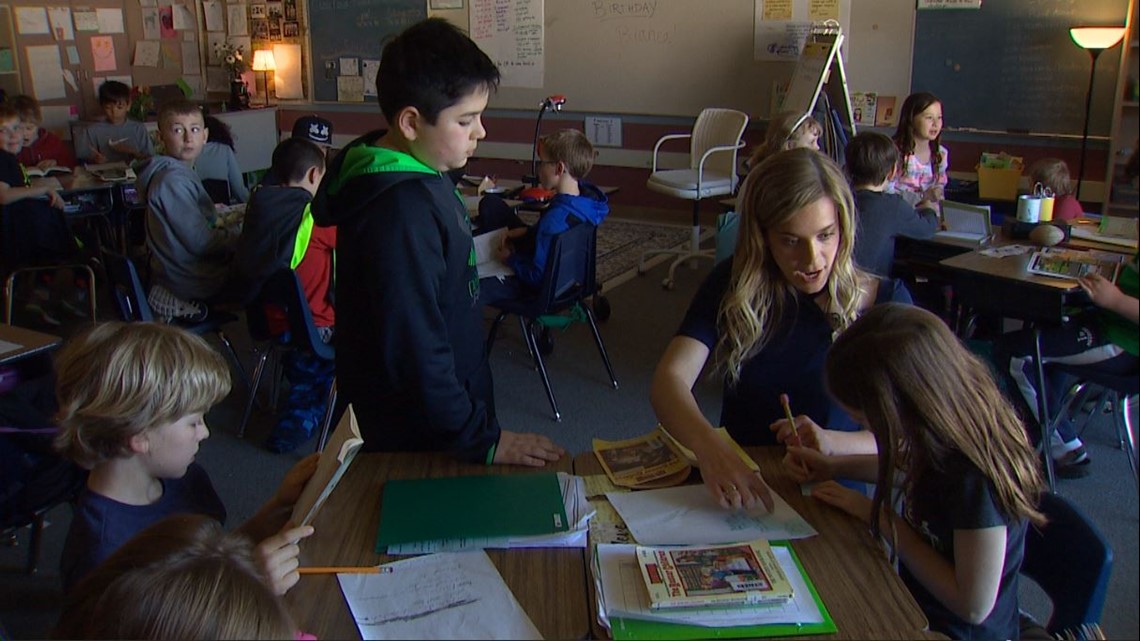

Oregon school district includes all students with disabilities in regular classes

It doesn't matter if the students in this school district have Down syndrome, autism, severe dyslexia or ADHD. They're all simply part of the crowd.

Mirfendereski, Taylor

Editor's Note: If you are viewing this story in our mobile app, click this link for more photos and video.

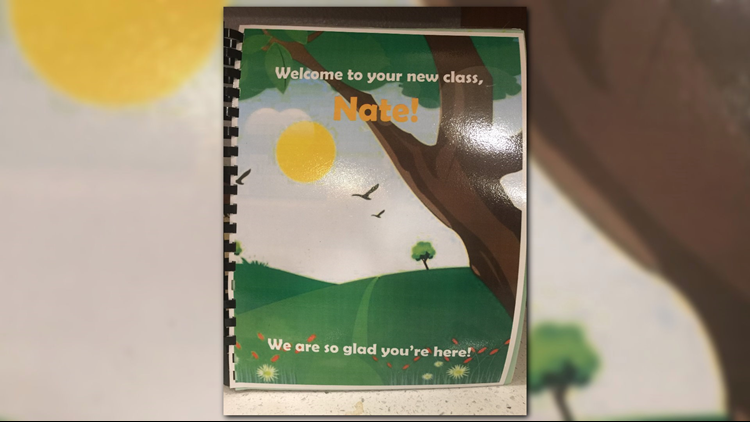

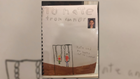

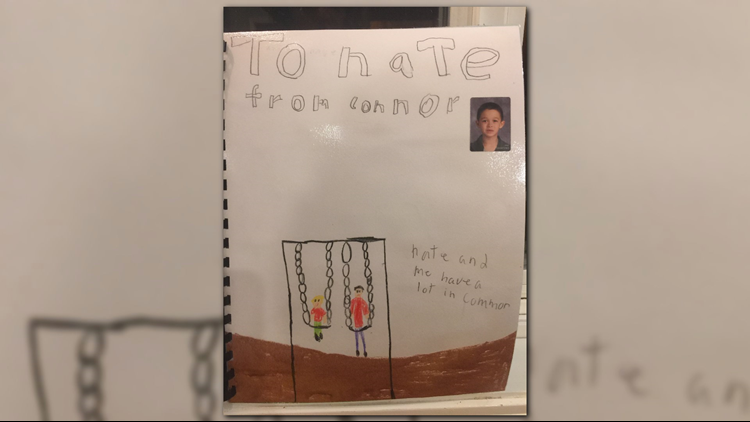

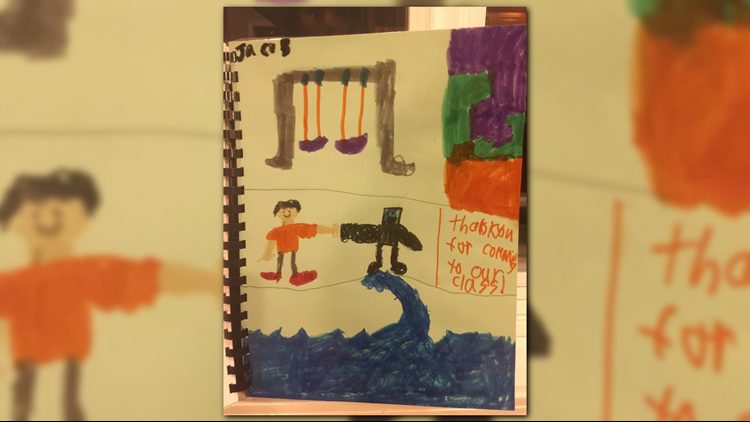

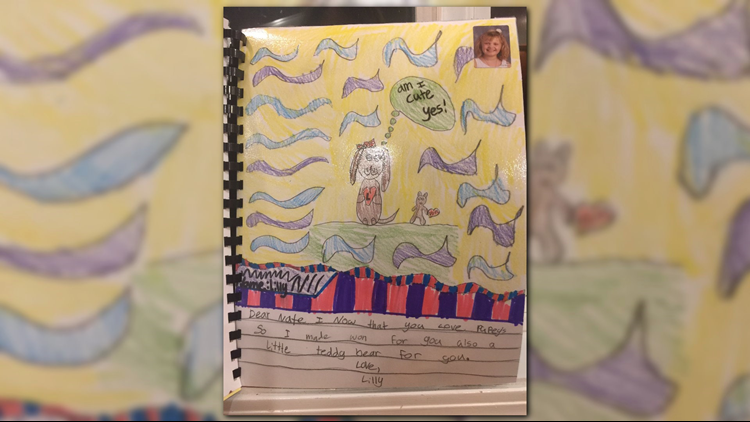

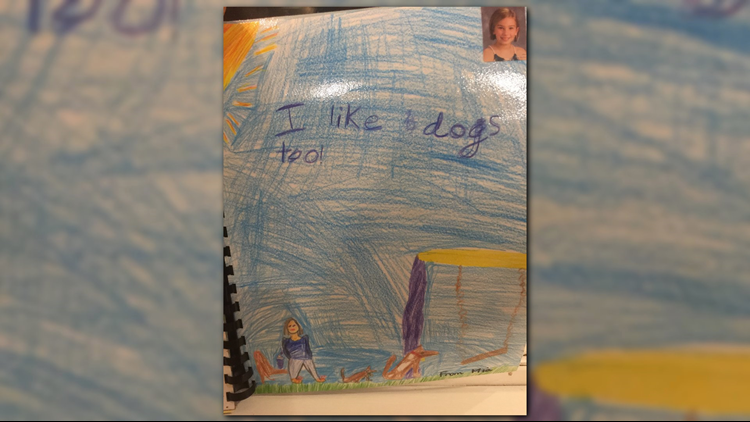

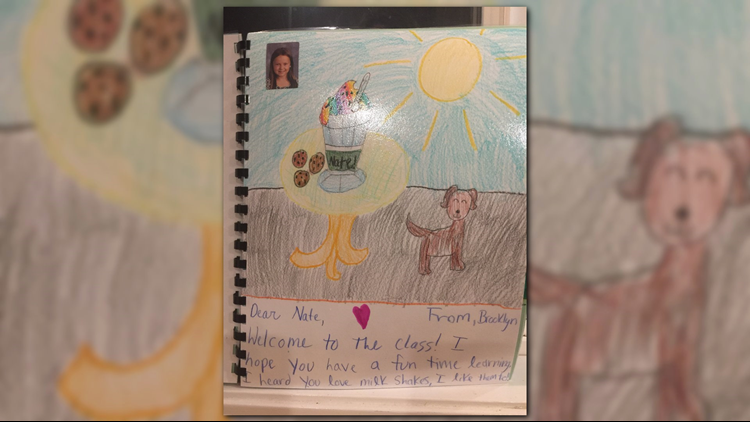

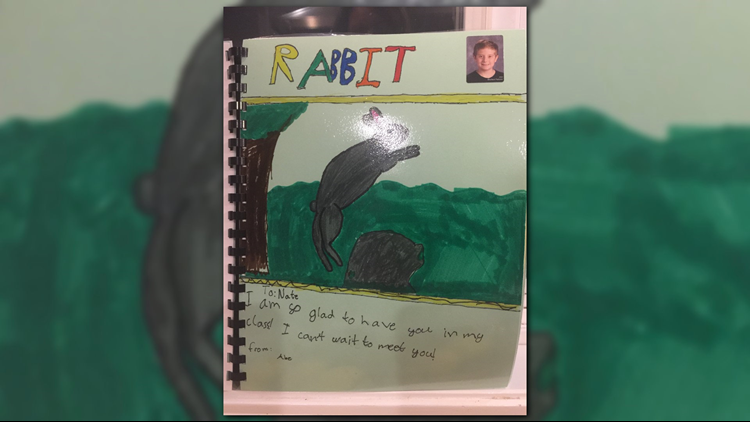

A Homemade Book

WEST LINN, Oregon — Danielle Paskins braced herself each day she opened 9-year-old Nate’s black backpack after school.

The daily progress report waiting inside broke down her son's day. How many times did he go to the bathroom? What did he eat for lunch? What activities did he accomplish? How did he interact with the other kids in school?

It was only a matter of time, she worried, that she’d find a note from the teacher saying Nate’s unexpected outbursts disrupted the rest of the kids in the third-grade class. It’s why Paskins didn’t want the Oregon school district to place her non-verbal son, who has Down syndrome and autism, in a typical classroom with students who don't have disabilities.

"What if my child is taking away from the education of all the other kids?” Paskins said. "I was imagining he was at school crying and being hushed all day.”

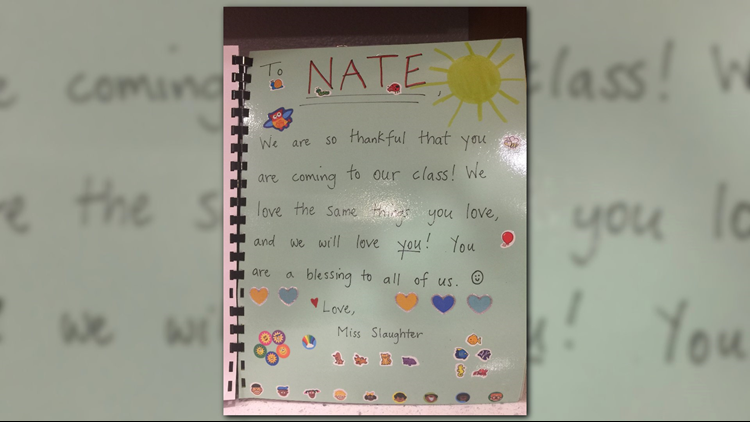

In this mother's mind, inclusion was the worst option for her son. But by March 2018, the note the mother feared never came. Instead of a progress report, Paskins pulled out a homemade 30-page book one day, with a letter from Nate’s new teacher and laminated drawings from his non-disabled peers in the Stafford Primary School class.

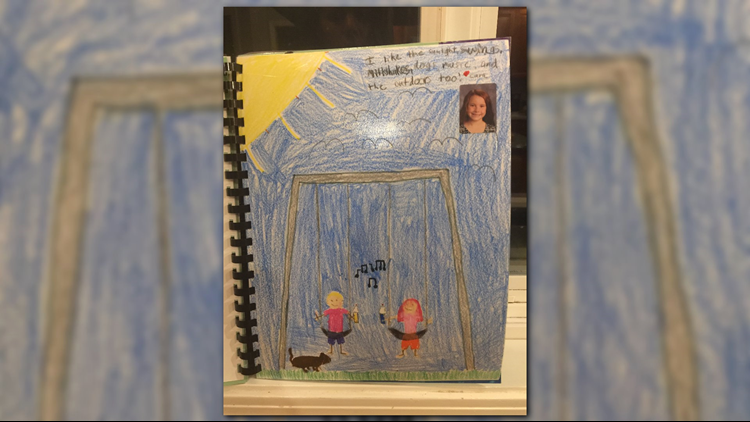

Nate’s classmates wrote and drew pictures about their shared love for dogs, swinging on the playground and drinking shakes — the only way 40-pound Nate can consume food. They highlighted the things they had in common with their new classmate who — until that moment — always stood out as different.

“We are so thankful that you are coming to our class!” wrote Nate’s teacher, Amy Slaughter. "We love the same things you love, and we will love you! You are a blessing to all of us!”

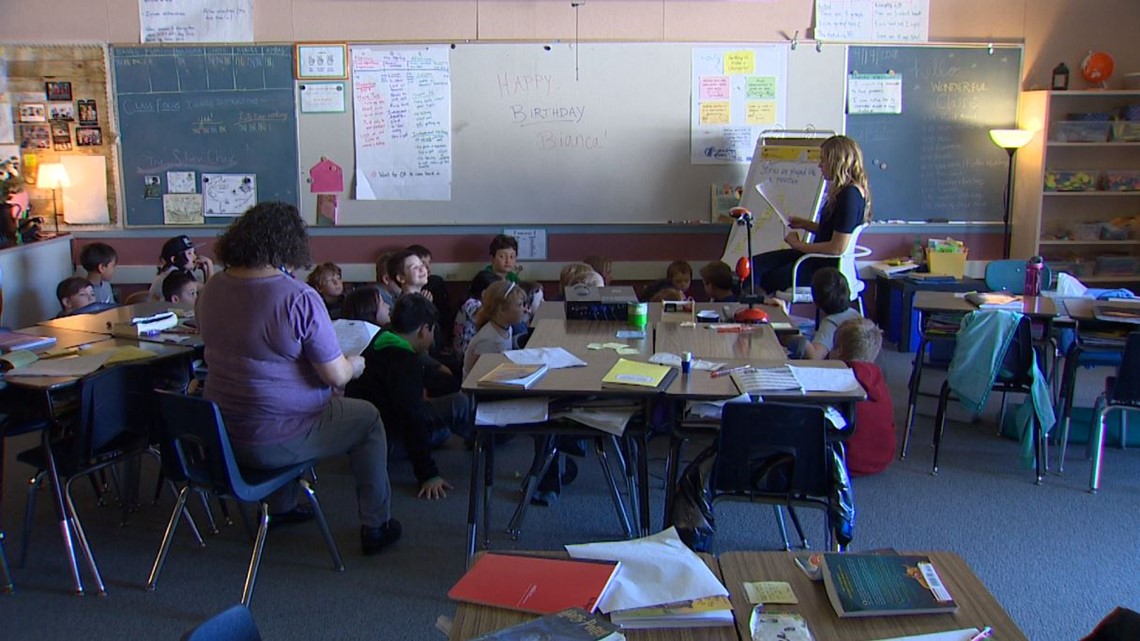

It's a culture embraced by all school employees — from the superintendent to the teaching assistants at the West Linn-Wilsonville School District, about 15 miles south of Portland. It doesn’t matter if the students in this school district have Down syndrome, autism, severe dyslexia or ADHD. They’re all simply part of the crowd.

Before 2012, the district bussed its special education students to segregated, self-contained classrooms — often in schools outside of their own neighborhoods. Today, Nate Paskins and every other special education student in the district spends the majority of the school day learning in a regular classroom around students who don’t have special needs.

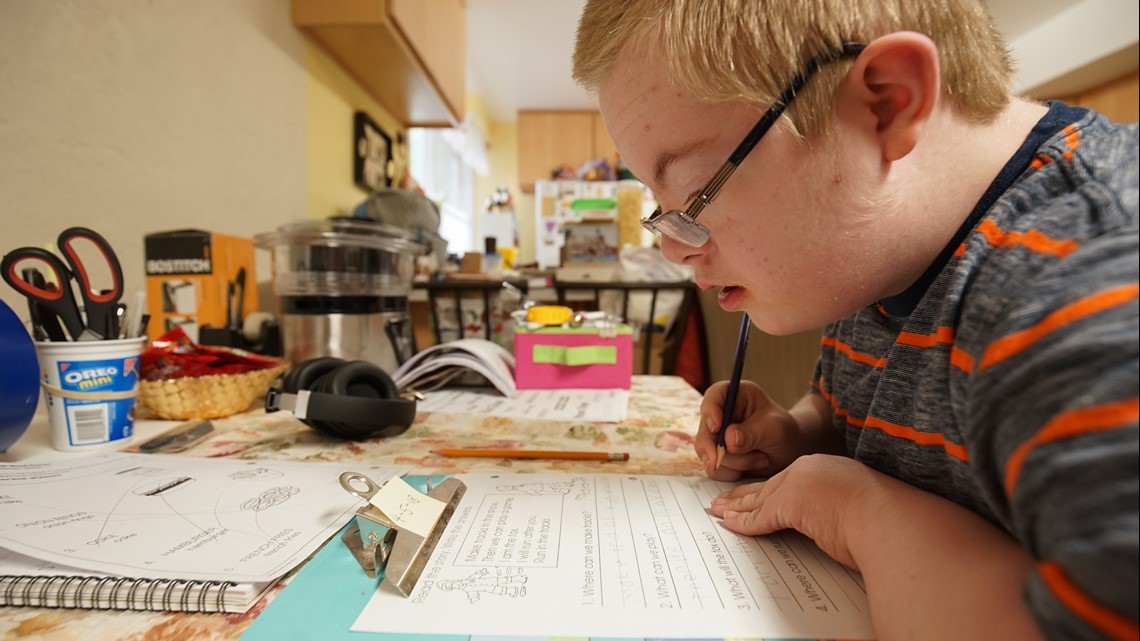

Even though every student who has a disability in this district spends time in a regular class, they each receive individualized support as needed — from one-on-one teaching assistants, specialists and therapists to modifications to the curriculum. Nate, who only comprehends basic, one-step commands, has a full-time, one-on-one aide. But his most valuable lessons come from the classroom peers who look after him every school day.

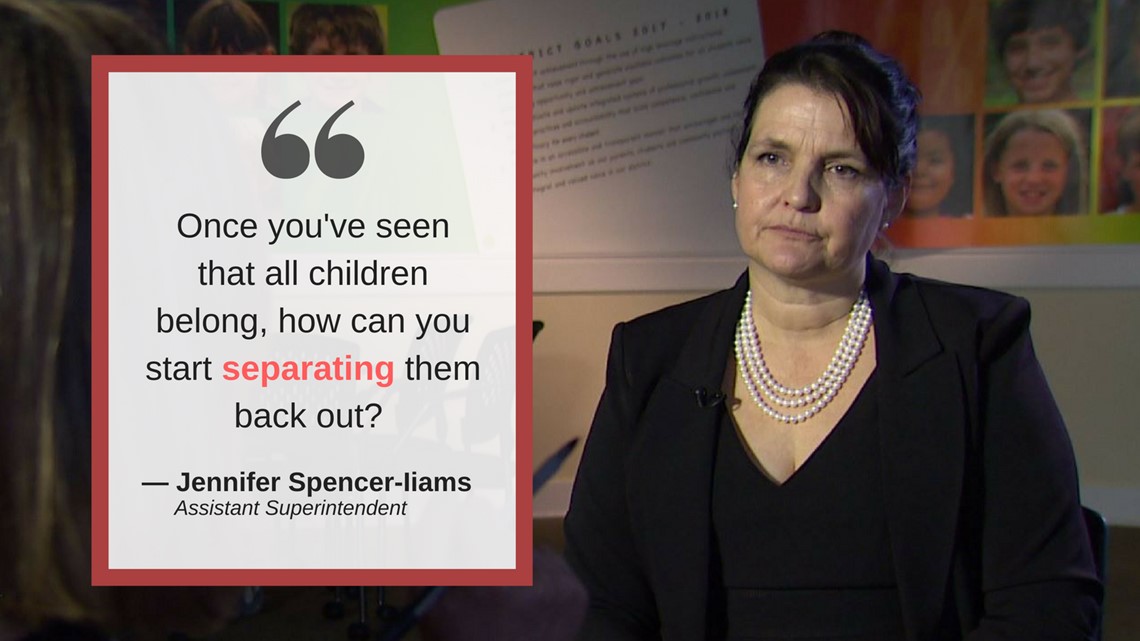

“Students — no matter what their learning style or why they’re receiving special education — they need to feel like they belong with their peers,” said Jennifer Spencer-Iiams, the district’s assistant superintendent. "They need to feel a part of the work. They need to be engaged and challenged. All students.”

A Far Cry From Washington

Schools across the Pacific Northwest and the country include special education students in general education settings to varying degrees. But a model like this is rare, even in Oregon. Experts say the West Linn-Wilsonville School District, which serves nearly 10,000 students, is one of the few to include 100 percent of its special needs students in every class.

"(The students with disabilities) are definitely a part of the social network. They have friends. They are missed when they are not there, and they are actively participating in all of the different curriculums,” said Tandy Wolf, a learning specialist at Cedar Oak Park Primary in the district.

The district’s inclusion model is a far cry from the way many schools do business in the state of Washington, where thousands of kids are often denied their legal right to learn in regular classrooms. A KING 5 investigation found that Washington schools exclude students with disabilities from general education settings more often than schools in nearly every other state in the country.

That’s not supposed to happen under state and federal law. Public schools in the United States are required to provide specialized educational services to all children with a disability recognized under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

That law guarantees that the more than 150,000 special education students in Washington have a right to go to school in the “least restrictive environment.” It means they should get the opportunity — to the maximum extent appropriate — to learn in a general education setting around children who are not disabled, even if they can’t keep up academically or if schools have to modify the way the children learn with extra support.

RELATED: Sam Clayton's Story

Just over half of Washington's 6 to 21-year-olds with disabilities spend 80 percent or more of their day in general education classes. Only seven states have a lower percentage of special education students in regular classes, according to an analysis of the U.S. Department of Education's most recent IDEA report to Congress published in 2017.

Five percent of Washington's students with intellectual disabilities spend the majority of their day in regular classrooms. Only two states in the country — Nevada and Illinois — have worse inclusion rates than Washington in that category, according to the same report.

Washington's poor inclusion rates stem from an underfunded state special education system that leaves students with disabilities in limbo and school districts scrambling to comply with the law, according to experts. But it also comes down to a cultural shift that some superintendents and principals refuse to embrace.

"It's not unimaginable to me that all our historic practice of exclusion and isolating and creating resource rooms...has been a persistent thing that's hung with us,” said Chris Reykdal, superintendent of the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. "The entire science of learning has changed about that, and we are a state that's going to have to work a lot harder than others."

It Started With A Post-It Note

Creating a culture of full inclusion in West Linn-Wilsonville schools wasn’t an overnight switch, and district staff say it’s still not an easy one—six years after the journey started.

"It is complicated work, and it takes a long time," Spencer-Iiams, the assistant superintendent, said. "It's not a black and white situation, where today we're segregated and tomorrow we're inclusive."

Sometimes, teachers must work around the unexpected challenges that arise due to different student needs.

“It’s been simultaneously awesome and really hard,” Spencer-Iiams said. “There are challenges and things we have to keep working with but once you’ve seen that all children belong, how can you start separating them back out?"

In situations where a student’s behavior is disruptive, Spencer-Iiams said the general education teacher will move the class to a different spot while the aides and other support staff assist the special education student with his or her needs.

But over time, she said, the inclusive classrooms have normalized unexpected sounds and behaviors. That means most students can keep on learning without skipping a beat.

"There are moments that it can be distracting and we work through those, but that’s also kind of life,” she said.

It was Spencer-Iiams who woke up one day in 2012 with the goal to change the practice of segregating kids at the district’s 16 schools.

The 51-year-old, who oversees the district’s special education program, had spent years studying inclusion science. She knew the research proved students with disabilities do better when they’re placed in inclusive classrooms. And she knew the district needed to make a change the moment she tearfully told a mother that the district couldn’t accommodate her special needs child’s right to learn in a regular class.

Spencer-Iiams jotted down her goal on a post-it note: “100 percent inclusion.” Then, district staff started to make change through small steps that didn't cost a dime.

Long before the district shut down self-contained classrooms, general education teachers began to think of the students with disabilities as part of their class — instead of visitors. The teachers started to add the students to their attendance rosters so they could see their names every day, even when the students spent just 20 or 30 minutes in the classroom with the "typical" learners.

Spencer-Iiams said the district re-assigned teachers and specialists to different school buildings. It changed teaching titles and roles. Special education teachers, for example, became "learning specialists." The district also changed the focus of its professional development training so general education teachers could gain skills to support students with special needs.

Gradually, the district added more employees. Spencer-Iiams said they needed extra staff because the district grew larger, but also to better support special education students in general education settings.

"It certainly didn't cost less, and it likely has cost us a little bit more," said Spencer-Iiams, adding that she could not pinpoint how much it cost to hire staff for the district's inclusion efforts alone.

"But when it's the right thing to do for kids and it's more effective in terms of learning outcomes, how can you not?" she said.

In the 2015-2016 school year — after three years of beefing up staff, re-allocating resources and re-focusing training— the goal on Spencer-Iiams' single post-it note became a reality.

Not only did classes in the West Linn-Wilsonville School District change to include students with special needs, but the mindset among the thousands of educators — and most importantly, the non-disabled students in the Clackamas County schools — changed too.

“They are now at this point where they have grown up with them, and they are truly their classmates and their friends. They don’t think, ‘Oh, so and so has a disability,'” said Wolf, the elementary school learning specialist. “When they are in charge and they have a job, they are going to feel fine about hiring people with differences or doing something with a person who has differences. For them, it’s going to be typical.”

Aubree Schrandt, a senior at West-Linn High School who does not have a disability, said she never met a person with a disability before entering high school.

Taking classes with special education students has changed her perspective about people who are different than her, she said. It's also led her to develop solid friendships with the students who have disabilities in her class.

"It's definitely opened up my eyes and made me realize that these kids are just so amazing," she said, adding that the district's full inclusion model has not negatively affected her own academic progress. "These kids work twice as hard, and they're role models to a lot of people. You would never think of that if you don't build a relationship with them."

Spencer-Iiams, the administrator, acknowledges that not every student is going to perform the same in a general education setting. She said the district still determines the best course of action for a student based on his or her individual needs, as determined by the Individualized Education Plan — the legally binding document that helps students with disabilities achieve general education goals.

“Our inclusive work is not one-size-fits-all,” she said. “It’s one-size-fits-all in the sense that everyone is at their (neighborhood) school, but we still have a range of supports.”

Graduation Rates Rise After District Embraces Inclusion

More students with disabilities graduated high school after the district changed its inclusion practices, according to district data. In 2014, 71 percent of the special education students received diplomas. In 2017, 79 percent graduated from high school.

Over the same time period, more students without disabilities graduated from the district, too. In 2014, 88 percent of the entire student body graduated from the district. In 2017, that number rose to 93 percent, according to the same data.

But there are other significant benefits of inclusion that the graduation rates don’t show.

Spencer-Iiams said district staff now have higher academic expectations for their students with disabilities after exposing them to a more rigorous curriculum in the general education setting. Before, she said, they underestimated what the students could accomplish due to communication challenges associated with their disabilities.

“Just because these kids couldn’t express it to us on a multiple choice test or in a five-paragraph essay doesn’t mean they can’t be learning the content at least in some way, shape or form,” she said. "Why do we assume just because we haven’t figured out how to connect to their learning style that they are not learning?”

Spencer-Iiams said she hopes administrators in school districts that are still segregating their students with disabilities will consider becoming more inclusive, like the West Linn-Wilsonville School District. It doesn't have to break the bank, she said.

"They could immediately change how they do attendance. They could change how they talk about children. They could change their expectations for learning," she said. "Money is a reality in education, and it's an important factor, but there are (inexpensive) things we can do to get us in a place to be more inclusive.

'A Sense Of Belonging'

For Danielle Paskins, all it took was that homemade book from Nate's third-grade teacher and classmates to change her mind conclusively about the benefit of including Nate with the other kids.

Flipping through the 30-pages in tears, the drawings gave her hope that her son could have a connection with children his own age — even though specialists had always warned her: Nate could never form a bond.

"A sense of belonging. Isn’t that what every kid wants?” said Paskins, the 45-year-old mother of three. "For these kids to be like, ‘He needs to belong,' How can we make him feel that sense of belonging? It’s really powerful.”

Photos: Third-Grade Students Create Book For Nate Paskins

Weeks later, she got a message from a mother of a student in Nate’s class. The 9-year-old got his first-ever invitation to have a play date with another kid.

"I don't think (the mother) realized in that moment of sending it, how powerful that would be for us as a family,” Paskins said. “(Her son) was just a sweet boy that wanted to reach out.”

Other kids have stepped up and befriended Nate, too. They compete for the chance to read to him in the third-grade class.

“They don’t get scared, and they don’t stop and stare and make a big deal,” said Hailey Alberts, Nate’s para-educator. "They just kind of go on like everyday life.”

Alberts said she’s watched Nate become more social over the weeks and months. He’s finally forming a bond with others few expected he could make.

Nate's mom said she’s seen simple but profound differences in his ability to follow directions at home.

“He had a really hard time with routines before he was in the typical classroom,” Paskins said, adding that her son now pays attention to and models his peers in the class.

This year, Nate learned how to hang up his backpack. He understands when it’s time to go somewhere. He knows to pick up his books when it’s time to read.

"It doesn't seem like a big deal but that's what we build on,” she said. “I wonder how much further along he could have been if he had not spent those three years in self-contained classrooms."

The small victories carry a lot of weight for this mother.

But her only real goal is for her son to fit in.

"We had to get to a place where we recognize we weren't giving up on our son. We were just accepting who he is,” she said. "That allowed us to settle into a place where we just want him to feel loved and a sense of belonging.”

Resources and Support

If Your Child Has A Learning Disability

Know your rights. The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction offers guidance for families, which includes a handbook with information about you and your child's rights under state and federal law.

If you have questions about the special education process or difficulties communicating with your school district and need additional help, OSPI has special education parent liaisons available to assist you.

The state also has education ombuds who work with families to answer questions and help resolve concerns. Contact their office online or by phone at 866-297-2597.

About This Series

This story is the third part of "Back Of The Class," a multi-part investigation into the state of special education in Washington. The series exposes the reasons why Washington lags behind much of the country in serving one of our most vulnerable populations: students with learning disabilities.

Contact The Reporters

Susannah Frame is the Chief Investigative Reporter at KING 5. Her stories have exposed many wrongs, leading to changes in public policy, congressional investigations, federal indictments and new state laws. Follow her on Twitter @SFrameK5 and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at sframe@king5.com.

Taylor Mirfendereski is a multimedia journalist, who focuses on in-depth reports and investigations for KING 5's digital platforms. Follow her on Twitter @TaylorMirf and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at tmirfendereski@king5.com.