SEATTLE — Editor's note: The above video on police faking radio communications during the protests in the summer of 2020 originally aired in January 2022.

The Office of Inspector General released a report Wednesday identifying critical errors by the City of Seattle and Seattle Police Department leading up to and during the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest (CHOP).

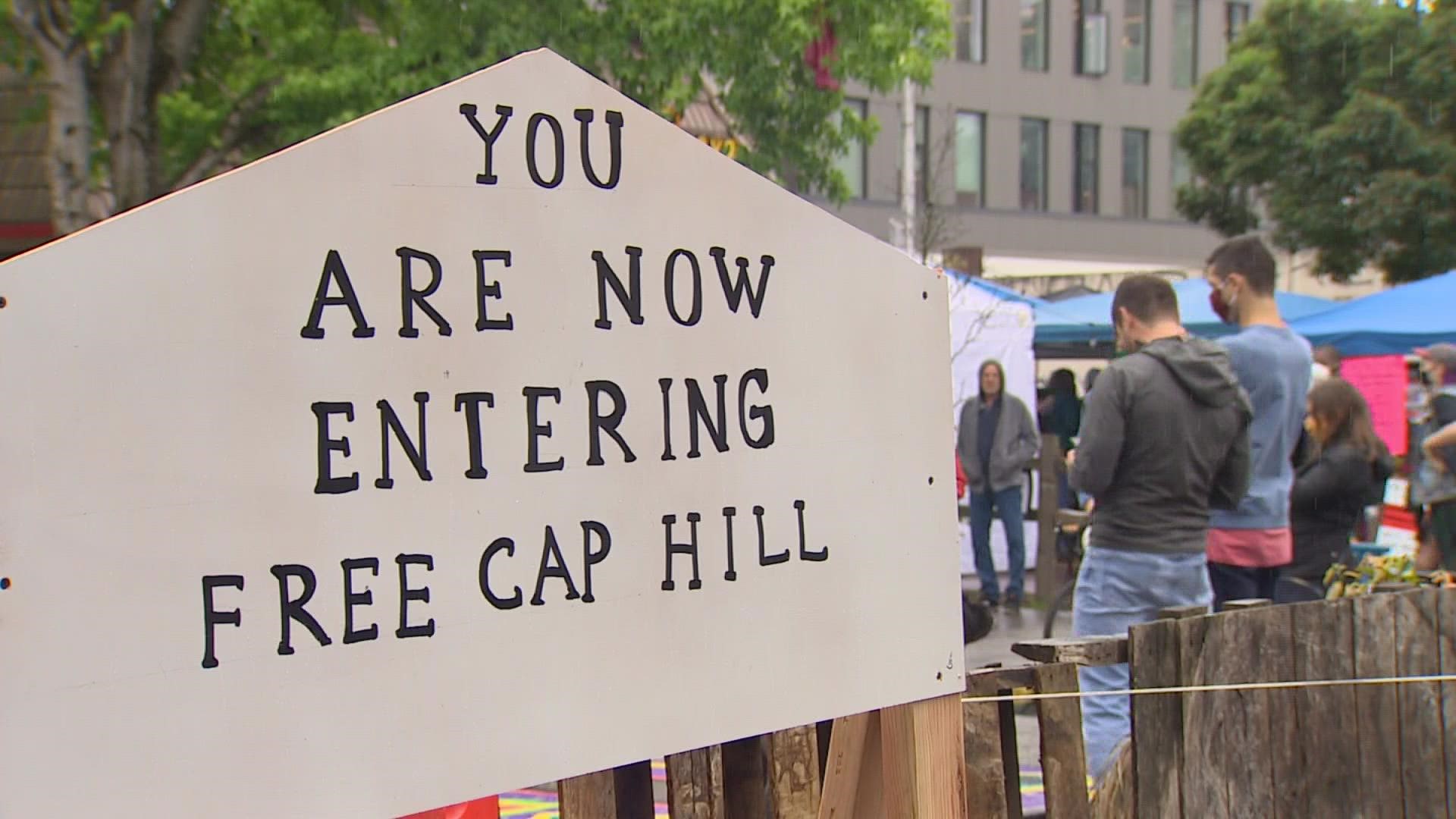

The 81-page report is the result of a Sentinel Event Review in which a panel of community members and SPD representatives identified decisions made and actions taken by the city and SPD. Some of those decisions "eroded public trust" and led to "poor policing outcomes" between June 8, when CHOP was formed in Capitol Hill, and July 1, when former Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan ordered the police department to disband the occupied protest.

The protests followed the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

The report began by analyzing the city's "unprecedented" decision to evacuate the East Precinct based on intelligence from the FBI that protesters planned to target government buildings and also in the hopes of de-escalating tensions between police and protestors. SPD evacuated the precinct on June 8. SPD was supposed to return to the precinct the next day, but it remained empty for the next 23 days.

The move led to complaints that SPD's evacuation from the precinct resulted in the establishment of CHOP, which has been criticized for criminal activity. The zone experienced four shootings in 10 days, which resulted in the deaths of two teens.

The report cited a lack of accountability, leadership and communication by the city and SPD that characterized the withdrawal from the East Precinct. Both Durkan and former Seattle Police Chief Carmen Best deny giving orders for SPD to evacuate the precinct and there's no documentation identifying who was involved in meetings discussing the withdrawal. A lack of clear communication between the city and SPD and within the police department itself led to confusion within the ranks and escalated concerns within the community that the situation was out of control and lacked clear leadership, according to the report.

The report also reviewed two instances where SPD deceived or misled the community during the occupied protest.

A ruse by Seattle police

In the first instance, SPD officers faked radio chatter that members of the Proud Boys were marching around downtown Seattle, some possibly carrying guns, and heading to confront protesters on Capitol Hill.

The Proud Boys is a far-right extremist group with a reputation for street violence.

A lieutenant with the Seattle Police Operations Center told Seattle's Office of Police Accountability the radio communications may have been made to test "the response of individuals who the department believed was monitoring its communication channels." According to the Office of Police Accountability investigation findings, an SPD Captain appointed an officer to recruit a team to fake the radio traffic to draw protestors away from the East Precinct.

The review found the ruse was "an intentional manipulation of protestor fear of a violent white supremacist group" in an attempt to undermine Black Lives Matter protests at the height of anti-police tensions. Panelists said the incident was indicative of structural and internalized racism in police decision-making.

The report found the ruse inflamed tensions in the occupied protest, as many found it reasonable to believe a white supremacist group could be marching to confront protesters.

The fact that the radio transmissions were not recorded and stored according to SPD guidelines caused many panelists to believe the officers were acting in "bad faith."

The report found SPD failed by not having clear policies related to being dishonest when communicating with the public. A lack of communication about the ruse led some other officers to believe armed Proud Boys were marching through downtown Seattle. Furthermore, the report found the Captain who authorized the ruse did not effectively supervise the officers broadcasting the disinformation over radio transmission.

Misleading statements

The report went on to analyze a June 10 press conference where several misleading statements were made by SPD and later repeated in a video message from former police chief Best to officers. A spokesperson said there were credible threats to burn down the East Precinct, which would endanger adjoining residences and apartment buildings.

SPD also made claims that protesters were setting up armed checkpoints, asking for identification to enter the CHOP zone and extorting money from citizens and businesses in order to operate within the protest area.

The report questioned the legitimacy of threats against the East Precinct and claims that armed guards were requiring ID for entry into the protest zone. Reports from witnesses indicated there were armed protesters but they were not stopping anyone from accessing the CHOP zone or asking for identification.

The claim that protesters were extorting money from business owners and residents was made in the comment section of a local blog and also to a business owner who shared that experience with the panel. However the person who claimed they were extorted declined to speak with the panel or follow up with journalists about their experience. Panelists found SPD damaged its credibility by repeating the story without verifying whether or not it was true.

Panelists were concerned SPD purposefully attempted to portray the occupied protest in a negative light with its statements. SPD's inability to substantiate claims of intimidation or extortion within the occupied protest zone was also seen as a failure of communication between the department and residents and business owners living inside CHOP.

Cut off from safety services

The report goes on to analyze the city and the police department's failure to communicate with residents and business owners inside the protest zone, who were cut off from city and public safety services, as well as ineffective communication between city departments surrounding two fatal shootings in the protest zone.

The first shooting occurred on June 20. Around 2:18 a.m., an argument broke out on Cal Anderson playfield and 19-year-old Horace Lorenzo Anderson was shot four times. Protesters provided aid to Anderson at a medical tent while SPD waited for a Seattle Fire Department ambulance to arrive. However, medics were waiting two blocks away waiting for SPD to tell them it was safe to enter the protest zone.

Despite close proximity to the incident, units were not cleared to enter the protest zone until 2:39 a.m. when a civilian car had already left the protest zone with Anderson to a rendezvous point agreed upon with Seattle Fire, however weren't there when they arrived. The civilian vehicle transported Anderson to Harborview Medical Center where he was pronounced dead shortly after.

Around 11 p.m. on June 29, protesters called 911 to report shots had been fired inside the protest zone. However, dispatchers said they would not be sending police into the area. Callers also described two cars driving erratically, a white Jeep Cherokee and a gold Lincoln town car. Over the next hour, several reports of physical altercations were called into 911, including two more rounds of gunfire at 1:15 a.m. and 2:58 a.m.

The call at 2:58 a.m. indicated the driver of the Lincoln town car fired shots into the white Jeep Cherokee, injuring the 16-year-old driver and his 14-year-old passenger. CHOP medics attempted to provide CPR and apply tourniquets to the victims, but transported them out of the protest zone in personal vehicles after the situation was deemed too urgent.

Medics were directed to a rendezvous point with SPD which was farther away from the shooting than the station they were leaving from. Despite communication between SPD dispatchers providing a description of the vehicle transporting the patient, the ambulance drove away from the car multiple times before protesters were able to catch up with them. By the time they reached the ambulance, the victim, identified as 16-year-old Anthony Mays Jr., had died.

The panel found in both instances that response by city departments and communications between SPD and Seattle Fire delayed lifesaving care to victims. Panelists agreed it was not Seattle Fire's responsibility to enter a potentially unsafe situation, but found SPD was staged too far away from the protest zone to ensure emergency services could carry out their jobs safely.

The chain of communication also delayed care. SPD communicated with dispatchers, who then communicated with the Seattle Fire call center, which communicated with medical units. Panelists found these incidents suggest the need for shared communication methods between Seattle Fire and SPD.

The full report on missteps by the city and the police department is available on the city of Seattle's website. The Office of Inspector General is preparing to release another report on SPD's actions during the later stages of the 2020 protests later this year.

Panel deliberations were co-facilitated by the Quattrone Center for the Fair Administration of Justice, a criminal research and policy hub at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School, and by PointOneNorth Consulting, an organization specializing in peacemaking and conflict resolution.