Washington kids with special needs often denied right to learn in general classes

Washington schools exclude students with disabilities from general education settings more often than schools in nearly every other state in the country, a KING 5 investigation found.

EDITOR'S NOTE: If you are viewing this story in the mobile app, click here for more photos and video.

Excluded From Opportunity

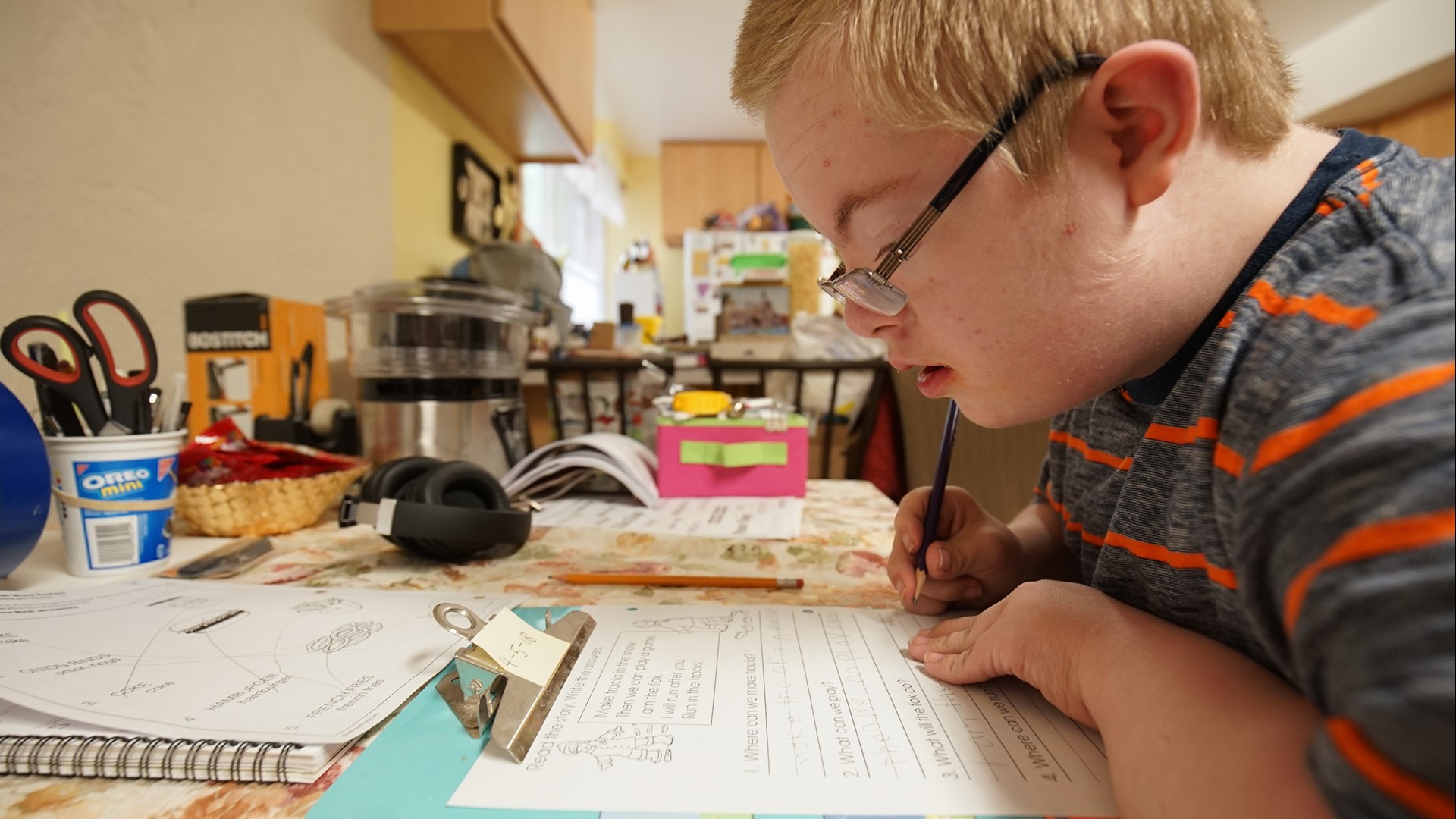

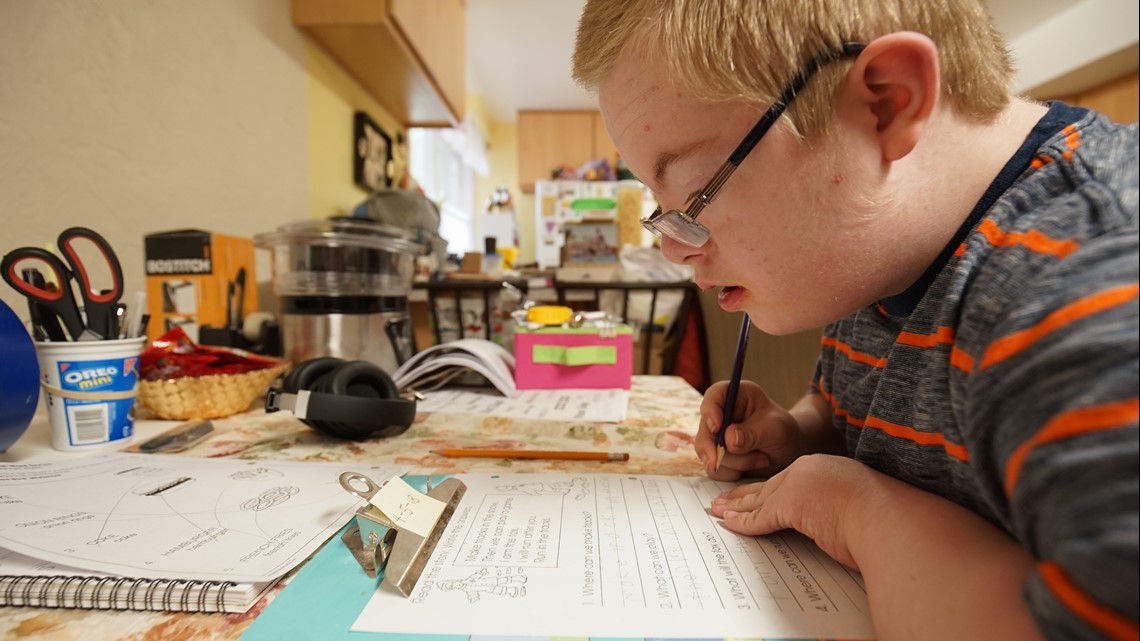

FEDERAL WAY, Wash. — Samuel Clayton got off the school bus and showed the Middle School dance flier to his dad.

"Dance," he said with a big grin, pointing to the word on the flier.

There are lots of words Sam carefully pronounces aloud, but "dance" is one of the few words the 13-year-old can both read and comprehend.

An 8th-grade Taf @ Saghalie student with Down syndrome, Sam thrives on music. He dances at home to nursery rhymes from "The Wiggles." When he plays the ukulele at church, he can't help but move his hips. So when his parents gave him the green light to attend, he could hardly wait to go to his first after-school dance.

When the day of the dance arrived in February, Sam marched into the school gym with his wallet — excited to pay for the $3 ticket himself. Then, he hit the dance floor.

His parents, Sandy and Rob Clayton, stood in the back of the gym and slowly became more and more upset. Their special needs son was surrounded by kids for 45 minutes, but really, he was alone.

"Not one child came and interacted with him. No one came and said, 'Hi Sam.' No one danced with him. No one took a selfie with him," Sandy Clayton said. "He experiences every emotion every other kid feels. He knew he was alone."

It was a wake-up call and a letdown for these doting parents, who concluded: the culture at Sam's middle school is to blame.

"This is an administrative-level problem, and it trickles down to the teachers in the general education population," Rob Clayton, 53, said. "They've set the tone...special needs is not prioritized."

None of the "typical" learners know their son because he spends his entire day in a self-contained classroom with other kids who have disabilities, as set forth in his Individualized Education Plan (IEP) — the legally-binding document that’s intended to help kids with disabilities reach their academic goals.

WATCH: Cell Phone Video Captures Sam Dancing Alone

"He happens to have an extra chromosome,” Sandy Clayton, 52, said. "That’s part of him but it doesn’t define him. But that’s what the other kids see. They see these kids isolated in a class like a Leper colony or something. These are the untouchables.”

The issue is that other kids don’t get to know Sam as a human being— and he doesn't get a chance to learn from them. Sam doesn’t even sit with the typical learners at lunch, his parents said, even though it's his legal right to be around his non-disabled peers as much as possible.

“You get the sense that your kids are just taking up real estate in the school,” Sandy Clayton said. "It's just shoving them aside. It's like they don't exist."

Like Sam, thousands of other special education students in Washington state are shut out of regular classrooms. A KING 5 investigation found that Washington schools exclude students with disabilities from general education settings more often than schools in nearly every other state in the country.

That’s not supposed to happen under state and federal law. Public schools in the United States are required to provide specialized educational services to all children with a disability recognized under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

That law guarantees that the more than 150,000 special education students in Washington have a right to go to school in the “least restrictive environment.” It means they should get the opportunity — to the maximum extent appropriate — to learn in a general education setting around children who are not disabled, even if they can’t keep up academically or if schools have to modify the way the children learn with extra support.

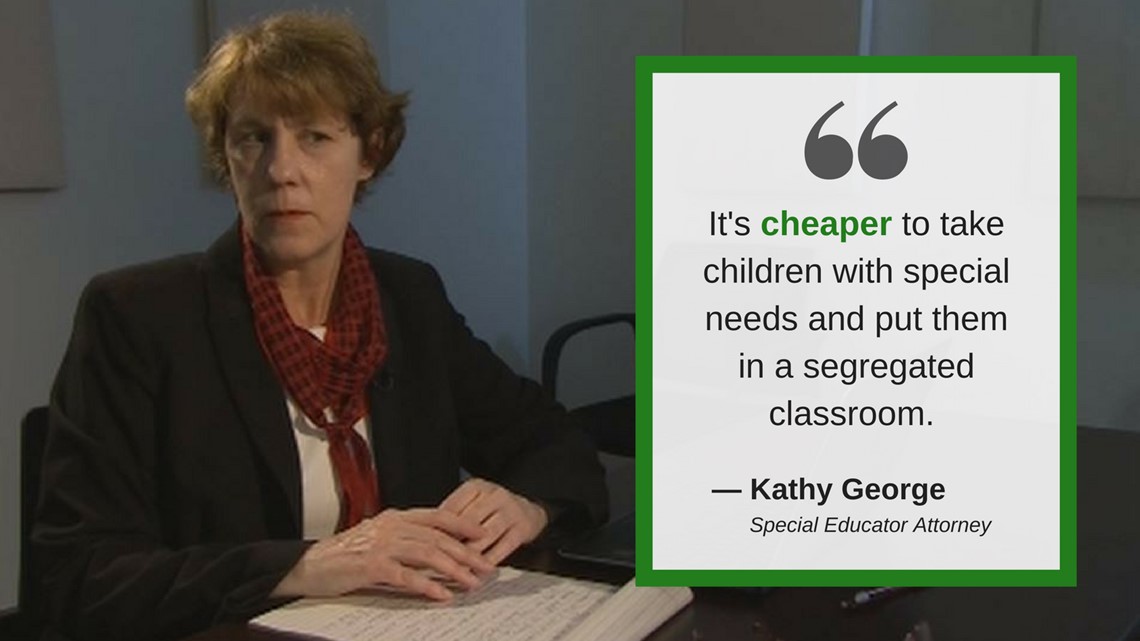

"I see all too often that kids are removed from the regular classroom unnecessarily when they are capable of learning with the right support,” said Kathy George, a Seattle-based attorney and a special education expert.

.

School officials can only remove students from the general education environment if their disabilities are so severe that they aren’t able to achieve goals set in their IEPs, even when students are assigned a personal-tending aide and other individualized services. It’s why IEP teams assign a percentage for the amount of time each special education student should spend with his or her non-disabled peers.

It's common and appropriate, George added, for educators to pull students with cognitive impairments out of the regular classroom for individual instruction in math or reading.

"But what about (physical education)? And what about music? Or art? You know, these are the types of classes that really shouldn’t be excluding kids based on cognitive disabilities,” she said.

Just over half of Washington's 6 to 21-year-olds with disabilities spend 80 percent or more of their day in general education classes. Only seven states have a lower percentage of special education students in regular classes, according to an analysis of the U.S. Department of Education's most recent IDEA report to Congress published in 2017.

Five percent of Washington's students with intellectual disabilities spend the majority of their day in regular classrooms. Only two states in the country — Nevada and Illinois — have worse inclusion rates than Washington in that category, according to the same report.

“We’re clearly a state that has a lot of work to do,” said Chris Reykdal, superintendent of the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction.

Inclusion Improves Outcomes

When schools adequately include disabled students in settings with their non-disabled peers, it can be life-changing, according to experts who cite nearly 30-years of inclusion research.

"What the research tells us is that children with disabilities do better when they are in inclusive classrooms,” said Ilene Schwartz, a University of Washington professor and a national expert on inclusion in schools. “There’s no negative effect on typically-developing children."

Inclusion helps students with disabilities perform better academically, she said, but it also gives these students a sense of belonging that encourages them to finish school.

That's noteworthy because only 58 percent of Washington special education students got diplomas in 2016. A 50-state analysis of graduation rates reported to the U.S. Department of Education shows that just 12 states, including Alaska, Georgia and South Carolina, graduated fewer kids with learning disabilities than Washington that year.

"There’s a high moral and social cost when someone is not able to leave the educational system employable, to be able to live independently and be able to sustain their own needs,” said Stacy Gillett, executive director of the Arc of King County and the former Washington Education Ombuds under Gov. Jay Inslee.

Washington has one of the worst track records for being able to keep students with disabilities in school. According to the Department of Education's most recent report to Congress, 34 percent of Washington's special ed kids are dropping out. Only two states in the country, Utah and South Carolina, reported a higher dropout rate over the same time frame.

"Including them from the beginning — from early on — is the only way they have a chance to keep up with their peers and to learn the same things that we expect all kids to learn in Washington school,” George, the special education attorney, said.

Most Washington students with IEPs do not have severe cognitive disabilities. They’re capable of reaching the same academic level as their peers with specialized support, according to experts in this field. Some of those students on IEPs have dyslexia or sensory processing issues. Others struggle with emotional disorders or attention deficit disorders.

But students with intellectual disabilities, like Sam Clayton, can benefit from spending time in a regular class, too. Experts say the social skills the students can take away from modeling their typical peers are invaluable.

Sandy Clayton worries that Sam has grown fearful of kids his own age because he hasn't had ample opportunities to interact with them for the last three years.

"There's so much that he could gain from being with typically-developing kids his own age -- conversation skills, developing interests and just learning to be around other people," she said.

The mother is also concerned that her son's social skills have taken a step backward from his elementary school days, when he had more informal and formal ways to interact with his non-disabled classmates.

His IEP records show that he was in a general education setting for four percent of the week in 5th grade, compared to no time in a regular classroom this school year in 8th grade,

In Rob and Sandy Clayton's eyes, that mere four percent wasn't sufficient either but something was better than nothing. At least those elementary school classmates knew Sam by name.

"We could go anywhere in the community and the kids would come up and say 'Hi Sam!'' Sandy Clayton said. "The kids wanted to help him and mentor him, and they got their own sense of pride from that. They could see that Sam is much more like them than unlike them."

Funding A Roadblock For Educators

Washington's poor inclusion rates stem from an underfunded state special education system that leaves students with disabilities in limbo and school districts scrambling to comply with the law, educators and special education experts say.

But the state is not forking out enough money to its schools to fund the actual cost of providing services to kids who have special needs, a KING 5 investigation found. That shortfall forced the state's school districts to come up with nearly $165 million in taxpayer dollars on their own to help cover their special education expenses in the 2015-2016 school year, according to OSPI.

Overall, classroom overcrowding in general education is an obstacle to integrating kids with disabilities. Plus, schools can’t always afford to pay for paraeducators — the one-on-one aides who help the neediest students succeed in the general education setting. Under Washington's funding model, the state pays for less than one teaching assistant per school.

"It’s cheaper to take children with special needs and put them in a segregated classroom with one teacher and maybe a couple of (aides) than distributing them across mainstream," George said.

But even so, school districts aren't legally allowed to remove a child from the regular class simply because there is no aide available to help the regular classroom teacher.

Teachers like Martha Patterson see the funding impact firsthand. She said some of her most capable special needs students were denied access to the regular classroom because of resource constraints.

“I had eight to 10 kids in six different grade levels,” said Patterson, a former Bremerton teacher who currently teaches in the Central Kitsap School District. "Myself and two-to-three paras were supposed to get them into general education classes with support as much as possible, and it just was not possible because we didn’t have the manpower.”

Shannon McCann, president of the Federal Way Education Association and a middle school special education teacher, said she experienced the same problem in the Federal Way School District, where Sam goes to school, because the classes were too full with typical learners.

"If we are serious about inclusion then we need to be serious about staffing levels of both paraeducators and teachers,” said McCann, who’s on leave from her teaching assignment at Totem Middle School due to her current role as union president. "Scheduling has a huge impact on how kids can access the kind of education they deserve.”

Carrie Basas, director of the Governor’s Office of the Education Ombuds, said the lack of resources is about more than money.

For students with special needs to do well in a regular classroom, she said, general ed teachers must have access to deeper training on individual disabilities. Plus, they must have proper in-classroom support and the support of school leadership.

"Resources can be about principal training, too," Basas said. "Principals can have a role in really guiding what inclusive practices look like, and also how to use other resources around the school to support the student.”

But even across districts, leadership can change the course of a special needs student’s future.

"It’s varying school by school and region by region. It’s maddening. Each school has its own personality,” said Lara Hruska, a Seattle-based education attorney and special education expert.

It's up to the members of a student's IEP team to decide what educational placement is the best fit because there's not a common set of standards for all students. But Hruska said members of those teams sometimes use "1970s garbage" -- her way of describing an old-fashioned approach to including students with their non-disabled peers.

"Philosophically, a school may look at an evaluation and say, 'Based on this student’s cognitive testing, she can’t possibly be included. Maybe they’ve never seen it done well," she said.

Sam Clayton's dad, Robert, agrees that his son's circumstances could improve with a cultural shift.

"It's a way of thinking outside the box or outside the system that will move things forward, and it doesn't cost money to do that," he said.

Reykdal, the state's top educational official, doesn't deny that some of the state's school districts have philosophies that don't support inclusion. He said Washington schools are going to have to do better at modifying their general education curriculum for three to four different types of learners.

"It's not unimaginable to me that all our historic practice of exclusion and isolating and creating resource rooms...has been a persistent thing that's hung with us," he said. "The entire science of learning has changed about that, and we are a state that's going to have to work a lot harder than others."

It's not just a legal argument that schools have a responsibility to meet students at a level that's appropriate for their needs. William Wadlington, superintendent of the Columbia School District in Stevens County, says it's a moral issue, too.

"It’s more costly to put them in a regular classroom, but ethically and morally you can’t just throw them into a resource room," he said. "It doesn’t make sense to take a kid who is a little behind in reading and make them behind in everything else."

Inclusion Isn't 'Dumping Kids' In General Ed

Hruska, who has represented more than 100 local families in special education cases, said she sometimes must fight for students to be placed in more restrictive settings, like in cases where school districts simply checked off a box.

"I have clients who are often irresponsibly dumped in the general education setting, and that’s not inclusion,” she said. "Inclusion is difficult, and it’s complicated, and it requires significant skill and supports."

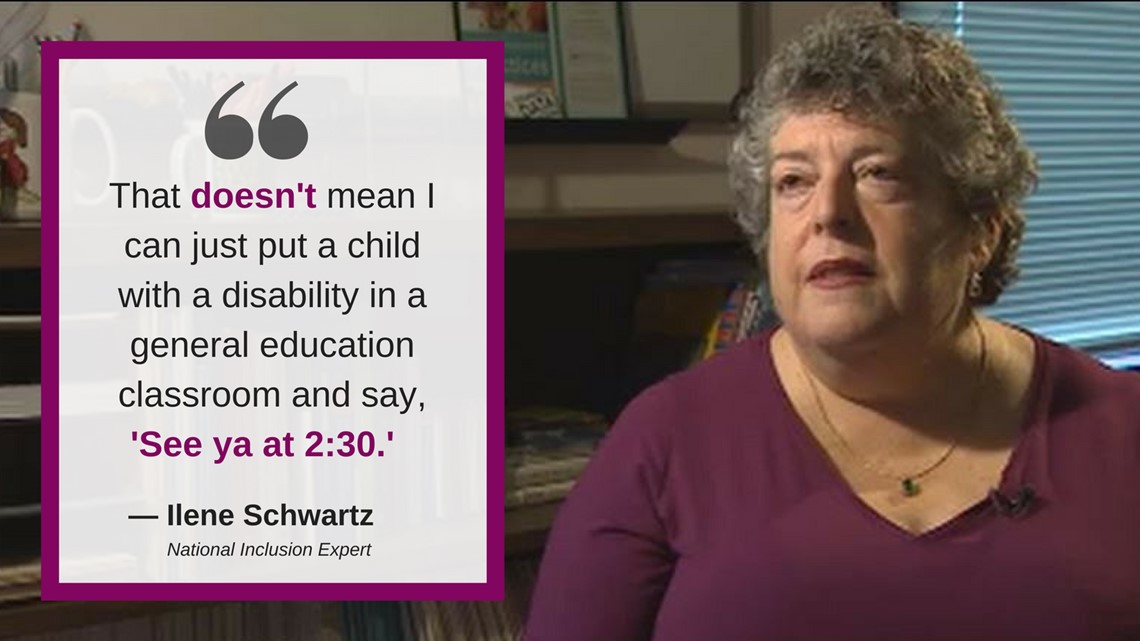

Schwartz, the UW-based national inclusion expert, said that the reality is that schools aren’t supposed to put a child with a disability in a classroom by his or herself.

"They come with support. They come with consultation and special ed teachers. Often, they come with para-professional help. They come with consultation from the occupational therapist and physical therapist and sometimes a psychologist so there’s a team,” she said.

"That doesn’t mean I can just put a child with a disability in a general education classroom and say, ‘See ya at 2:30,’" she added,

A Case For Inclusion

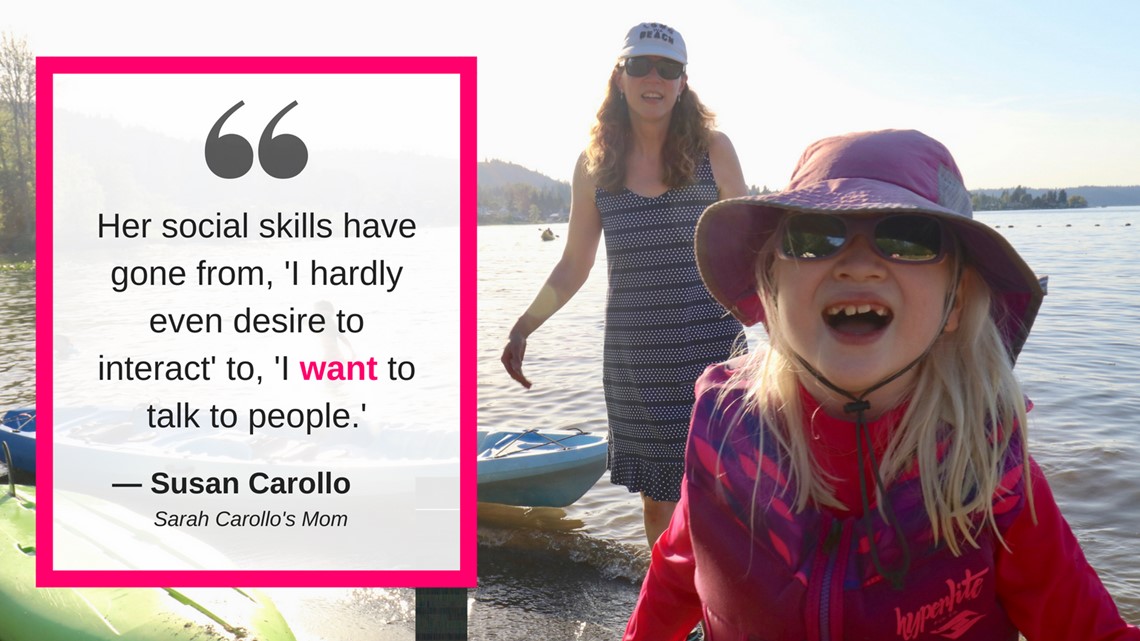

Susan Carollo fought for meaningful inclusion in the Lake Washington School District for years.

The 46-year-old Sammamish mother of four was less than satisfied when McAuliffe Elementary School staff proposed to keep her now 7-year-old daughter, Sarah, in a self-contained kindergarten program for more than 80 percent of the school week.

"I was appalled. I could not believe it," Carollo said.

Sarah, who has albinism and autism, only spent time with her non-disabled classmates for 20-to-30-minute visits in the mornings and afternoons, in addition to recess and lunch.

"It made her a visitor. She did not feel like she belonged to the class," Susan Carollo said. "All the kids know which students are visiting from a self-contained program. They know those kids are disabled kids, even if they are sweet and kind to them. There is still a sense that they belong somewhere else."

Sarah struggles with social interactions and has trouble communicating effectively because of her autism. She has limited vision due to her albinism.

Still, Susan Carollo was convinced that her daughter has the capacity to flourish with the support of a personal aide in the regular classroom.

After all, Sarah is a precocious girl who learned how to read before she started Kindergarten. She has a passion for flags, science and the human body's digestive system. Last year, she asked her mom if she could dress up as an intestine for Halloween. She settled for a skeleton costume.

"It was just so obvious to me that she needed to learn social skills and practice them with typically-developing kids," her mother said. "Because if you just have kids with autism learning from each other, one might say 'hi' and no one will answer because they might not be ready... I just can't imagine how hard that would be to learn anything."

Carollo pleaded with her daughter's IEP team to increase Sarah's time in the general education setting to at least 50 percent of the school week.

The district denied the mother's requests because officials said they wanted to observe Sarah in her new Kindergarten setting before increasing her time with typical learners. They added that it was more restrictive to place Sarah in a regular classroom with a personal aide than to keep her in the self-contained classroom.

It's a myth among school districts that special education attorneys have historically challenged.

"They will say things like ‘It’s a Velcro.’ 'It’s a shadow.’ Or, 'a student will have learned helplessness if there’s an adult hovering over them,’" said Hruska, the special education attorney who Susan Carollo hired to help her challenge the district's placement decision,

Carollo eventually moved her daughter out of the district full time. She enrolled her in a private school in Issaquah where, as a first-grade student, Sarah is included with her non-disabled peers for the full school day. Carollo's private insurance covers an aide to go to school with Sarah every day to help her stay on task.

"She's doing the same curriculum. Some things might be shortened -- like 8 spelling words instead of 12 -- and the questions involving long verbal explanations for math are skipped. But she does the same worksheets as everyone else," Carollo said.

The mother said she's pleased and surprised by Sarah's academic progress, vocabulary skills and social confidence in the last year.

"Her social skills have gone from, 'I hardly even desire to interact,' to 'I want to talk to people.' It's a total turn around, really," Carollo said, adding that Sarah's finally getting invitations to birthday parties and making friends. "She's seen as a real, valid class member. Not just a visitor, but an actual potential friend."

One of the biggest benefits of the move, Carollo said, is that the expectations for her daughter dramatically increased when she mixed in with typical learners for the full school day. Sarah was never exposed to chapter books in the self-contained classroom, her mother said, but today she loves to read them.

"I'm just glad we had the opportunity to go a place where the teacher is amazing and gives her confidence. That's an important thing we lost at McAuliffe (Elementary)," Carollo said. "They saw her as a collection of deficits, and what she can't do as opposed to being in the (private school) class where they have high expectations."

Schwartz, the UW professor and national inclusion expert, said the reality is that kids will succeed more often when you challenge them to work past their comfort level.

"Kids are unique. They are all individuals. All humans like to learn, and when we put them in those situations they’ll show us that they have strengths that we may not have known they had," she said.

In June 2017, Carollo filed a complaint with OSPI against the Lake Washington School District. She claimed the district failed to follow the law when determining the least restrictive placement for her daughter. The district denied that allegation, according to the complaint.

Two months later, OSPI ruled that the Lake Washington School District erred by failing to properly consider whether Sarah could participate in a general education setting with a one-on-one aide. And the state agency shot down the district's claim that it was a more restrictive placement for Sarah.

Because of the decision, McAuliffe Elementary School amended Sarah's IEP, indicating that she could spend more than 80 percent of the day in the general ed classroom.

It was a big win for the Carollo family. But since Sarah is making progress in the private school, her mother decided to keep her there.

"I look at this as sort of a year by year decision, but I definitely want her with typical peers wherever we can find that," Carollo said.

A spokeswoman for the Lake Washington School declined to discuss Sarah's case or answer questions about whether or not there have been district-wide changes as a result of the OSPI decision.

'It Can Be Overwhelming'

While the Carollos had the means to consult with an attorney and file a formal complaint, some parents -- like Rob and Sandy Clayton -- are stretched too thin to challenge their child's school district.

"If I'm perfectly honest, for all the joy of having a child with special needs, it can be overwhelming -- the administrative part of it, the paperwork, the laws." Sandy Clayton said. "I want to spend time with my kid. I don't want to spend all of my day focused on his disability and how to make people be fair to him."

At home, the Claytons do their best to make up for their son's segregated school life by taking him out into the community. They've raised a son who's a swimmer, a drummer, a tennis player, a church member, a ukulele player and more.

But they still worry that Sam's only seen as the "disabled kid" in school.

WATCH: 'Maybe I Should Have Pushed Harder'

Sam's middle school educational records show he isn't close to meeting the majority of his goals in reading, math or social skills. Instead of re-thinking the structure, Federal Way administrators still keep Sam separate.

"Legalities aside, it's a moral shame," Sandy Clayton said.

A Federal Way School District spokeswoman declined to talk about Sam's case, citing the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act.

"What we can share is we have partnered with this parent, like all parents, to develop the content of what is in the IEP based on what we know about the child's needs," Kassie Swenson, the district communications director, wrote in a statement. "If there are any concerns or questions to support our students' education needs, we welcome our parents and families input and encourage them to contact the school or district."

Swenson also denied multiple requests for an in-person interview with the district superintendent to discuss inclusion practices in the school district.

She said, in another written statement, that the school district is following state and federal law, and it has procedures in place to support students in the least restrictive environment.

"Our goal is to provide best practices for inclusion so scholars receiving services have access to high-quality core curriculum," she wrote. "We recognize some of our schools are further along than others and we are taking action to assess and make any necessary improvements to our program."

Rob and Sandy Clayton hope the high school Sam will attend next year will be more inclusive.

Though, they acknowledge it's too late in the game for Sam to be totally mainstreamed with typical learners because he never really learned how to function in a setting that isn't self-contained.

"I don't think it's necessarily realistic... but that doesn't mean there can't be a compromise," Sandy Clayton said. "I think when you challenge people, sometimes they rise to the occasion."

Clayton hopes the future will also challenge her son's non-disabled classmates to get out of their comfort zones and say "hello" because she wants them to have the great benefit of meeting and learning from Sam, too.

"I feel really sorry for the other kids because there's something very special about the kids in Sam's class," Sandy Clayton said. "It goes beyond academics or ability. These are kids who work really hard, who love hard, who don't go out of their way to tease or bully. They're really genuine kids."

Resources and Support

If Your Child Has A Learning Disability

Know your rights. The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction offers guidance for families, which includes a handbook with information about you and your child's rights under state and federal law.

If you have questions about the special education process or difficulties communicating with your school district and need additional help, OSPI has special education parent liaisons available to assist you.

The state also has education ombuds who work with families to answer questions and help resolve concerns. Contact their office online or by phone at 866-297-2597.

About This Series

This story is the second part of "Back Of The Class," a multi-part investigation into the state of special education in Washington. The series exposes the reasons why Washington lags behind much of the country in serving one of our most vulnerable populations: students with learning disabilities.

Contact The Reporters

Susannah Frame is the Chief Investigative Reporter at KING 5. Her stories have exposed many wrongs, leading to changes in public policy, congressional investigations, federal indictments and new state laws. Follow her on Twitter @SFrameK5 and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at sframe@king5.com.

Taylor Mirfendereski is a multimedia journalist, who focuses on in-depth reports and investigations for KING 5's digital platforms. Follow her on Twitter @TaylorMirf and like her on Facebook to keep up with her reporting. For story tips or questions, e-mail her at tmirfendereski@king5.com.