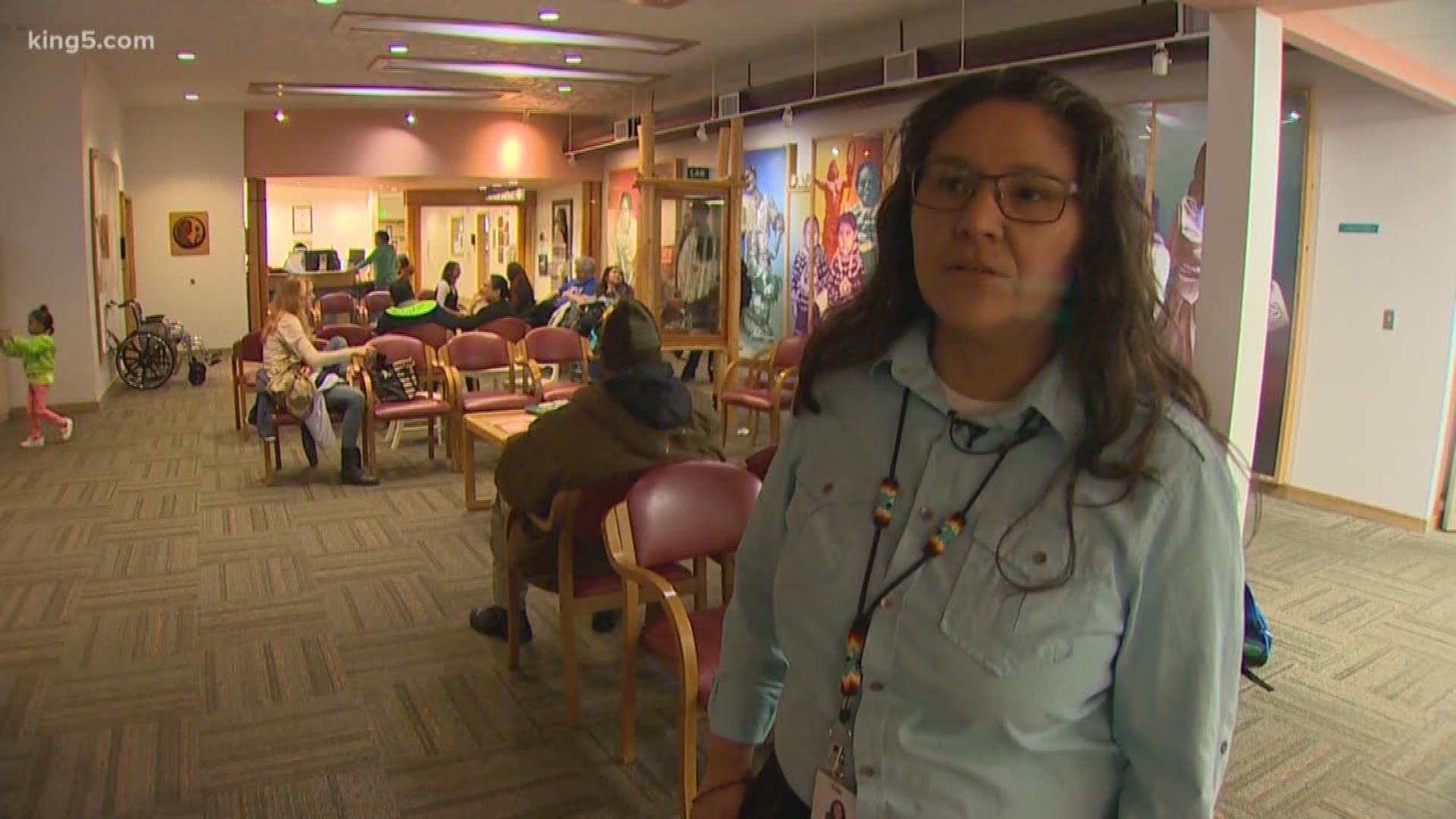

A Seattle clinic that primarily serves indigenous peoples is scaling back services because of the ongoing government shutdown.

The Seattle Indian Health Board clinic serves about 6,000 people each year – 70 percent of them are American Indian or Alaskan Native, according to the nonprofit’s CEO Esther Lucero.

“So we serve everybody, but our motto is we serve everybody in the Native way,” she said.

Lucero said they usually receive federal funding through the Department of Interior. Without that, they’ve lost 25 percent of their operating budget.

“So now we’re in day 34 of the shutdown, which means we’re dipping pretty significantly into our reserves,” she said.

To date, no employees at the clinic have been furloughed. But the clinic had to stop providing services on Saturdays during the shutdown. Lucero worried this could cause problems of access for working parents and families.

Louisa Olebar said the clinic’s impact on the native community is significant.

“I’m thankful it’s here, because I can’t afford other places,” said Olebar. “Because I don’t have any medical right now. And I come here, and I have friends, relatives. Being an elder I can go downstairs and have lunch, do some crafting.”

“I’d be sick or I wouldn’t be around,” she said. “They’ve helped me a lot.”

It's not the only shutdown impact on native peoples. Last week, Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA) visited the Port Gamble S'Klallam tribe, which told her their clinic's only full-time doctor is currently working without pay.

Lucero hoped for a quick resolution to the shutdown – as the potential impacts mount.

On Feb. 8, the clinic would be forced to begin furloughing staff. Lucero said staff are beginning to feel the pressure. Approximately 50 of the 180 staff members would be vulnerable to cuts.

The Indian Health Board also runs an inpatient addiction treatment facility in Renton, called Thunderbird. Lucero said if the shutdown continues into next week, they’ll also be forced to close 36 of the 65 beds there.

“Without having traditional Indian medicine as a component of their treatment, it can greatly disrupt their recovery,” she said. “Or the movement towards sobriety.”

One bright spot – she said Planned Parenthood gave the clinic a grant that allows them to continue a program for elders up to 15 weeks. She said 40 percent of the elders in the program experience homelessness.

“As an urban Indian health program, we rose from the social justice movements that were initiated by these people,” she said. “So the idea to not be able to provide the service – means that I’m doing the community an injustice.”

Lucero said this shutdown impact is especially frustrating because native people are guaranteed access to healthcare under treaties with the government.

“I would say there’s no border wall worth harming our people,” she said. “Going back on a promise that predates any of this administration that comes from treaty rights. I would say remember, we have people’s lives at stake. And we are all part of fulfilling this promise.”

“Why do we have to pay for someone else’s mistake?” asked Olebar.