SEATTLE — A University of Washington study that mapped methane gas emissions off the Washington coast provides new clues as to how the Cascadia Subduction Zone works.

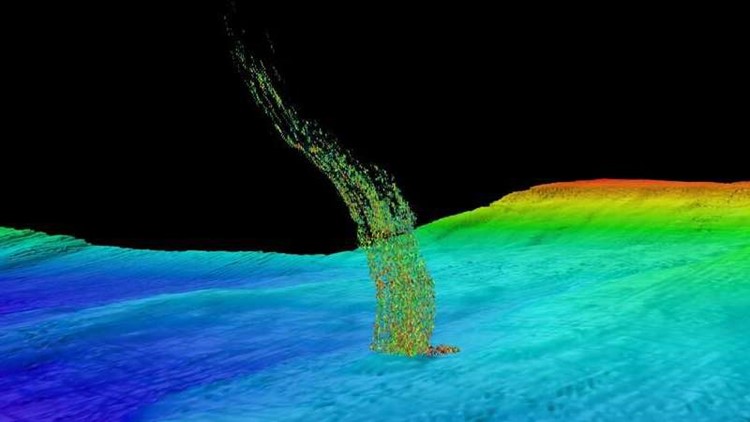

The study, which was published last month in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, documented 1,778 methane bubble plumes grouped in 491 clusters off the Washington coast. The presence of the plumes isn’t new, but UW oceanography professor Paul Johnson, who was the lead author, said he was “stunned” by the sheer number of them.

The bubbles are created when the Juan de Fuca Plate plunges underneath the rigid North American plate. Sediment gets scraped off, which is then heated, deformed, and compressed against the North American plate, squeezing out fluid and methane gas.

They are mostly clustered between the flat continental shelf and the tectonic boundary, where the shelf descends to the ocean floor. After mapping the plume locations, researchers cross-referenced seismic data from oil and gas company surveys from the 1970s and 1980s to interpret why the plumes were located there.

(Red stars show the location of methane bubble plumes. The shallow continental shelf is marked in light gray, and the deeper margin is marked in blue. Map: Paul Johnson / University of Washington)

“The thing that surprised us is that that shelf edge is an atomic boundary – it’s a fault that moves when there’s big earthquakes – and that fault provides a pathway for methane gas and fluid to migrate up and be emitted right there at that shelf edge,” Johnson said.

When an earthquake is triggered, Johnson said the breaking point now appears to be closer to shore than previously thought. That breaking point could be a little over 15 miles from shore in shallower water compared to about 31 miles from shore in the deep ocean trench.

That would mean people on shore could feel the impact of the magnitude 9 earthquake more, but it also means the tsunami would potentially be less damaging.

“If that break instead occurs in shallow water, like 160 meters, you’re moving a lot less water, and that’s a much smaller tsunami,” Johnson said.

Researchers with NOAA and Oregon State University are gearing up to publish another paper that analyzes methane surveys running all the way from Vancouver Island to Northern California, and Johnson says it shows similar trends to the Washington margin.

Some of the plumes discovered were not located perfectly on the subduction zone, which Johnson said probably meant there were other faults that ran perpendicular to the coast.

“One stream (of bubble plumes) that’s running off Grays Harbor…that’s associated with a fault zone,” Johnson said.

However, just because a plume was documented in this study doesn’t mean it will be in the same location when researchers go back. The bubble streams tend to be clustered in groups of five, 10, or 20 streams, and Johnson said the individual streams have a tendency to turn on or off on their own. Researchers don't know why.

But the plumes leave behind evidence: calcium carbonate plates. When methane is emitted, bacteria eats it and forms these plates, some of which formed columns reaching 10-20 meters, according to Johnson.

“They’ve been venting for hundreds of years,” he said.