PORTLAND, Ore. — By Thursday morning, the greater Portland area was already seeing the first components of an anticipated ice storm: high winds and bitter cold temperatures. The freezing rain and sleet were expected to begin by evening.

Regardless, the Portland International Airport was already seeing flight delays and cancelations due to winter storm conditions elsewhere in the U.S., and right in the midst of holiday travel.

Delays on the Portland side are more likely to begin once the frozen precipitation arrives, and a statement from Alaska Airlines suggested that they anticipate similar problems in Seattle.

So, what do airport crews do when planes get covered in ice? Most people have probably heard of planes getting de-iced, but perhaps don't know the details of what's involved.

Here's how it works: Typically two batches of liquid are sprayed on a frozen plane. The first is a mix of glycol and water.

Glycol is similar in function to the antifreeze found inside of a car's radiator. The publication Chemical and Engineering News reports that glycol has a freezing point of about 9 degrees and keeps water from freezing until it reaches 58 degrees below zero.

The de-icing crews have to work fast, but also be thorough. The first spray goes on hot, typically between 150 and 180 degrees. It can melt and knock off the ice without freezing onto the plane in turn.

It's important for crews to get all the ice off a plane's wings and tail, because even ice the height of medium sandpaper can significantly increase drag and reduce lift — making it much harder for the plane to fly.

The job of the first de-icing team is to remove all the ice, returning the plane's smooth flying surfaces. This is generally done while passengers are on board, and the crew temporarily closes all outside vents in order to keep the spray from getting inside the cabin.

The Type I fluid, as it's called, is often mixed with an orange dye so it's easy to see.

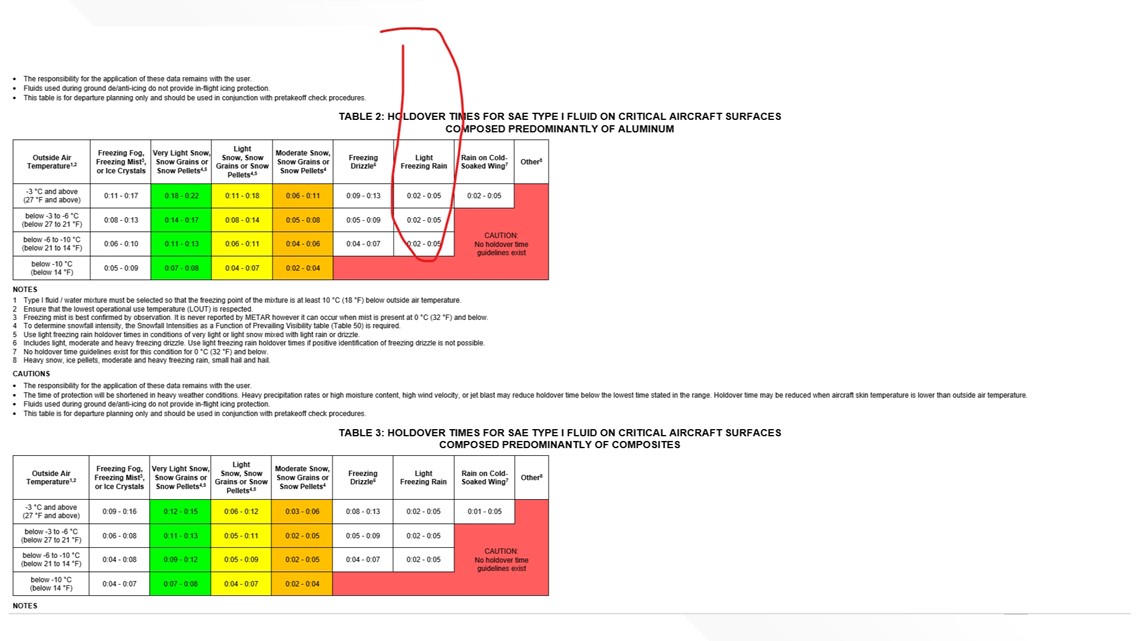

So, how long does Type I de-icer keep the plane from freezing? It can depend. The industry term for this is "holdover time." Basically it describes how long the plane can wait until it needs to be sprayed down again.

In clear weather, the holdover time for Type I is between 5 and 15 minutes, according to Chemical and Engineering News. If the plane can't get airborne that fast, then it needs to be de-iced all over again.

The FAA publishes guidelines for pilots that calculate the temperature, weather conditions and plane composition in order to figure out holdover time. In freezing rain, that isn't much time at all.

RELATED: Portland is getting sleet and freezing rain this week. What's the difference between the two?

If timing is expected to be a problem, crews will often spray a second liquid onto the plane, an anti-ice mix. This is a much thicker glycol mixture, one which stays on the plane's surfaces and helps keep new ice from forming.

Still, even this second mixture doesn't last forever in conditions like freezing rain. Experts say that the holdover time in that case is about 15 minutes, maximum.

Moreover, de-icing isn't a cure-all. Federal guidelines instruct pilots not to take off in moderate to heavy freezing rain, during heavy snowfall or when ice pellets are falling.

In addition to the risk at takeoff, there are also risks associated with flying during these conditions, which can be beyond the ability of "in-flight ice protection systems." That's one reason why severe winter weather can result in extremely lengthy delays and cancelations, not just the wait it takes for crews to do de-icing.