Twenty years ago, the Makah Indian Tribe hunted and killed a gray whale, touching off both pride and protest around the world. The tribe is attempting to do it again.

Over the next several days, lawyers for the Makah Tribe will try to convince a judge in Seattle that they should be able to resume their hunt of gray whales, while animal rights activists will work to convince him otherwise.

Thursday was the first day of testimony that is expected to stretch into next week. It’s a battle that has spanned decades. Much of what will happen in court can be traced back to a single day in 1999 when the eyes of the world set upon Neah Bay, Washington.

Its legacy lasts to this day.

THE 1999 MAKAH WHALE HUNT

The Makah have hunted whales in the waters off Neah Bay for thousands of years. A treaty signed with the U.S. government in 1855 gives them the legal right. The tribe voluntarily stopped hunting in 1922 when whale populations dropped, due largely to commercial overfishing.

“It’s hard to explain. When you grow up by the ocean, it’s kind of ingrained in you. It’s who you are,” explained Makah Tribe Treasurer Patrick Depoe.

Like most Makah, Depoe feels a part of the Pacific Ocean.

“The ocean is what’s important to us,” Depoe said, walking in the wind and rain along the sandy coastline on the Makah Indian Reservation. “This ocean is who we are.”

What the ocean provides is at the core of the tribe’s values.

When gray whale numbers rebounded in the 1990s, the Makah decided to observe its treaty rights and hunt once again.

“Makahs have always been whale hunters and we always will be whale hunters,” said tribal member Janine Ledford.

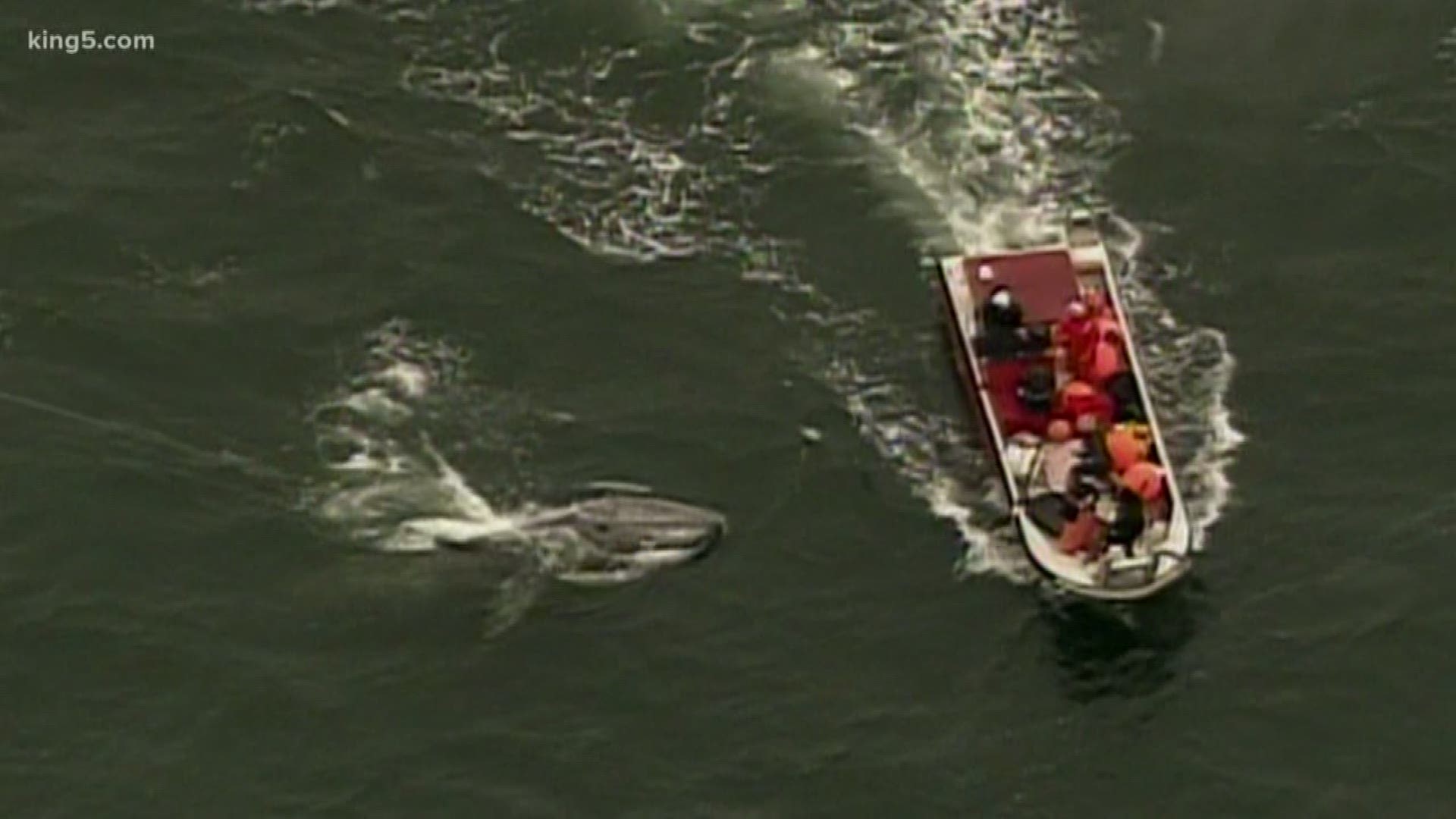

The 1999 announcement to hunt the whales again was met with outrage from animal rights groups that battled the tribe with protests on land and at sea. The Sea Shepherd Society launched protest boats on the Pacific Ocean, touching off a sometimes-dangerous game of cat and mouse on the open water.

After eight months of attempts to kill a whale were thwarted by protesters and weather, the Makah finally landed their catch on May 17, 1999. A team of Makah whalers in a wooden canoe, armed with harpoons and a .50 caliber rifle took its prey.

The whale was speared, floats attached so it would not sink, and then several rifle shots were fired at close range to expedite its death. The hunt made international news and was televised live on CNN around the world.

“It was an amazing feeling. It was beautiful,” said Depoe.

Depoe, who was 16 years old at the time, was on the beach when the whale was brought in, blessed, butchered and distributed to each Makah family.

“It isn’t that we’re going out there to slaughter something,” said Depoe. “It’s that we’re going out there to take part in an indigenous belief that is essential to our identity -- essential to who we are.”

IMPACT OF THE HUNT

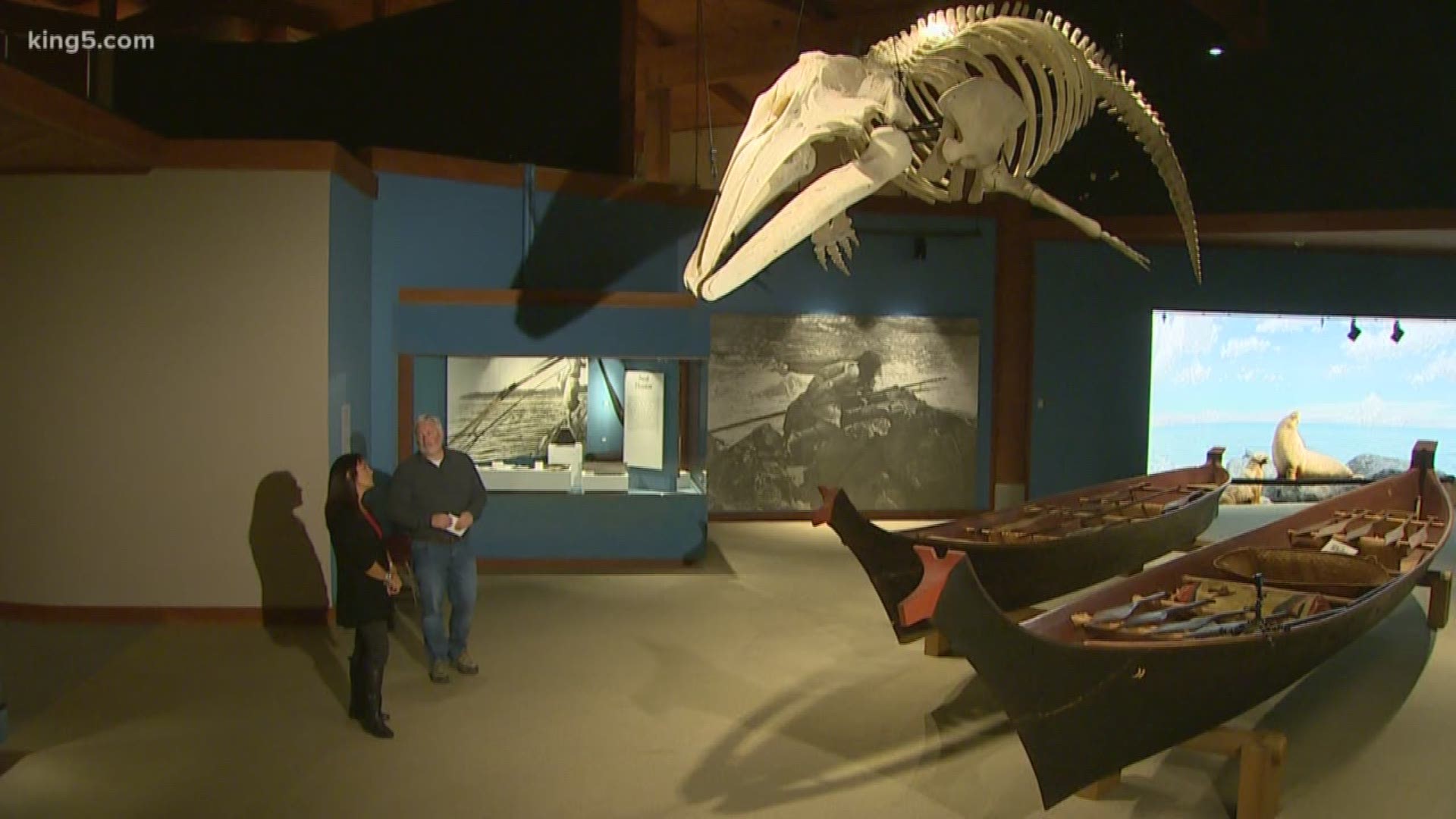

The bones of that whale now hang from the ceiling of the Makah Museum where Ledford is now executive director.

“It’s wonderful to think that this whale is right here. This whale that we took in ’99 to restart an important tradition,” said Ledford.

Ledford was celebrating on the beach when the whale was brought ashore.

“So many people shed tears of joy. We were so proud we accomplished something we set out to do,” said Ledford. “We had seen whales being brought in historic photos only. Those of us who were there on the beach that day got to experience it and will never forget it.”

Ledford said the impact of the 1999 hunt can still be felt a generation later with a reinvigorated interest in tribal culture, especially among those born around the time of the hunt. She doesn’t think it’s a coincidence that the generation brought up since the hunt has seen four consecutive years with a 100% high school graduation rate.

While the hunt certainly isn’t the only reason for increased academic performance, Ledford said it has made a difference.

“We think there’s a connection there, where whale hunting and a focus on traditional values, language, and knowledge does connect,” Ledford said.

WHALE HUNTING GOES TO COURT

While the whale hunt was celebrated by the Makah Tribe, animal rights activists couldn’t see it more differently.

“Whaling is barbaric. Pure and simple -- it’s barbaric,” said Sea Shepherd Society’s Catherine Pruett.

Sea Shepherd tried to stop the 1999 hunt with protest boats in the water and now they’re taking their battle to court.

They’re fighting a decision made earlier this year by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that allows the tribe to kill 20 eastern Pacific gray whales every five years.

Five whales may not seem like very many out of a population of about 27,000, however, activists said the population is not stable. Pruett claims more than 5,000 gray whales have starved to death on the West Coast this year alone.

Activists also worry that the tribe could accidentally kill a whale that is not among the 27,000 eastern Pacific grays, something they believe could make more delicate populations “collapse entirely.”

The tribe must now prove to a judge that the hunt would not endanger any whale populations.

Pruett believes no one should be killing any whales, anytime, anywhere.

“We understand this has been something in their culture for a long time,” said Pruett. “But these are highly social and sensitive creatures. We should be protecting them. They’re so important for ecosystems. As a culture, we need to know not to do this.”

Pruett points to the Quileute Tribe which, she said, practices a ceremonial form of whaling where no animals are harmed.

“Even with a history of whaling, there are ways they could honor that history by doing something else,” Pruett said. “It is just unconscionable to consider killing them.”

“Once again, it comes back to cultural beliefs,” countered Depoe. “Once again, it comes back to religious freedom. It comes back to a legal right. They’re allowed to say or think or feel however they want to feel. But ultimately, it’s not their decision.”

The decision ultimately lies with a judge who will hear several days of testimony and make a recommendation to NOAA as to whether a waiver should be granted, allowing the Makah hunt to go forward.

The judge’s decision could take several weeks or even months.

Activists from Sea Shepherd said they don’t expect to prevail in this fight. They are already planning to sue NOAA to keep whaling boats out of the waters of the Northwest for as long as possible.

As tribal leaders now do battle with activists in court, they hope it won’t be another 20 years before they can celebrate their heritage once again.