For women over 21, the pap smear is an unpleasant and often painful part of a visit to the gynecologist. New research shows that the less-invasive human papillomavirus (HPV) test is a more accurate way of detecting cervical cancer.

Researchers say replacing a pap smear with an HPV test can allow women to go longer between tests and give them increased confidence they are cancer-free.

Cervical cancer cases in the United States have decreased by 50 percent since 1975, due to improved screening practices that detect pre-cancerous lesions, or pre-cancers. Even so, about 13,000 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer and 4,000 will die from the disease in the United States each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

A clinical trial published last week examined the effectiveness of two different screenings for cervical cancer. Across 19,000 participants, researchers found that testing for HPV detected pre-cancers earlier and more accurately than a standard pap smear.

Virtually all cases of cervical cancer are caused by HPV — the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States. Research from the CDC found that over 80 percent of Americans will contract HPV in their lives.

Most HPV infections clear up on their own, but persistent infections can lead to the development of pre-cancers. Not all of these pre-cancers turn into cervical cancer, but almost all cervical cancers can be prevented by treating pre-cancers.

Pre-cancers often take years or even a decade to develop into cervical cancer. Currently, women in the United States are recommended to get a pap smear every three years until age 65. For women over 30, the guidelines also allow for co-testing (a pap smear and an HPV test) every five years instead.

Since HPV is so prevalent in women in their 20s, this demographic will still have to rely on the pap smear. Otherwise, said Rachel Winer, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Washington School of Public Health, “You would just have a lot of false positives and be over-referring women for further testing.”

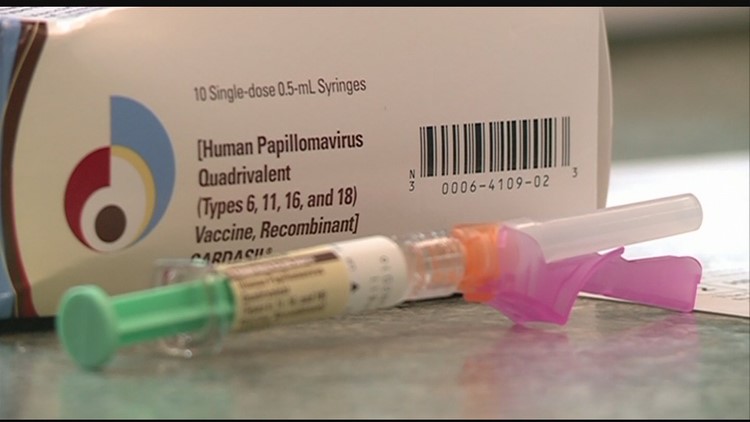

Unlike a traditional pap smear, which is inspected under a microscope to detect abnormal cells, an HPV test is run through a machine that detects the virus’ presence from its DNA. This study is the first to do a head-to-head comparison between the two detection methods.

“The important thing is that we detected more pre-cancers earlier [with the HPV test],” said Dr. Gina Ogilvie, a professor at the University of British Columbia and the lead investigator of the study. “But also, when women had a negative HPV test, they had more reassurance that they truly would not develop pre-cancer in the next four years.”

This reassurance is twofold. Since cervical cancer is caused by HPV, a negative screen for the infection means a woman is unlikely to develop pre-cancers. And since the HPV test is molecular, rather than relying on human interpretation, it is less likely to provide false negatives. At the end of the trial, patients were tested using both detection methods. Twenty-five cases of pre-cancer were found by the HPV test in women who had normal pap smears.

“This study was designed to inform health agencies, health authorities, and cancer agencies about screening,” said Ogilvie. “We're hoping they'll use this information and say, ‘Okay, what kind of recommendations do we want to make for women for cervical cancer screening?’”

To Ogilvie, the answer is clear: primary HPV testing provides more accurate results and more confidence in diagnoses. She hopes that guidelines in the United States and Canada will begin recommending HPV testing as the primary screen for cervical cancer in women over 30.

For Rachel Winer, the research is exciting for another reason. "You can look at the incremental benefit of different types of strategies among women who are coming in for screening, but the reality is that most cervical cancers are diagnosed in women who have either never been screened for cervical cancer or are not compliant with recommended screening intervals.”

Winer hopes this study will pave the way for women to test themselves at home — no doctor’s appointment required. Women would collect their own sample and mail it to a doctor or a lab for analysis. Allowing for at-home testing could help single mothers and people in underserved communities access a procedure that’s critical for women’s health.

“It opens up the door for HPV self-sampling strategies in the US,” said Winer. “[It has] the potential to reach hard-to-reach women.”