Family members of Rod Jones, a former University of Washington tight end and NFL player who died by suicide Saturday, said they believe head trauma from football led to the 54 year old's downward spiral.

"People love the sport of football, but they don't realize the cost of the sport. I want to keep that conversation going," said Jamie Jones, his 24-year-old daughter. "My dad was struggling, and I want people to know that. He was hiding his depression."

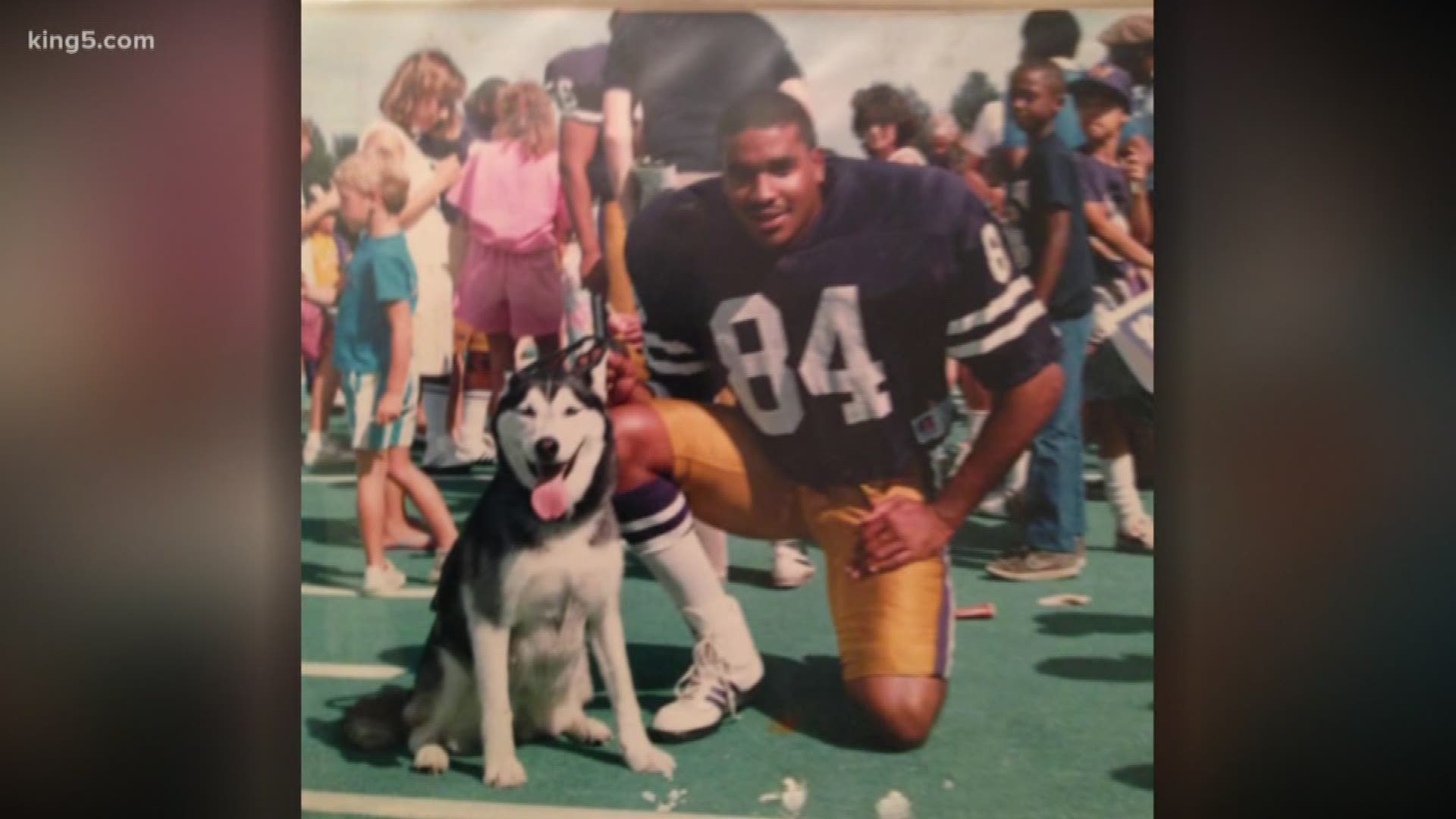

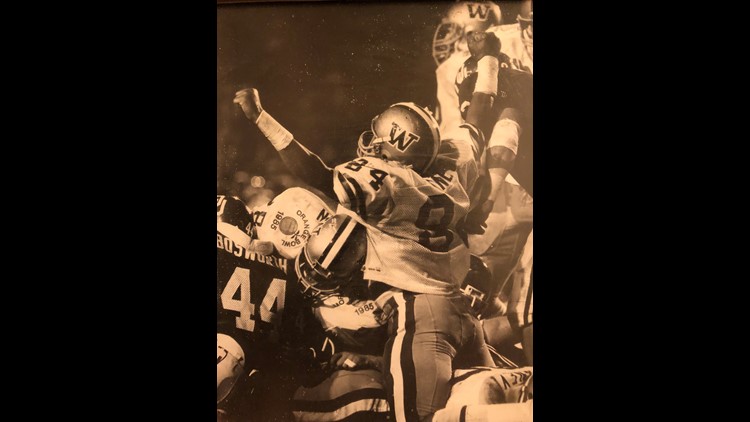

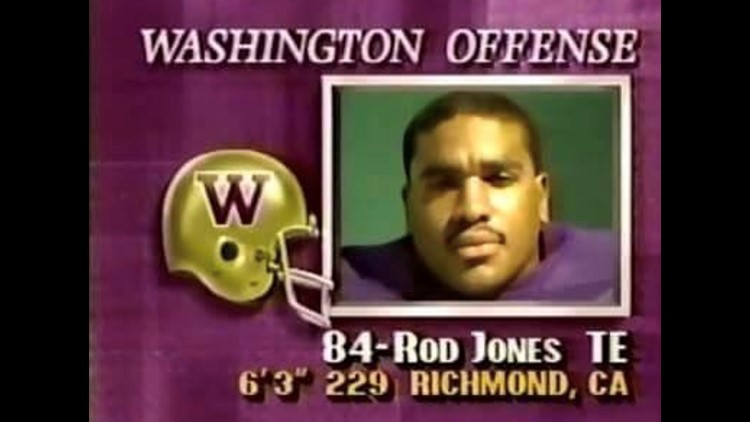

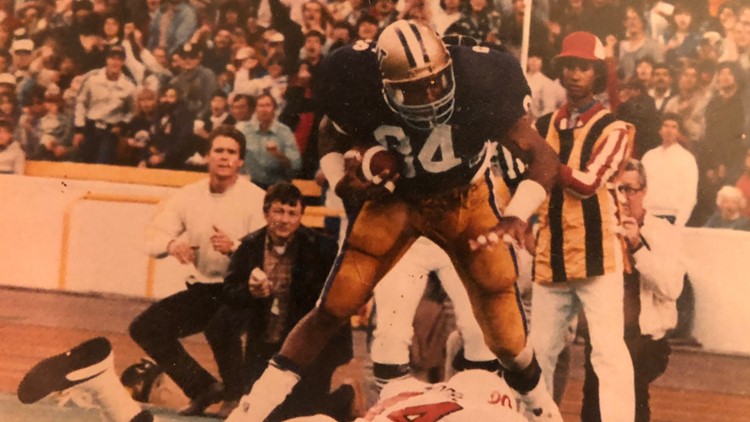

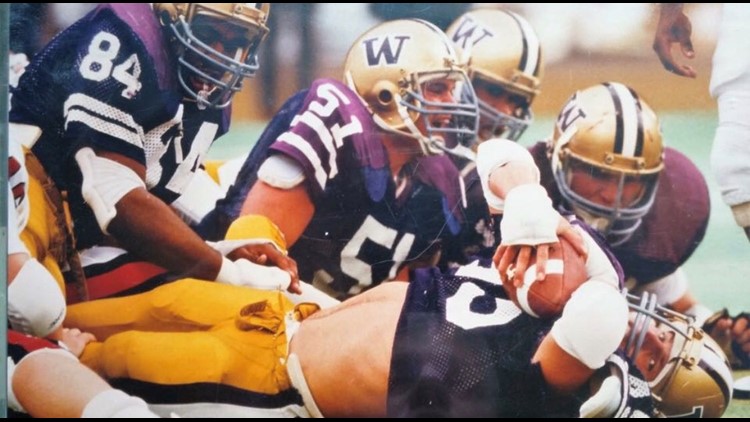

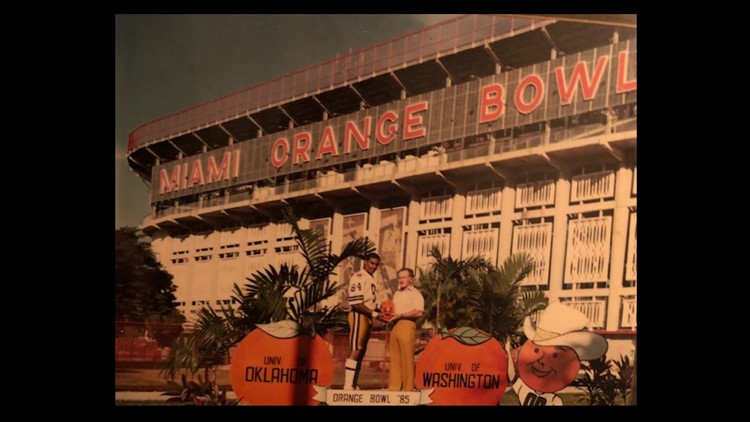

Jones played for the Huskies in the 1980s. His standout career included a 1985 Orange Bowl win. He later spent parts of three seasons in the NFL, where he played for the Kansas City Chiefs and the Seattle Seahawks. Most recently, Jones had been working in the UW athletic department as a popular academic coordinator — mentoring student athletes for the past 18 years.

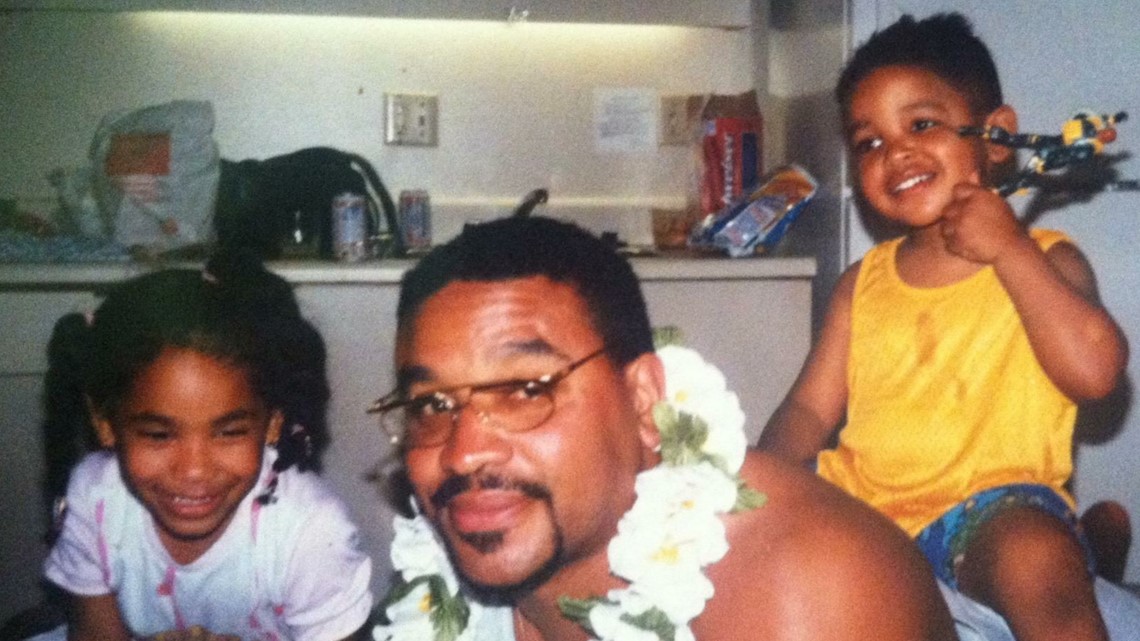

"I would want people to remember my dad as a big, loving teddy bear... He protected his boys—his students—like they were, like they were us," his daughter said. "We loved seeing that. He was a friend before he was a counselor or a mentor to anyone here. He was your uncle, your dad, your cousin. He was family first, and then entered your life as your mentor."

Doctors declared him dead Saturday afternoon at Harborview Medical Center, where his family members, friends and former teammates surrounded him during his final hours. He is survived by his wife, Carla Jones; son, Rod Jones, Jr.; daughters Krystal Roquemore and Jamie Jones; and granddaughter, Arielle Hatten.

"We always thought that he was going to be there forever until we had kids— until we got married. I thought he was going to walk me down the aisle and be an old man because that's what he wanted," Jamie Jones said. "But when the disease took over, it wasn't him anymore. That piece of him was gone."

Jones had recently been diagnosed with early-onset dementia, his daughter said, and he had a history of alcohol abuse. His wife and children said they believe he was suffering from symptoms of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a brain disease found in athletes, military veterans and others with a history of repetitive brain trauma. The symptoms include mood swings, memory loss, depression and aggression.

Currently, the disease can only be detected with a dissection of the brain after death, so it's unknown if the former football star had the disease.

"There's no question that when you have CTE — when it progresses — it can completely change your personality," said Chris Nowinski, CEO of the Concussion Legacy Foundation. "If you talk to wives of people with late-stage CTE, when it comes to impulsiveness, when it comes with aggression, when it comes with paranoia, some expressed that they were scared to live with their loved one. This isn't a dementia where you grow quietly into the night. This can be incredibly rough on families."

Jones' Brain Donated For Research

Rod Jones' family said they donated his brain to Boston University's CTE Center, where about 30 scientists are now analyzing hundreds of athletes' and veterans' brains to determine whether or not CTE is present and to better understand the disease.

"My reason for (speaking out) and my donation (of his brain) is because secrets don't get fixed. Dirty laundry doesn't get cleaned when it's hidden," said his wife and partner of 32 years, Carla Jones. "Donating his brain is going to help future athletes and future little leaguers. The only way it can be fixed is if we share him."

Rod Jones As A Huskies Tight End

In addition to analyzing athletes' brains, CTE Center researchers spend months conducting interviews with surviving family members and reviewing medical records to better understand donors' symptoms and experiences while alive. The goal of the research, Nowinski said, is to find discoveries that would allow an early diagnosis of CTE – and possibly even treat it.

"Studying football players is important because football players have taken thousands of blows to the head. There is a correlation between number of years from playing football and CTE," said Nowinski, who co-founded the CTE Center. "From my perspective...we do need to radically change the game if we consider that it's destroying the brains of people who play."

Nowinski said it's likely that people who develop CTE have a higher risk of suicide due to the concussions they suffer, but researchers don't yet know if the disease itself is increasing the risk of suicide.

A Different Person

Many of Jones' co-workers, friends and former teammates said they were shocked to learn of the struggles he carried behind his contagious smile. But his close family members say they watched Jones' personality become unrecognizable in the last few years.

"I saw a decline," Carla Jones said. "He was changing and morphing into something that was so irrational, so scared, so loss-of-control. The last six months have been noticeably scary for me here at home."

Jones' family members say he became increasingly forgetful. His children, Jamie and Rod Jr. say their father had trouble remembering names, and he'd regularly misplace his wallet and keys.

"He was well aware of what was going on. He would say, 'Man, if I didn't have all these concussions, my memory would be there.' He would just complain about concussions, concussions, concussions all the time," Jamie Jones said.

His daughter said her dad started to become easily agitated, and he'd have intense mood swings without warning.

"He would lash out on me and my brother and my mom randomly, and anything could trigger him," Jamie Jones said. "The next day, when we'd try to confront him about it, he would forget it even happened."

Carla Jones said her husband's depression continued to worsen. She said he quit driving to work almost two years ago because he would experience panic attacks in traffic.

"I want people to know that he was a gentle giant when he was himself. He loved everybody," his wife said. "He was hiding things from everybody until he couldn't hide it anymore."

Desperate For Help

Carla Jones said she and her husband sought out the help of doctors, including a Portland-based neurologist, for answers about Rod's symptoms.

She added that he joined an NFL concussion lawsuit, seeking damages for his head trauma during his football career.

"He said he got hit so many times (during football), that he didn't know who he was at times." she said. "He said he saw stars."

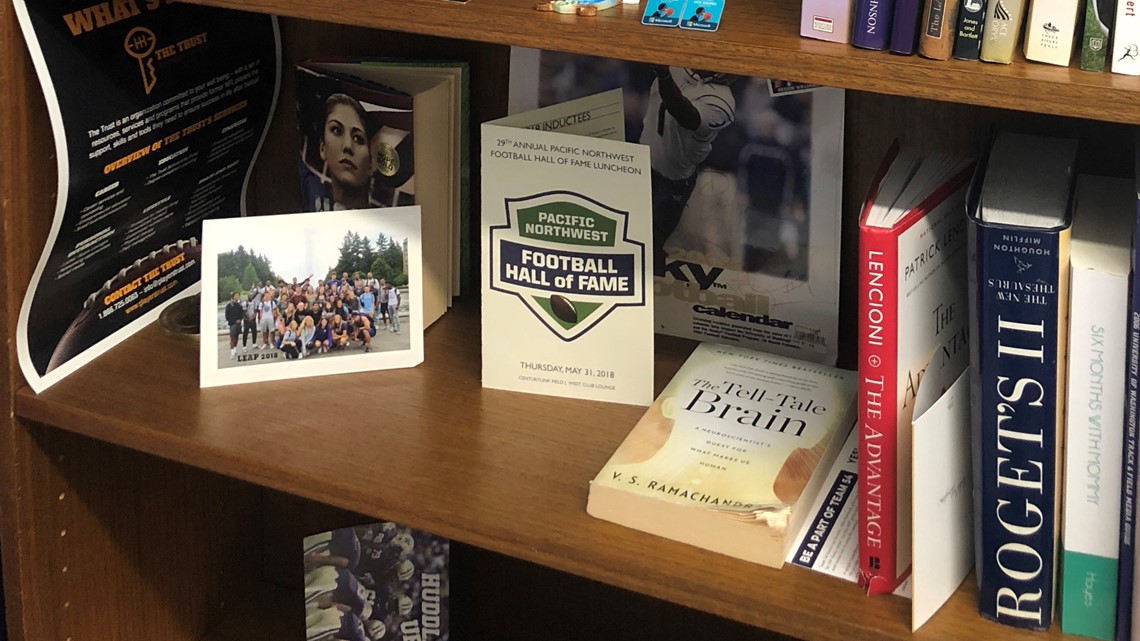

On Monday, Jamie Jones began cleaning out her father's University of Washington office.

As she packed up shelves of his football memorabilia, she found a book: The Tell-Tale Brain.

"It just struck me," she said. "He just wanted so badly to know what was happening with himself."

A memorial service is planned for this Saturday at the Don James Center at Husky Stadium.

"He loved so hard and was so passionate about what he did. Football is what he did," said his 24-year-old son, Rod Jones, Jr. "I just want people to remember what a great person he was."