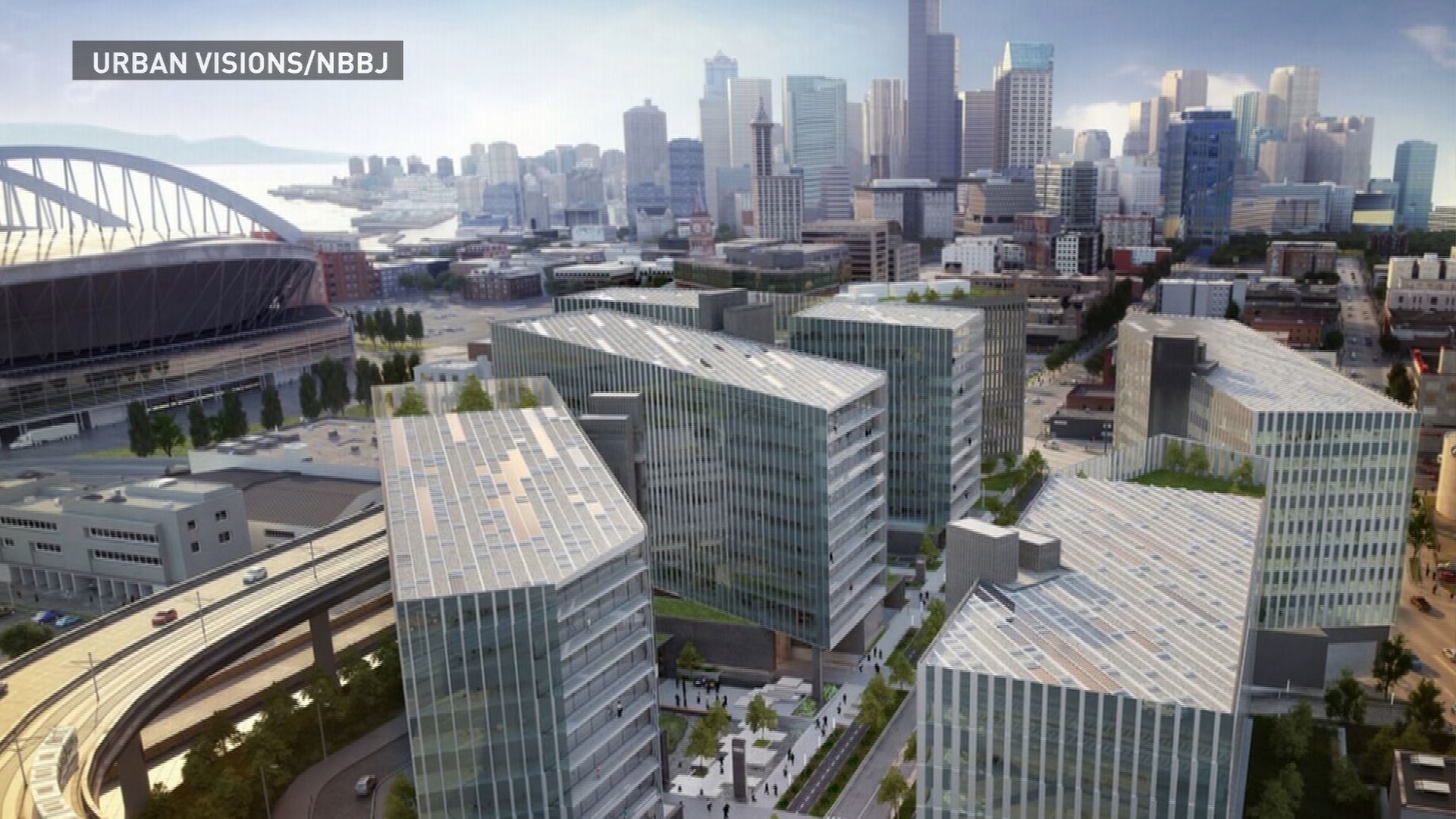

The seven acres south of downtown used to be more marsh-like before Seattle’s earliest planners blasted old hills and carried soil down to this section of town. Now, industrial buildings and car lots like Tesla sit on that soil sandwiched along 6th Ave S and Seattle Blvd S, near the junction of Interstates 90 and 5.

“It’s the first thing you see as you approach the city,” said Greg Smith, CEO of Seattle commercial real estate firm Urban Visions. “It’s on the flight path to Boeing Field and Sea-Tac so you fly right over it.”

Smith knows it’s one reason this is such a coveted spot, and it’s one of the many reasons he wants to build “S” here.

“It’s the largest chunk of land left in the city to create an urban campus,” he said Thursday as he revealed more plans for the big project to KING 5 News.

Seven buildings. One-point-two million square feet of office and street level retail. The price tag could be more than $750-million.

They call it S because of the shape of the buildings.

This somewhat sleepy section bridging Seattle’s International and industrial districts could be home to 5,000 to 6,000 employees. How do you get all of those people to this spot?

“As the car becomes less convenient – I think places that are designed around public transit opportunities are key,” Smith said.

The land will be right on a light rail connection that will send passengers over toward Bellevue and Microsoft’s campus within the next ten years. It’s also a direct link to a bike path across I-90.

Cars aren’t left out of the equation, though. There will be more than 800 parking spaces, Smith said, and there’s attention to how different those cars could be.

“I think one of the big transformations we’re going to see here soon is the introduction of the driverless car and its impact on traffic behavior,” he said. “We’re really in this transformation period of what the impact of the car is going to be on how we think about where we work.”

So in addition to bike rooms and maintenance rooms, designers are dreaming up a different kind of platform: one for self-parking cars.

“You’ll be able to drive in, park your car at the entrance, leave and your car will go park itself,” Smith said. “You have to think about your garages differently now.”

But building a campus in a competitive job and real estate market is causing Urban Visions to dive even further into the design, into what employees are thinking.

“There are things that are intuitive around happiness in the work environment,” said Ryan Mullenix, design partner at NBBJ, a South Lake Union-based design firm working with Urban Visions on the project.

Mullenix said two years ago, NBBJ started working with Dr. John Medina, a developmental molecular biologist at the University of Washington, who’s helping them figure out what makes employees happy.

“We’re finding there’s a lot of correlation: creativity, productivity linked to how space is created; the volume space, daylight, the natural environment certainly factors in,” he said. “99.987 percent of our existence as humans has been outside, and yet we’re cramming people inside buildings, so no wonder people are unhappy in the spaces they’re in.”

He said that doesn’t mean glass boxes. The design will incorporate water, which used to be a big feature of this area, along with natural materials on the first floor and carefully laid out spaces for employees.

“We took all the guts of the building: the cores, the way that people move … elevators, stairs and some mechanical. We pulled them outside of the building so you can see across a floor plate,” he said. “There is a psychology behind moving vertically. In fact, some people say if you’re more than a hundred feet away from a person – you might as well be on a different floor.”

As exhaustive as that might sound to some people, Mullenix said it’s an important factor in recruitment and retention.

“There’s a huge talent war out there,” he said. “Every company is essentially becoming a tech company in certain regards. What does that mean for the market? It means that there’s a lot of talent out there, but I need to draw it where I am, or my competitor’s going to get it.”

Smith hopes to start next year once the plans go through the city’s review process. It could take about three years to build.