Editor's Note: If you are viewing this story in our mobile app, click thislink to see the full story with photos and videos.

Meltdown

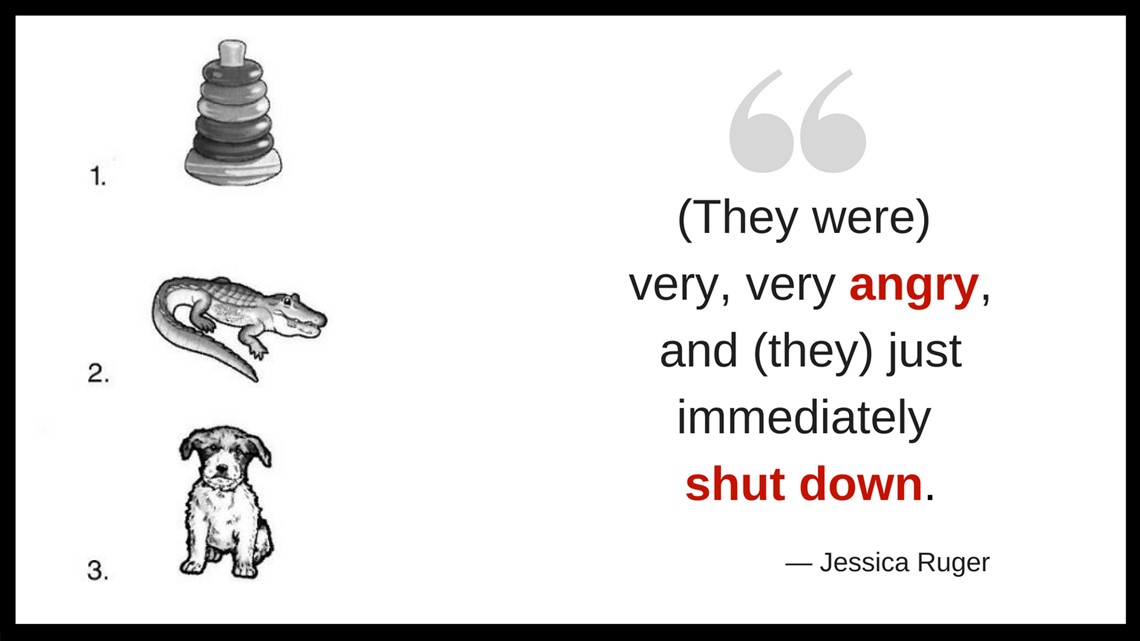

SEATTLE — Ryan Vandell laid face-down on the blue cafeteria table bench and cried as soon as he saw the first three questions on the spelling test — a photo of a toy, a photo of an alligator and a photo of dog.

His twin brother, Jake Vandell, aggressively scratched on his copy of the test with a pencil until he ripped a hole through it.

Then, he crumbled up the paper and threw it across the empty school cafeteria.

That 2014 morning was the start of the twins' second-grade year and their first week at a new school. The boys needed to write the first letter of each word on the 66-question test as part of a reading and writing assessment.

But the twins, who were 7 at the time, didn't even know how to write their own names. Jake could read just five words. Ryan could read two.

"(They were) very, very angry, and (they) just immediately shut down," said Jessica Ruger, the school counselor who oversaw the assessment.

The Sammamish boys, who have dyslexia, were at least two years behind their grade level. Yet, the Lake Washington School District did not teach them using a specialized curriculum for dyslexia intervention. That's an issue because federal law requires public schools to provide the specialized educational services needed for children with disabilities to meet their academic goals.

"They gave them the same instruction that they would give any child who's having difficulty reading or reading slowly— without recognizing that it was dyslexia," said Stacey Vandell, Jake and Ryan's mom. "That is where they failed."

Thousands of Washington families who have children with dyslexia are caught up in the same fight to get appropriate intervention for their kids to succeed in the classroom before they fall too far behind.

Many public schools are not identifying or properly educating students who have the language-based learning disability, according to special education experts and attorneys who work with families. In some cases, school districts will identify students who have the disability, but not until they've fallen years behind in school.

"It's a wait to fail model," said Jennifer Bardsley, an Edmonds-based dyslexia advocate and a former school teacher. "Washington has a very poor reputation within the (national) dyslexia community."

'We Know How To Teach Them To Read'

Dyslexia makes it difficult for students to succeed academically in a typical instructional environment, but it has nothing to do with a lack of intelligence or desire to learn. The disability affects the way people process language. It doesn't just impact reading, but also spelling, writing and pronouncing words, according to the International Dyslexia Association.

Teachers often miss the symptoms of the disability because, for years, the state hasn't required districts to train staff on dyslexia intervention. Experts say the symptoms are often masked by behavioral issues — when a student acts out in class or seems like the class clown.

"I don't think there is a teacher out there that is intentionally saying, 'I don't want this child to learn.' But there are teachers out there that say, 'I don't know what to do.' They are frustrated," said Cindy Dupruy, a local learning disability specialist who has diagnosed hundreds of Washington students with dyslexia."They attribute symptoms (of dyslexia) to motivation. 'Oh, if you would just try harder. You didn't do the work.'"

Dyslexia training is expensive and time-consuming. It's why few Washington schools use a multi-sensory curriculum, even though special education experts say it's the most effective type of intervention for students with dyslexia — and research proves that it works. The curriculum helps students learn to process words by using their eyes, their ears and body movement.

"There's absolutely no excuse that today's schools aren't using effective reading strategies," said Stacy Turner, assistant head of the Hamlin Robinson School, a private school in South Seattle that caters to students with dyslexia. "We know how to teach them to read. It's not implemented effectively in all schools, and it should be."

With appropriate teaching methods, students with dyslexia can learn to read and write successfully. They can eventually flourish in the career paths of their choice. But if it's not caught early and addressed appropriately, special education experts say students with dyslexia can experience a series of issues. That includes poor self-esteem, anxiety and behavioral problems — especially as the academic curriculum becomes more advanced.

"The behaviors get worse and finally reach a point where the school has to address them," said Charlotte Cassady, a Seattle-based special education attorney. "You have to do something about a kid who won't go to school or won't work when she's there or is yelling at a teacher and disrupting the class. But at this stage, the problem—which started as dyslexia—is a lot more expensive to try to turn around, and the turn around is less likely to succeed."

When students with dyslexia don't get the proper support to succeed in school, it's not unusual for them to drop out. Students with specific learning disabilities like dyslexia and dysgraphia dropped out nearly three times as often as their peers in the 2013-2014 school year, according to a 2017 study published by the National Center for Learning Disabilities.

"To think there's a 6-year-old in a classroom who is feeling stupid, who feels slow, who is watching every student get up and turn in their paper one-by-one, and they are stuck there — stuck on the first word. What that does to their sense of self is heartbreaking," said Ruger, the Hamlin Robinson school counselor and the president of the Washington branch of the International Dyslexia Association.

They Refused To Connect The Dots

Long before Stacey Vandell pulled Jake and Ryan out of the Lake Washington School District, the Sammamish mother had to pull her screaming boys out from under the kids' table each morning to make them go to school.

"Just seeing the looks on my kids' faces....I can't tell you how heart-wrenching that was," Vandell said. "We tried to convince them every day (that) today was going to be a different day."

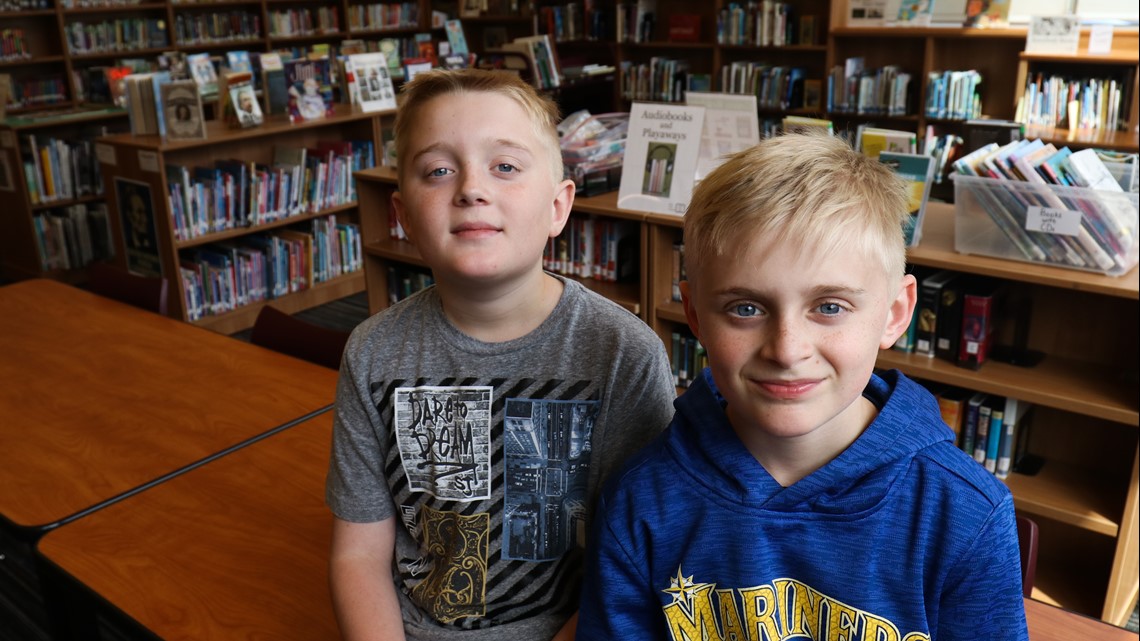

On the outside, the Sammamish twins looked like carefree kids.

But inside, both said they were miserable at Margaret Mead Elementary School. They felt like failures at just 6-years-old.

"It's a spot (in) my life I don't really like looking back at," said Ryan, now 11.

School records spell out the root of the problem for both boys: They couldn't keep up. They had academic deficits, scoring well below average, and they couldn't identify many words.

Vandell said teachers repeatedly told her Jake and Ryan were not focused, and they were misbehaving in class. The district didn't seem to recognize that the twins were acting out because they couldn't comprehend their schoolwork, the mother said.

"(Jake and Ryan) were frustrated. They didn't understand why they didn't understand....They would be held in from recess (for taking too long to finish an assignment). They'd be put in the back of the room. The other kids teased them," Vandell said. "We tried to connect the dots for the school district, and they refused to connect the dots."

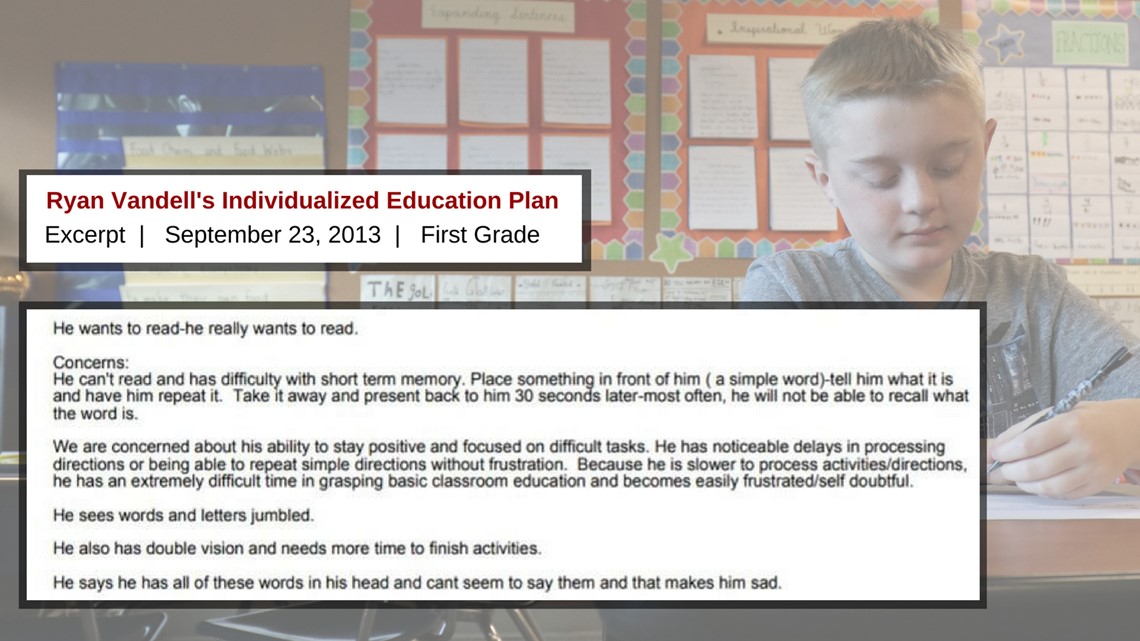

In academic records, school staff acknowledged that the boys could not read or write. But Vandell said school officials never associated the twins' struggles with dyslexia. An independent neuro-psychologist officially diagnosed the boys with dyslexia at the end of Kindergarten, in June 2013, but the district didn't modify their teaching plans, Vandell said.

"They brought up excuses like, 'They're twins. They're boys. They're premature. They're not really interested in learning, and they're immature, too. So they really — they're just not ready. They're not ready to learn,'" she said.

Jake and Ryan both received 20 minutes of reading instruction four times a week, according to their 2013-2014 Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) — the legally binding documents that are intended to help kids with disabilities reach their academic goals. But the twins both struggled to make progress, and teachers never used a multi-sensory curriculum to educate them.

By the end of first grade — their last year at the Lake Washington School District — Jake and Ryan still couldn't say or write their ABCs. Jake couldn't keep simple terms straight — words like breakfast, lunch and dinner. Ryan only could read the words "to" and "the."

Both boys struggled with short-term memory, too. They could not remember simple, three-letter words even 30 seconds after the words were presented to them.

Collin Sullivan, a spokesman for the Lake Washington School District, declined an on-camera interview request to answer questions about the district's dyslexia intervention techniques. He also declined to comment on Jake and Ryan Vandell's experience in the district. He said it was against district policy to talk about specific students.

"Lake Washington School District is continuing to develop supports to ensure that students with reading difficulties, including dyslexia, are identified early and provided with explicit and systematic phonemic awareness, phonics, and fluency instruction that uses multi-sensory strategies," he wrote in a statement. "As always, every student who is eligible for special education receives services that are individualized for their needs."

Sullivan added that the district provided two hours of training on dyslexia research to special education and reading intervention teachers this year.

Next year, he wrote in the statement, elementary teachers in the district will receive the same training. He said 120 teachers will go through five days of training next year to learn a new dyslexia intervention curriculum that the district is adopting, and they'll learn how to screen for dyslexia.

In a separate training, all kindergarten through fifth-grade teachers will attend a one-hour session in August to learn about dyslexia and how to identify struggling readers, he wrote.

'We Have Our Kids Back'

At the beginning of second grade, in September 2014, Vandell moved her twins out of the public school system, and she enrolled them at the Seattle-based Hamlin Robinson School.

The private school, which serves 280 students and costs about $22,000 per year, is designed for kids with learning disabilities, like dyslexia and dysgraphia. Teachers go through a rigorous 133-hour training process to become certified in the multi-sensory curriculum that's taught in every class. It teaches students to use their eyes, ears and body movement to process language.

"It's not one teacher. It's not one classroom. We understand that this is how students learn, and this is how students process language across the board. It's not just your 20-minute reading group," said Ruger, Hamlin Robinson's school counselor and enrollment manager.

Vandell knew the school was a better option. But she didn't expect to see results so quickly from the new curriculum.

On a late 2014 afternoon, Ryan came through the front door —skipping.

After years of watching his older sister's academic successes go up on the fridge, he told his mom he finally had something of his own that was "fridge-worthy." He handed her a light brown sheet of paper— a class assignment, where he spelled out eight words and drew a picture.

"I sat down on the floor in front of it, and I drank a glass of wine, and I cried. I just sat there and balled," Vandell said.

In December 2014, Jake read his first book: Follow Me Mittens. That happened just three months after the twins had a meltdown at the sight of those simple spelling words in the Hamlin Robinson cafeteria.

A month later, in January 2015, Ryan finished his first book, too.

WATCH: Ryan Vandell Reads His First Book

All it took to get there was multi-sensory instruction, tailored to Jake and Ryan's learning needs.

"We went from having shells of children —a shell of our kids —defeated, sad and not confident... to literally months later, confident and happy. We have our kids back," Vandell said.

Jake and Ryan now read chapter books every night, and they write about the stories in a reading journal. Today, they're no longer hiding under the table when it's time to go to school.

"School is my number one priority. I love school. I hope to have more outcomes, but I love it so much," said Jake, who's now in fifth grade. "I am super proud (of myself). I am like proud. I am like prouder than my mom and dad."

Ryan also beams with pride when he talks about his progress.

"I went from like a few months ago reading 68 words a minute (to reading) 108 words a minute," said the fourth-grader. "Now, I feel like I'm flying with flying colors, and I'm doing a great job in math, writing class and seat work."

Law Creates Plan For Schools To Support Dyslexic Kids

While Ryan and Jake had to leave the public school system to make academic progress with their dyslexia, a new law will require Washington schools to get on board with multi-sensory instruction by the 2021-2022 school year.

"The implications of this are not insignificant," said Dupuy, the Washington-based learning disability specialist who has spent more than 15 years evaluating kids for dyslexia.

Senate Bill 6162, which passed the state legislature this year, is a first-of-its-kind plan in the state to ensure that schools are screening, identifying and adequately serving students with dyslexia.

"You are entitled to an IEP if you are diagnosed with a disability. You never have to wait to fail to get an IEP," said Rep. Gerry Pollet (D-Seattle), a who sponsored the House version of the new state law.

The law spells out a multi-step timeline for implementation that spans four years, and it creates a dyslexia advisory council to help accomplish it. Timeline: Implementation of Washington's New Dyslexia Law

Turner, the assistant head at Hamlin Robinson School, said he's pleased that the legislature took the first step to make a difference for dyslexic children but he's worried about how schools will respond once more students are identified. There's a hefty price tag attached to providing the right kind of services for students with dyslexia, at a time when special education in Washington is underfunded by millions of dollars.

"It's going to bring to the forefront the number of students that are at risk for reading failure, and it's also going to push the envelope for the educational system to respond. Identifying the kids that are risk for failure is very different than providing effective intervention, but there needs to be a starting point," he said. "It's a step in the right direction."

Many school districts rely on taxpayer dollars to cover their special education costs, and experts say some schools will struggle to fork out thousands of dollars more for teachers to receive multi-sensory training. Washington school districts reported to the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction that they collectively spent nearly $165 million in local levy funds on special education during the 2015-2016 school year. That money is in addition to what they received from the state.

Dupruy, the learning disability specialist, said she's most concerned that the bill, which won't fully take effect for years, has arrived too late for the students who need help right now.

"I know that we have to start somewhere, but there are a lot of kids who have dyslexia that have (already) been missed in schools. It has closed doors for them, and it will make it difficult for them to be successful in college," she said.

As for Jake and Ryan Vandell, the move to Hamlin Robinson has presented new challenges in their lives.

Now, instead of having a meltdown at the sight of a reading or writing test, the boys mostly face ordinary kid problems, like getting cut in line while waiting to play Four Square at recess.

"Listen, it's a normal school. There's ups and downs, but it's all of those predictable (things)....you get in a fight with your friend, or you didn't have time to finish your snack, and all of those things that school should be," Rugar said. "It's not, 'I'm stupid.'"

Resources And Support

If Your Child Has A Learning Disability

Know your rights. The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction offers guidance for families, which includes a handbook with information about you and your child's rights under state and federal law.

If you have questions about the special education process or difficulties communicating with your school district and need additional help, OSPI has special education parent liaisons available to assist you.

The state also has education ombuds who work with families to answer questions and help resolve concerns. Contact their office online or by phone at 866-297-2597.

About This Series

This story is the fourth part of "Back Of The Class," a multi-part investigation into the state of special education in Washington. The series exposes the reasons why Washington lags behind much of the country in serving one of our most vulnerable populations: students with learning disabilities.

Part 2: Washington kids with disabilities often denied right to learn in general education classrooms

Contact The Reporters

Susannah Frame is the Chief Investigative Reporter at KING 5. Her stories have exposed many wrongs, leading to changes in public policy, congressional investigations, federal indictments and new state laws. Follow her on Twitter @SFrameK5 and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at sframe@king5.com.

Taylor Mirfendereski is a multimedia journalist, who focuses on in-depth reports and investigations for KING 5's digital platforms. Follow her on Twitter @TaylorMirf and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at tmirfendereski@king5.com.