEA. The agreement allows for the federal agency to conduct unannounced inspections of Medic One operations.

Coulson said Medic One has strengthened its practices and equipment to better track inventory of its medication and who is handling it.

"I have no concerns or evidence about substance abuse within our organization," Coulson said.

In one of the biggest changes since Genschaw's death, Medic One upgraded to an electronic system that tracks, in real time, who from the department is accessing controlled drugs from the safes and when. Previously, the department used a manual system to track its drugs.

Medic One also added labels with unique identifiers to each of its vials of medicine so if missing drugs turn up in the future, there’s no question where they came from.

King County also refined its policy for wasting unused drugs.

Under the new policy, two paramedics need to witness, record and sign off on the disposal of all leftover controlled substances – not on the ground or in the garbage, but in a dedicated container that will also store the physical syringe and the vial that originally held the medicine.

The new policy requires the process to be done electronically, with each paramedic signing off using their unique pin number.

"We don't want to see this happen again," Van Otten said.