Jennifer Weiner’s entertaining stories of women’s lives, from In Her Shoes to Good in Bed, have earned her a devoted fan base among grownups.

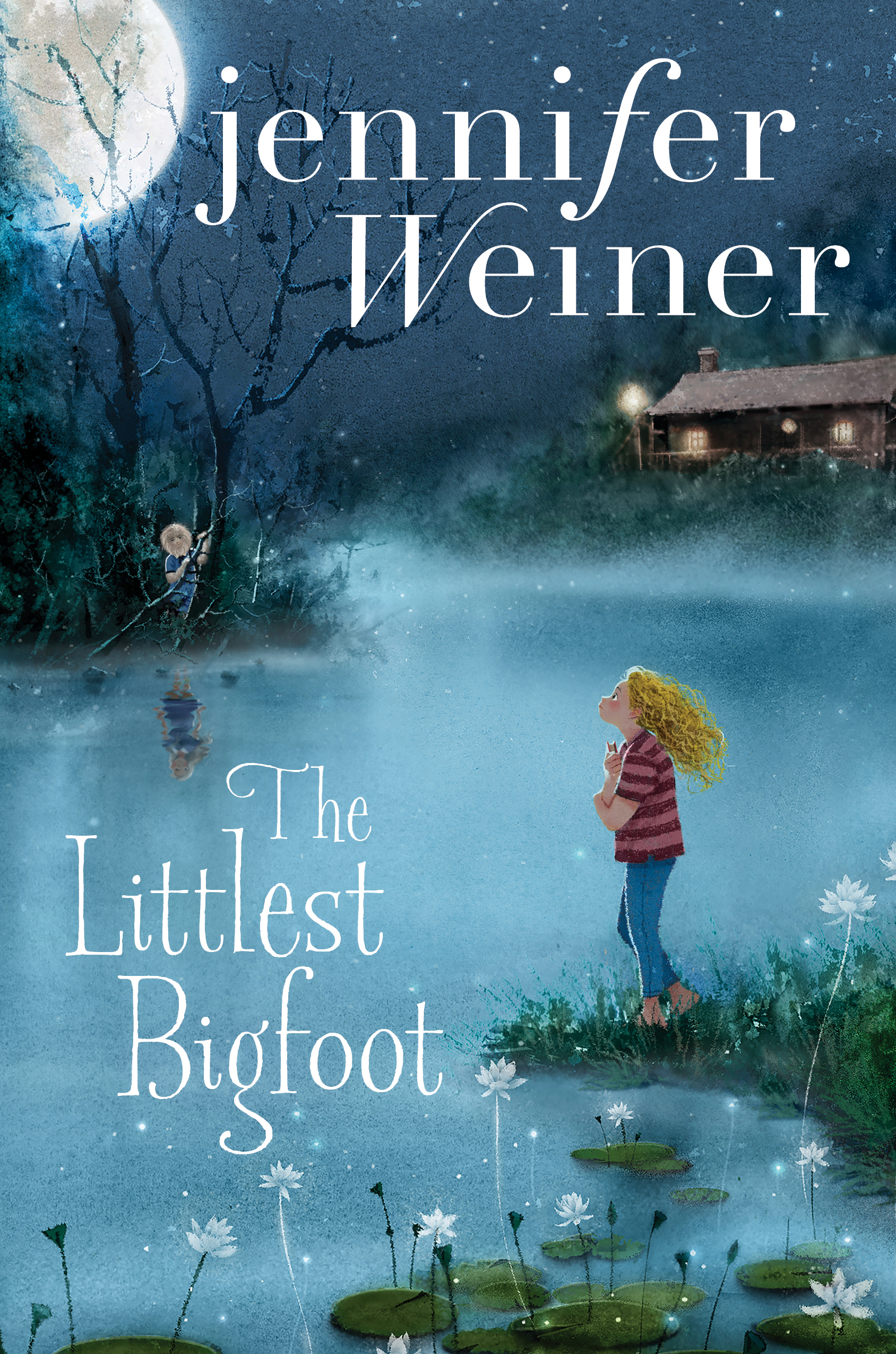

Now the novelist is making her first foray into writing for kids, with the fantasy-tinged middle-grade debut The Littlest Bigfoot, which Aladdin (an imprint of Simon & Schuster) will publish on Sept. 13.

It’s the first in a planned trilogy, and USA TODAY has a first look at the jacket here, and an exclusive excerpt below.

The Littlest Bigfoot is the story of 12-year-old Alice Mayfair, a misfit who is ignored by her own family and shipped off to boarding school. She’d love a friend, and one day she rescues mysterious Millie Maximus from drowning in a lake.

Millie, it turns out, is a Bigfoot, part of a clan that lives deep in the woods. Alice swears to protect Millie and her tribe, and the two girls try to find a place where they both fit in.

“The Littlest Bigfoot started as a story I told my daughters, and it's the kind of book I wished for when I was a kid,” Weiner says. Alice and Millie “are both outcasts in their own worlds — too big, too little; too strong, too weak — but are perfect in each other's eyes. As they work to keep Millie's hidden Bigfoot world a secret, they learn that they don't have to fit anyone else's idea of strength or beauty to find happiness and love...and that they never have to wait for a prince, or a boy, to save the day.”

Weiner has had 12 USA TODAY best sellers, including last year’s Who Do You Love, which reached No. 5. Her next book for adults, It’s All Material, a collection of autobiographical essays, will be published by Atria on Oct. 11.

Aladdin plans to publish books 2 and 3 in the Bigfoot trilogy in fall 2017 and fall 2018.

Read an excerpt from the first chapter of The Littlest Bigfoot:

Chapter One

On a clear and sunny morning in September, a twelve-year-old girl named Alice Mayfair stood on the corner of Eighty-Ninth Street and Fifth Avenue in New York City and tried to disappear.

Vanishing was Alice’s special talent. Some girls were good at math, and some were good at sports or drama or singing. Alice was good at making herself go away.

She was tall, so she slumped, curving her spine into the shape of a C, tucking her chin into her chest. She was wide, so she pulled her shoulders close together and hunched forward, with her gaze focused on the ground. Her hands, big and thick as ham steaks with fingers, were always jammed in her pockets. Her big feet were pressed so closely together that a casual observer might think she had a single large foot instead of two regular ones.

Her hair was the one thing she couldn’t subdue. Reddish-blond, thick, and unruly, Alice’s hair refused to behave, no matter how tightly she braided it or how many elastic bands she used to keep it in place. Living with The Mane, as she called it, was like having a three-year-old on top of her head, a little kid who refused to listen or be good no matter what bribes she offered or what punishments she put in place.

“Behave,” she would whisper each morning, working styling cream through the thicket, combing it carefully and plaiting it into two thick braids that fell to the middle of her back. The Mane would look fine when she left for school, but by the time she arrived at her first class, there’d be stray curls sneaking out of the elastic bands and making their way to freedom at the back of her neck and the crown of her head. By lunchtime one or both of the elastic bands would have snapped and the Mane would be a frenzy of tangled curls, foaming and frothing its way down to her waist like it was trying to climb off her body and make a break for freedom. Sometimes, in desperation, she’d tuck her hair underneath her shirt, and she’d spend the rest of the day with its springy, ticklish weight against her back.

It always felt, somehow, like the Mane was laughing at her, whispering that there were better things to do than sit in a classroom learning how to diagram sentences or do long division; that there was a big world out there and that, somewhere in that world, Alice could be happy. Or that she could at least meet a girl who liked her, which was Alice’s fondest wish. In seven different schools, over seven entire years, Alice had failed to make even a single friend.

Alice sighed and squinted, shading her eyes from the glare of the sun as she looked up the street, then down at her luggage. A brown leather trunk, monogrammed in gold, stood at her feet. Two brown leather duffels with the same golden monogram were behind her. There were wheeled brown leather suitcases — one small, one large — to her left and her right.

“This is Quality,” Alice’s mother, Felicia, had said when they’d bought them. Alice could hear the capital Q as Felicia pronounced the word. “They will last your whole life. You’ll use this luggage to go on your honeymoon.”

Right after she’d said the word honeymoon, Felicia had gone quiet, maybe thinking that her bulky, clumsy, wild-haired daughter would never have a honeymoon. When Alice had asked if she could get a purple backpack, Felicia had nodded absently, handed Alice a credit card, and started poking at her phone.

The backpack had a rainbow key chain and a green glow stick clipped to its zipper, pockets full of spare hair bands and a special detangling brush, and secret pockets with stashes of treats. Alice rummaged in a pocket until she found a butterscotch candy. As she unwrapped it she felt the first curl, one at the nape of her neck, spring free.

She sighed. A yellow school bus was pulling up to the corner. Parents were taking pictures, hugging their kids, waving, and even crying as the bus pulled away. Alice wondered how that would feel, having parents who’d wait for the bus with you, who would send you to the local elementary school and maybe even be there when the bus came back.

Alice had started her education at the Atwater School, on New York City’s Upper East Side, where Felicia had gone. At Atwater, the girls wore blue-and-white-plaid jumpers, white shirts, blue kneesocks, and brown shoes, and they sat in spindly antique wooden chairs in small, high-ceilinged classrooms with polished hardwood floors.

In her first week of kindergarten at Atwater, Alice had broken two chairs, torn three uniforms, and wandered away from her class during a trip to the American Museum of Natural History, necessitating emergency calls to her father, Mark, who was in Tokyo at the time, and Felicia, who was in the middle of a massage. The museum guards finally found her asleep around the corner from the diorama of Primitive Man.

“Perhaps she’s more of a hands-on learner,” said Miss Merriweather, the educational consultant her parents had hired after that disaster.

So first grade was at the Barton Academy, in a downtown New York City neighborhood, where the classrooms were painted bright colors and were full of class pets, where the kids had recess three times a day, where they learned to knit and cook in addition to read and spell and add. During her first month at Barton, Alice sat on the class guinea pig, accidentally freed the class turtle, almost impaled her teacher on a knitting needle, and had to be hunted down and dragged out of the climbing structure on the playground every time recess ended.

“Maybe she needs to learn in a different language!” Miss Merriweather had suggested brightly. By then, Felicia had worry lines in the skin at the corners of her eyes, and Mark had gray strands at the temples of his black hair.

During second grade at École Français, Alice came home every day with her crisp white uniform blouse stained with egg yolk or paint or ink or blood. She had trouble sitting still during her lessons and trouble remembering to speak French instead of English. Mandatory ballet class was a disaster best not spoken of. (Alice’s parents agreed not to sue the École for negligence after Alice fell off the stage during a recital; the École agreed not to sue Alice’s parents for the injuries the music teacher, Mademoiselle Léonie, suffered when Alice landed on top of her, not to mention the loss of their piano.)

![635942482342699103-TheLIttlestBigfoot-cvr.jpg [image : 82121254]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/media/2016/03/22/USATODAY/USATODAY/635942482342699103-TheLIttlestBigfoot-cvr.jpg)