Geologists and geophysicists with the Washington State Geological Survey spent hours checking the ground expected to support the second tsunami evacuation structure in North America.

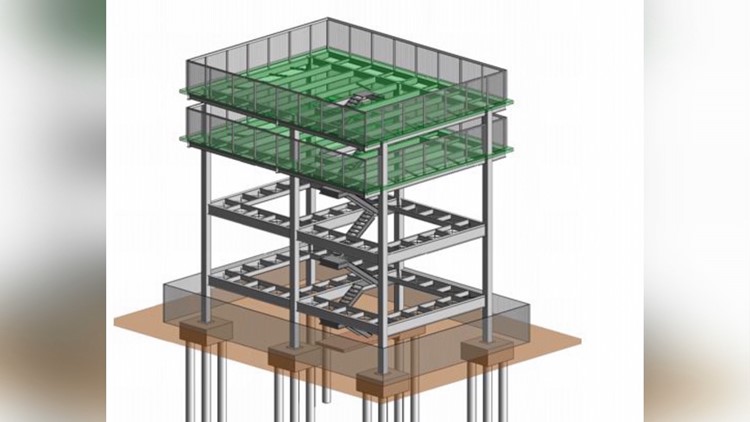

In late June, Region 10 of the Federal Emergency Management Agency awarded $2.2 million to the Shoalwater Bay Indian Tribe to build what’s expected to be a 50 foot, two-deck structure which could hold as many as 1,000 people in a pinch. The federal funds cover 90 percent of the estimated cost.

The tower would give nearly 400 tribal members and several hundred non-members living in the town of Tokeland, south of the reservation boundary, a second place to run in the wake of a strong coastal earthquake expected to result in the kind of tsunami which devastated much of northeastern Japan in 2011. Both the reservation and the town of Tokeland are on a low elevation peninsula.

Currently, people would have to drive or walk to roads leading up to bluffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean but have only 17 minutes to reach higher ground. During the summer, the population swells with tourists and fisherman.

New tsunami inundation maps produced by Washington state show that the tribal village near Highway 105 could face waves of 17 feet. The entire peninsula is expected to be swamped.

The implementation of tsunami evacuation structures in North America is currently the exclusive domain of Washington state communities.

Recently, the Ocosta School District near the town of Westport, on an even longer peninsula, taxed themselves to make their new school into a tsunami evacuation structure.

The dual-purpose building has wide stairways on each corner with doors that open in, which would allow students and staff, along with community members able to reach it to reach the roof. The building is designed with strong concrete columns and breakaway walls to resist the force of waves, which are expected to be loaded with debris from other buildings, floating vehicles, logs and other debris.

The Shoalwater structure would be used solely as an evacuation platform.

The Geological Survey, part of the Washington Department of Natural Resources, is sending seismic waves into the ground to determine what kind of soil and rock the structure would be built on and determine if the soil is vulnerable to liquefaction when sedimentary soils can lose their strength during earthquake shaking. The seismic testing is conducted along with ground-penetrating radar to look for voids such as forgotten septic tanks, pipes and hoping to detect bedrock.

Mike O’Hare, FEMA Region 10 Administrator, said other communities are also looking for ways to get vulnerable populations above tsunami waves.

An earthquake along the Pacific Northwest coast is expected to be as strong as a magnitude 8 to 9 plus. Tsunami waves could keep coming in for 12 hours or more and in places reach 100 feet.

Shoalwater Bay Emergency Management Director Lee Shipman said the tribe hopes to break ground in March 2019 and have the tower open in 2022.