Uncuffed: Former inmate, cop form friendship after rocky start

Officer Jenifer Eshom set out to teach a woman in prison how to live uncuffed. But the cop had her own lessons to learn.

The Other Side

Kandyce Benefield paused and took a deep breath after a corrections officer unlocked the prison gate.

It must have been the 20th time she had walked out secure doors like these. Or was it the 30th time? After spending more than half her life behind bars, the 36-year-old had lost count.

Waiting for her on the other side of razor wire-topped fence was a cop. It was the first time anyone showed up for Benefield outside the gate.

She towed a cart carrying the few items she owned – photos of her now 4-year-old daughter she gave birth to while inside, photos of her prison friends and one self-improvement book. She loaded them into the police officer’s car and hopped in the front seat.

It was one of the few times a police officer didn’t place Benefield in the backseat in a set of handcuffs.

Officer Jenifer Eshom came to teach the ex-convict how to live uncuffed.

WATCH: A KING 5 Original Video

Since 2013, a Seattle nonprofit has paired more than 100 women, like Benefield, with a mentor while they serve out the final year of their sentence at the Washington Center for Corrections and Women (WCCW) in Gig Harbor. School teachers, attorneys, graphic designers, nurses, chefs and college students have all stepped up to help them navigate their first year back into society.

But some of the program’s most surprising volunteers wear a badge in their day jobs. Throughout the years, Eshom and eight other police officers from Seattle, Olympia, Port Orchard and the state's Liquor and Cannabis Board have worked to keep these women out of prison — not put them there. It's a two-year commitment for the officers and other mentors, who—in the first year—meet their mentees at the state’s only maximum-security women’s prison at least once a month and send an e-mail every week. In the second year, they continue to mentor the women after their release.

Against the backdrop of simmering national tension between police officers and the communities they protect, the police officers who join the program as mentors serve another purpose— beyond helping get convicted felons back on their feet. It brings together polar opposites of the criminal justice system to form relationships and, hopefully, see they have more in common than what divides them.

"It’s a really good way to build community, " said Kim Bogucki, co-founder of the If Project, the nonprofit that runs the WCCW mentorship program. ”If you think about these women being mothers, their children probably do not like the police. So all of a sudden, the police are there to help them come home and reintegrate and become more of a support system as opposed to somebody that’s taking their mother or father away.”

In the year and a half since Eshom picked Benefield up at that prison gate in June 2017, their professional relationship has morphed into a sister-like friendship—complete with monthly pedicures and shopping trips.

It didn't start that way.

Different Lives

'I'm Not Going To Tell Her Nothing'

Benefield’s journey began about three years before, when she wrapped her arms around the her baby bump and stared down at her feet during the 20-some minute drive from the Kitsap County jail to the women’s prison.

These rides in the back of police cruisers were so common, they usually didn’t faze her. Being locked up had always felt like home.

But when the Kitsap County Sheriff’s deputy turned a corner past the WCCW entrance sign on this 2014 morning, Benefield looked up and felt unusually sick.

It wasn’t morning sickness.

“Who comes back to prison that soon? Who does that?” Benefield said. “Knowing I’m about to bring a child into this world, and I’m going to have officers right next to me when I’m having a baby wasn’t cool at all.”

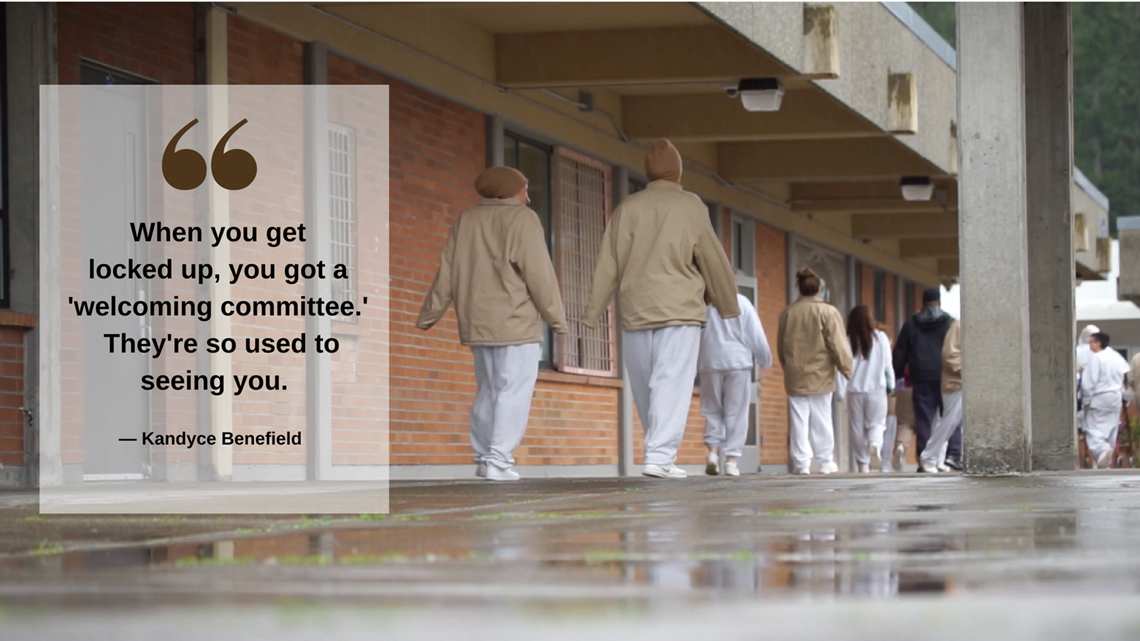

They put her in the same medium-custody unit she lived in until about three years earlier. The same women who greeted 25-year-old Benefield at the start of her first sentence in 2007 were still there — serving out their time.

They were not surprised Benefield, now 32, was back to serve a five-year stint.

“When you get locked up, you got a 'welcoming committee.' They’re so used to seeing you,” she said. "This is the way of life for them, as it was the way of life for me.”

During her first prison sentence, Benefield had no desire to change the lifestyle that brought her there, she said. Prison fights, followed by reprimands were her norm.

But the baby kicking inside her belly now was a wake up call that prison wasn’t supposed to feel like home. If Benefield wanted a shot at raising her daughter on the outside, she knew she had to focus on changing her future.

"I wasn't really that hopeful that that was going to happen," she said. "But I felt like if I gave it a try and if I really gave it an honest try, then I'd know that at least I gave myself a chance at life."

Gradually, Benefield saw a way out of the cycle through the mentorship program. She applied in late 2015 and hoped to be paired up with the court investigator in the group. Or even the pediatrician.

The If Project paired her with a cop.

"I felt like they screwed me over," Benefield said. "I was like, 'This is not who I picked.’"

Benefield hated the police — she had ever since she was a young girl.

"'I'm not going to tell her nothing,'" Benefield told her friends.

She pledged that she would never open her life to a police officer.

“And I'm surely not going to take her into the community with me,” she said. "I'm not going out there telling people that I'm associated with the police. Who does that?”

'Why would I want to invite somebody like that into my life?'

Jenifer Eshom, then 34, glanced down at her wedding ring as she prepared to meet Benefield inside prison for the first time in early 2016.

If the inmate asked about her marriage, Eshom would not talk about her husband, she decided. And she definitely wouldn’t share that he, too, is a cop.

If the inmate asked about her children, Eshom wouldn’t answer. She was even prepared to tell a lie.

As eager as she was to make a real difference in one woman’s life, the 12-year police veteran was hyper-aware of the risk that came with revealing too much about her own.

“I think one of the consequences of the job is a natural distrust of people that you don’t know — especially people who have criminal records,” Eshom said. “Why would I want to invite somebody like that into my life?”

She didn’t yet know what Benefield had done to end up in prison. But Eshom, who worked for the Seattle Police Department, was sure she had nothing in common with a woman who had led a life of crime.

"I walked into law enforcement and this program thinking that if somebody wants to stay out of prison, they will," she said. "'It's so easy. Just stop committing crimes.’”

Eshom joined the Seattle Police Department as a 25-year-old rookie. She went on to patrol the city's downtown and west-side streets for nine years before taking an assignment as an instructor at Washington’s Criminal Justice Training Commission.

She said she signed up for the If Project to fill a void in her career. She’d caught herself becoming increasingly cynical about the job.

“I didn’t feel like I was really making a difference,” Eshom said. “You realize you’re a cog in the machine and you’re just doing triage, but never actually getting a chance at surgery or watching a patient recover.”

In her days on patrol, Eshom looked forward to working complex investigations with many moving parts. More often than not though, she said, she worked mundane “paper calls" — car prowl reports, collisions, burglaries and the like.

“That’s the turning point where cops become angry and jaded and stop caring,” she said. “I could feel myself going in that direction so I actively looked for something to counter that.”

Eshom grew up in the '90s in a three-story suburban home in Renton, raised by middle-class parents who provided everything she needed.

She had her sights set on becoming a police officer at 10-years-old. She said she was inspired by the female DARE officer at her school.

Her parents taught her that cops were important public servants, and that the job was “noble and good.”

In her family police were revered and the people who committed crimes were bad.

“How could I possibly have a connection with somebody who is incarcerated?” Eshom thought. "Of course I’m different. I’m not even on the same level as somebody who is in prison.”

Eshom said she didn't volunteer for this program to make a friend.

“I saw it as kind of like a supervisor to a subordinate,” she said.

She'd already taught hundreds of police recruits at the academy how to be good cops. So she thought it would be an easy task to teach Benefield, too.

"I know how to have a job. I know how to have responsibility. I know how to navigate the world. I know how to pay bills, so I'm going to teach you all that stuff — very non-intimate kind of skills,” she said.

The Human In The Handcuffs

'Breaking Bread'

The crowded visitation room at WCCW reminded Eshom of a middle school cafeteria. In all her years in law enforcement, this was her first time setting foot in a prison.

She wasn’t sure what to talk about during that first meeting alone with Benefield. They'd been e-mailing for weeks, but this felt like an awkward first date.

Eshom looked from left to right as inmates and their visitors trickled in. She wondered: Did all the other prisoners know she was a cop?

She had already planned to keep the cop-speak to a minimum and focus instead on brightening the mood.

"When I first seen Jen... she's just like, 'Bring it in, sister. Give me a hug!'" Benefield recalled.

Eshom tore off a corner of the soggy turkey and swiss sandwich she reluctantly bought from the prison vending machine, and she started talking to Benefield at their assigned table.

“I was trying to dominate the conversation so she wouldn’t ask me any questions,” Eshom said.

“‘Oh you grew up in Massachusetts? What was it like over there?’ ‘What’s prison like? What kind of jobs do they have? What are the classes like?’ I bombarded her with small chat.”

Eshom thought maybe the act of "breaking bread together" would begin a bond. So, she bought Benefield a vending machine meal, too.

Visit after visit, that became their routine: a vending machine lunch and light conversations about topics that allowed the two to avoid talking about themselves.

Benefield was funny and more well spoken than Eshom expected.

"Kandyce is quite a force," Eshom said. "If you're not quite as sharp as her, you're going to miss it because she's really quick-witted.”

The officer saw that Benefield was a planner: A woman who made to-do lists, even behind bars. She showed all the signs of being motivated to raise her daughter and change her life.

"How did this woman ever end up in prison?" Eshom thought to herself. "She seems to have such a straight head on her shoulders."

Benefield didn't trust Eshom enough to really talk.

“I'm like, 'Basically, if this relationship is going to work, you can't be a cop,'” Benefield said.

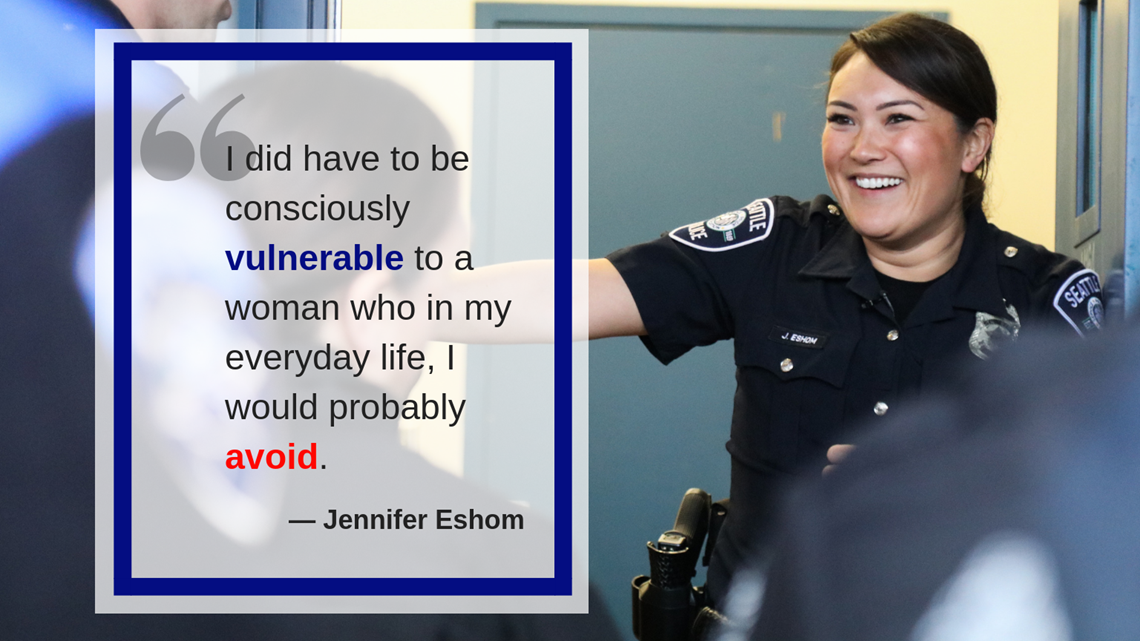

Eshom couldn’t learn Benefield’s story until she could muster up the courage to humanize herself.

"I had to let my guard down a little bit.” she said. “I did have to be consciously vulnerable to a woman who, in my everyday life, I would probably avoid.”

Always Locked Up

Benefield was in prison for a second-degree robbery conviction when she signed up for the If Project.

As excited as she was for the chance at a fresh start, the thought of surviving in the real world terrified her.

“Am I more comfortable inside? Absolutely,” Benefield said.

After all, by her mid-30s, she had spent more of her life living in secure facilities than she'd spent living free. She’d never had a job before. She never had an apartment of her own. And she said she didn’t know a single person that she could trust.

Being "locked up" — in juvenile detention centers, residential treatment facilities, jails and prison — had never felt like a big deal. It was just her "way of life," she said.

And that life was far less traumatizing than the one she had lived on the outside.

“I felt like my destiny was to die like my dad did in prison," she said.

‘I Never Felt Comfortable In My Own Skin'

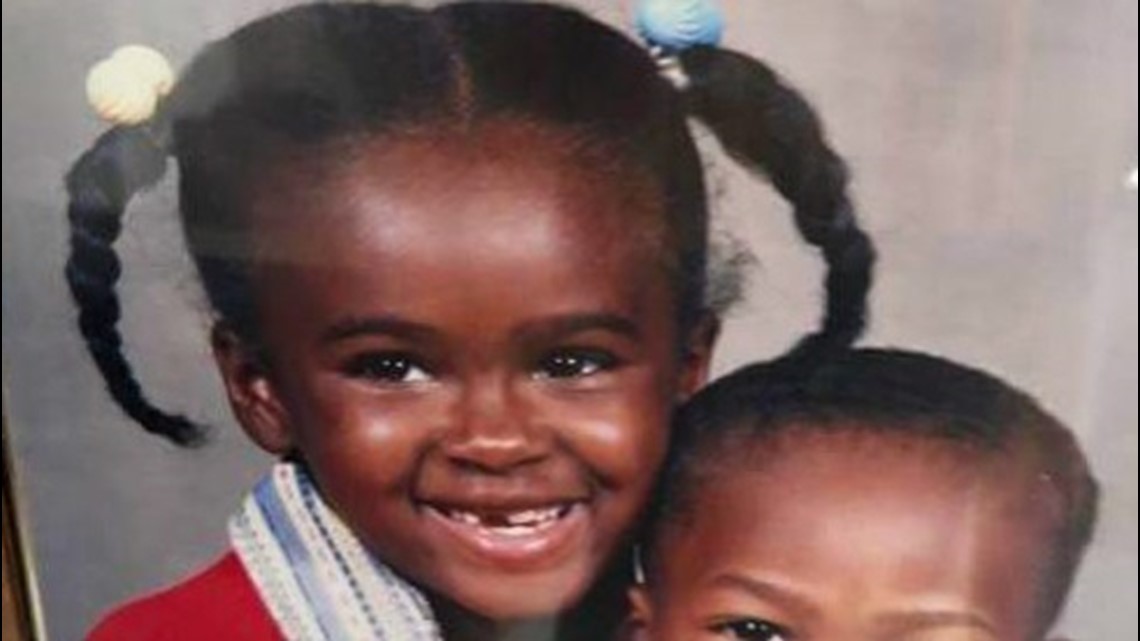

Benefield was 6 the first time she interacted with a police officer. She remembered watching the cop haul her father off to prison. Her dad was the only person who ever made her feel safe, she said.

"I never felt safe with the cops. I just felt like they were never on my side,” she said. "A lot of times when I ran away from home and stuff like that, the cops were the ones who always brought me back home.”

And for Benefield, home was not a happy place.

She lived with her mother in a government housing project in Springfield, Massachusetts. Her mother’s boyfriend molested her for two years, Benefield said, until she turned 8.

"I was very angry. I didn't want people to touch me,” she said. "I always felt like my skin was crawling. I felt I was always trapped in myself. I felt alone."

Benefield said she got into trouble for the first time when she was 8. An officer took her to a juvenile detention center after she assaulted another girl on the playground.

"When I first hit that girl, when I first got in trouble, that was the first time I got taken away from my home,” she said. “It was the first time I felt safe enough to sleep at night — even though I didn’t know where I was, and I was around a whole bunch of strangers.”

Her mother didn’t stay involved in her life, Benefield said, and never believed her boyfriend had hurt her daughter. That catapulted Benefield into a childhood that rotated between foster care homes and running away.

"No one wanted to keep me because I was a violent child. I would act out because I just never felt comfortable in my own skin,” Benefield said.

And when she wasn’t on the streets or in another foster care home, she was in juvenile jails or locked treatment facilities.

Benefield spent her adult years in and out of jail. As she racked up misdemeanor and felony charges, she struggled with untreated mental illness, heroin and methamphetamine addictions, and the absence of healthy relationships in her life.

“You got a lot of people who have parents and stuff in their life and people that are always there. They have that mom, that sister, that brother. I had no one," she said. "Life is hard by yourself and when you're your own best friend all the time, y'know?"

Perhaps the hardest part was figuring out: Where could she go when she had no home?

"I had to figure out how I was going to get to my destination. Sometimes I walked... I would bum money from people to get on the bus until I got to the nearest dope spot or my nearest dealer, (and I'd) go (sell drugs) real quick to put money in my pocket," she said.

"I was just out robbing people, stealing, selling drugs, doing anything that I needed to get by."

Reducing Recidivism

Kim Bogucki, the Seattle police officer who founded the If Project, said Benefield’s experience of lacking a positive adult role model is a textbook reason why many prisoners are arrested again after they’re released.

Eighty-three percent of the state prisoners released in 2005 across 30 states were arrested at least once during the 9 years following their release, according to a 2018 U.S. Department of Justice study on recidivism.

“Women end up getting incarcerated for two top reasons: chemical dependency and unhealthy relationships. So how can we give them a healthy relationship?” Bogucki said.

That was Bogucki’s motivation when she launched the mentorship program six years ago. It's one of several Washington-based initiatives she’s spearheaded to keep people from returning to jails and prisons across the state.

“I never want to take away from what a victim's experience was or try to change their mind about what they went through at all,” Bogucki said. "What we’re trying to do is figure out how to help people successfully reintegrate so that we can reduce the number of victims that are out there.”

Two Mothers

Eshom was curious about why Benefield sat in prison, but she made the decision not to ask about the crime — or even search her name online.

Benefield immediately took notice that the officer didn't focus on all the bad in her life.

"She was just interested in getting to know who I was and what I was about today, and where I was looking forward to going," Benefield said. "She was genuinely trying to help me.”

It wasn't easy for Eshom to look past the unique circumstances of their visits, where guards made the officer give up her personal belongings and watched their every move. But Eshom vividly remembers the first moment she forgot she was sitting in a prison with a woman who had a wildly different upbringing from her own.

It was the 2016 day that Benefield's toddler came to visit. Eshom watched Benefield with her daughter who was about the same age as her own son.

"It humanized her. She looked just like me — just playing with her baby and talking with her baby," Eshom said. "We both had this realization that if we allow ourselves to kind of break down those natural barriers that we'd built up...and meet each other as two women, as two mothers, and look at each other in the lens of those identities, then we were going to be naturally connecting."

They started talking about their children and bonding over board games in the visitation room. Some months, the two would choose a book to read at the same time. They began to discover they had similar, strong-willed personalities. They shared a love for crafts, country music, singing and dancing. They were the same age, and they each harbored similar fears.

"(It was eye opening) to hear that she had weaknesses, too. You know what I mean?" Benefield said. "You hear (about) a cop, and you just think, "OK, nothing hurts them. They don't care. They're above everything because they're above the law because they're the cops.'"

As time passed, the pair started having in-depth discussions about their misconceptions about each other. Benefield began to trust Eshom enough to open up about her past.

"It was really interesting — as I started to form a relationship with her — to see how much of society or how much of her experience I thought I understood, but I really didn't because I have always seen it from the law enforcement side," Eshom said.

"I had really no personal understanding of how difficult it is for somebody to break their own personal cycle of incarceration,” she added.

In July 2016, days after a gunman ambushed and killed five Dallas police officers at a downtown protest, Benefield wrote her mentor an e-mail. It had been six months since Benefield and Eshom first met.

She wrote:

"Even though many ugly things are happening right now, you being part of my life really gives me hope. I wish more people got to see this side of people and even more importantly the police, because maybe they can see that at the end of the day all lives matter. That some bad apples don't spoil the bunch. I really use to feel like I would always be looked at like one of those spoiled apples but people like you helped me realize that I'm much more and people care. So, thank you and your friends (the police) for all you do to help people and keep them safe.

“See you soon friend."

By the time she left prison, almost a year later, Benefield looked to the officer as more than a mentor.

"I felt like I wasn't going back out there alone,” Benefield said. "I wasn't as afraid of failure. I actually had someone that had my back, and she wasn’t police to me anymore. I didn’t care about her profession."

Living Uncuffed

‘Do I Buy This Toilet Paper Or Do I Buy This Toilet Paper’

Benefield completed her five-year prison sentence almost two years early – benefiting from an alternative sentencing program and for serving good time.

But her release from prison wasn’t simple.

“I had focused on, ‘She’s going to be so happy. She’s going to be so relieved. She’s going to feel so much freedom,’” Eshom said.

“I think she was more excited for me to get out than I was,” Benefield said.

Eshom had a list of tasks they’d need to accomplish together right out of the gate. Benefield would have to immediately check in with a Washington Department of Corrections (DOC) officer. She’d need to get a new Washington identification card. And she’d need to buy household items and groceries for her first-ever apartment.

But as soon as they set foot inside a store, Eshom noticed that Benefield’s new freedom overwhelmed her.

“I mean, we’re talking as basic as, ‘Do I buy this toilet paper or do I buy that toilet paper?’ Making that same decision over and over throughout the aisles of Target was totally overwhelming to her,” Eshom said.

“What I hadn't considered was that for the past two or three years, Kandyce didn’t have the luxury or the necessity to really make any decisions for herself,” she added.

In that moment, and in the stressful times that followed, Eshom took control.

“My first day she spent the whole day with me. It was really comforting,” Benefield said. “(It’s) like you’ve been suffocated, like, somebody’s taken your breath away from you and finally you’ll be able to just take a deep breath and breathe.”

In November 2017, about six months after her release, Benefield took a job working the night shift at a Seattle cafe.

At 36, it was the first time she had ever collected a paycheck. She commuted more than two hours each way on a bus to get there.

“The most eye opening thing in this whole experience was how disjointed all of the government systems are in allowing a person to reintegrate into society,” Eshom said.

Eshom said that Benefield’s strict DOC guidelines hindered her from finding a job with a a 9-to-5 schedule. That’s because, at one point, the agency required her to check in with her community corrections officer once a week during daytime business hours. Benefield didn’t have a car.

Because of her work schedule, Benefield’s 4-year-old daughter continued to live apart from her until last fall, when she got married and had some extra support to care for her child and her new stepdaughter.

‘What If I Had Jen When I Was Younger’

In June 2018, a year after Benefield’s release, she and Eshom officially completed the If Project’s mentorship program.

They continue to see each other every month — even though they don’t have to.

The two regularly go to lunch, get their nails done and celebrate significant life events.

Benefield has spent time getting to know Eshom’s husband and youngest son. Eshom has played with Benefield’s daughter. They’ve even held playdates for their two kids.

“I’m never uncomfortable around her — even the fact that she’ll leave her purse or her wallet on the table, little stuff like that,” Benefield said.”It’s not like she doesn’t share her life with me.”

The intimacy the two share is akin to the unspoken affection and impatience of siblings. It is evident in the way Benefield gazes at Eshom when she’s not looking; in the way Eshom holds the hug a little longer than Benefield; in the way they burst into song at the same time. Sometimes, their intense laughter brings tears.

“I sit and I think sometimes, and I wonder, ‘What if I had (Jen) when I was younger?’” said Benefield, who's now 37. “I just feel like it could have stopped a lot for me. It could have really changed a lot of the direction I went in my path.”

‘I Want To End The Mentorship’

Their mentorship hasn’t always been easy.

“We are two very strong-headed women,” Eshom said. “We’ve really butted heads along the way and made each other angry at different points.”

There are times when Benefield doesn’t return Eshom’s calls.

“She did have a rough time in the first few months that she was out,” Eshom said. “And yeah, there were a couple of times where she was MIA and I feared the worst. I thought, ‘She’s relapsed. She’s back on the streets.’"

Other times, Benefield has tried to call the relationship quits.

“She’s even told me that, ‘I want to end the mentorship. I don’t want to be in this program. I don’t want you as a mentor anymore,’” Eshom said.

Those are the days when Eshom shows up at Benefield’s Maple Valley door, and tells her to “get it together.”

“I just keep reminding her that, ‘In the past, you could probably push people away, and they would just walk away from you.’ Very doggedly, I always told her, ‘I’m not doing that’” Eshom said. “‘You can close the door, but I’m still going be on the other side just waiting for you. That’s how much I love you.’”

WATCH: 'I Love That Woman'

Benefield’s transition back into the world outside prison has certainly tested her ability to reshape her path. But she is making strides.

This past December, a year and a half after leaving prison, Benefield completed her probationary period with the Department of Corrections.

“I just feel like I can breathe, and I’m so proud of myself because for once, I wasn’t my own worst enemy.”

She said it’s the first time in her life that’s she’s completed a probationary period without falling back into criminal justice system.

“What I lacked my whole life was purpose,” Benefield said. “I think that’s one of the biggest things that Jen has helped me with is knowing that I matter, and the things that I do matter, and anything I want to do, I can successfully complete it.”

She said she aspires to work with at-risk youth to intervene in their lives before they head down the same path she once took.

Perspective

After years of breaking the law, Benefield is now helping law enforcement.

The Washington Criminal Justice Training Commission periodically hires the ex-convict to speak in front of a class of future Washington correction officers.

“When I talk and I tell my story, it empowers me and it keeps making me do better and wanting to do more to help people get a better understanding so the system works better,” Benefield said to recruits in October 2018. “If we work together, instead of against each other, it makes a big difference.”

It was Eshom who signed up to be a mentor to Benefield. But in the end, the ex-convict also mentored her.

“It’s impossible to ignore the fact that Kandyce has changed my perspective on the experience of incarcerated people and the barriers and struggles that occur when someone is trying to reintegrate themselves into their families, and into society at large,” Eshom said.

“Our mentorship and our relationship has just opened my world,” she added. “She’s helped to re-energize me.”

At the end of 2018, Eshom left the Seattle Police Department and her teaching position at the police academy.

She swore in as a deputy at the King County Sheriff's Office, where she is now responding to 911 calls in south King County.

“(Kandyce) has definitely helped me realize that everybody has a story,” Eshom said. “Everybody has some type of beginning an identity before they got involved in crime.”

Contact The Reporter

Taylor Mirfendereski is a multimedia journalist, who focuses on in-depth storytelling and investigations for KING 5's digital platforms. Follow her on Twitter @TaylorMirf and like her on Facebook to keep up with her work. For story tips, e-mail her at tmirfendereski@king5.com.