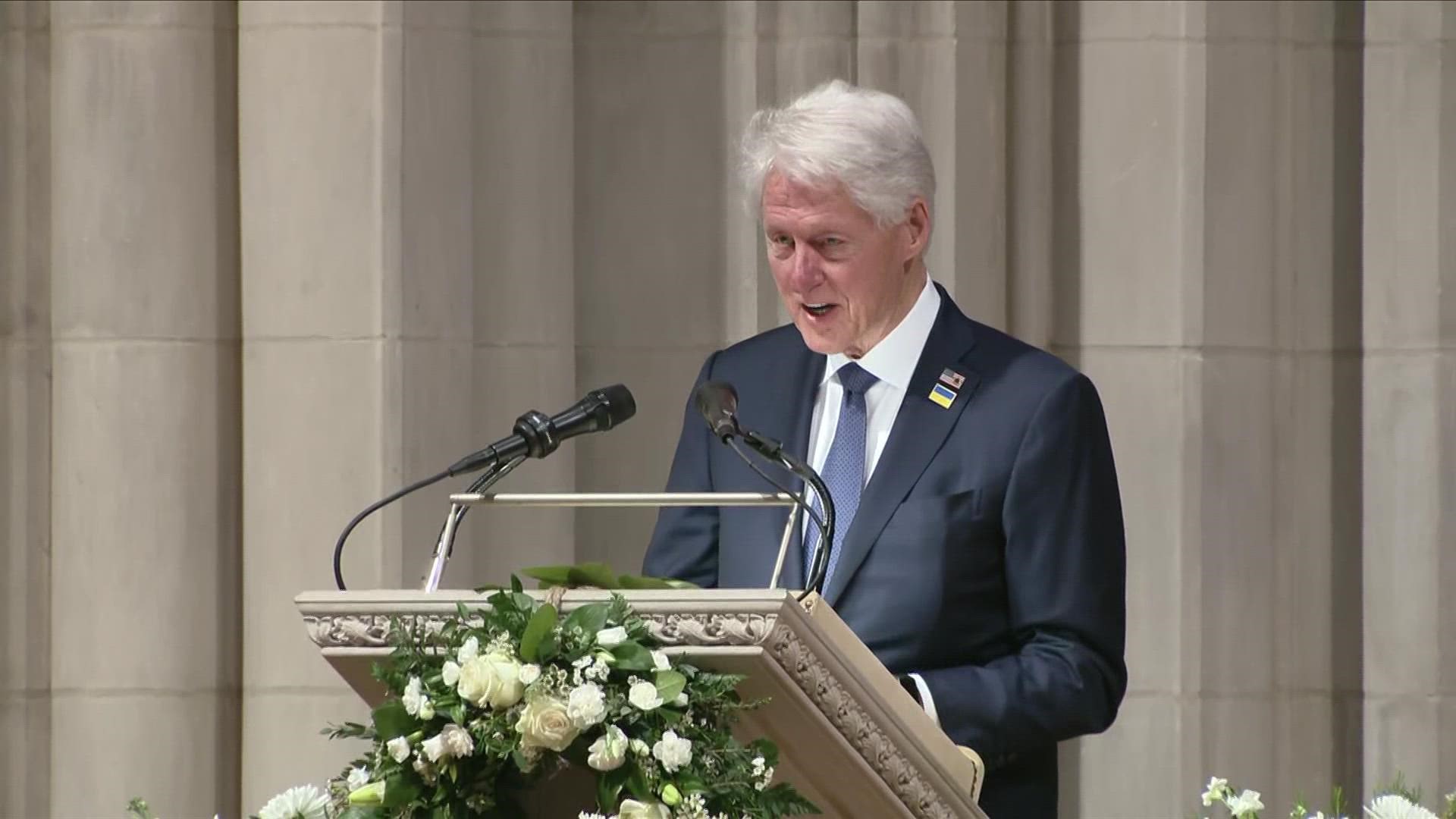

WASHINGTON — Addressing world leaders and America's political elite paying final respects to Madeleine Albright, former President Bill Clinton recalled in his final conversation with the former secretary of state that she didn't want to talk about her declining health at a moment when the West is on edge following Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Albright, Clinton recalled, assured him in that conversation about two weeks before she died last month, that she was getting the best care she could, but didn't want to “waste time” talking about that.

“The only thing that really matters is what kind of world we’re going to leave to our grandchildren," Clinton recalled Albright told him. He added, “She made a decision with her last breath she would go out with her boots on.”

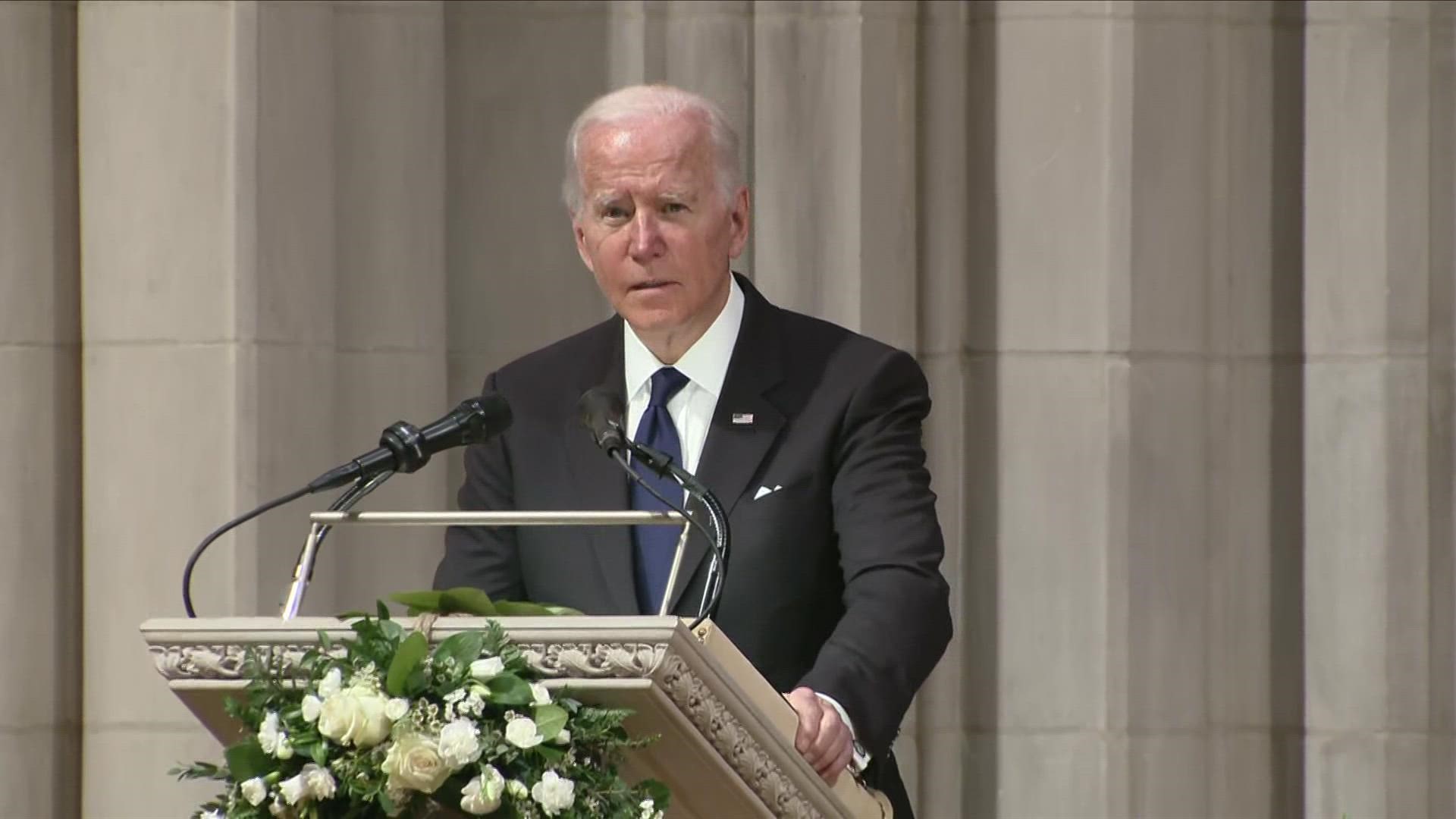

Led by President Joe Biden and former Presidents Barack Obama and Clinton, the man who picked Albright to be his top diplomat and the highest-ranking woman ever in the U.S. government at that time, some 1,400 mourners gathered to celebrate her life and accomplishments of the child refugee from war-torn Europe who rose to become America’s first female secretary of state.

Albright died of cancer last month at age 84, prompting an outpouring of condolences from around the world that also hailed her support for democracy and human rights. Besides the current and former presidents, the service was attended by at least three of her successors as secretary of state along with other current and former Cabinet members, foreign diplomats, lawmakers and an array of others who knew her.

Biden, who delivered a tribute to Albright, said her name was synonymous with the idea that America is "a force for good in the world.”

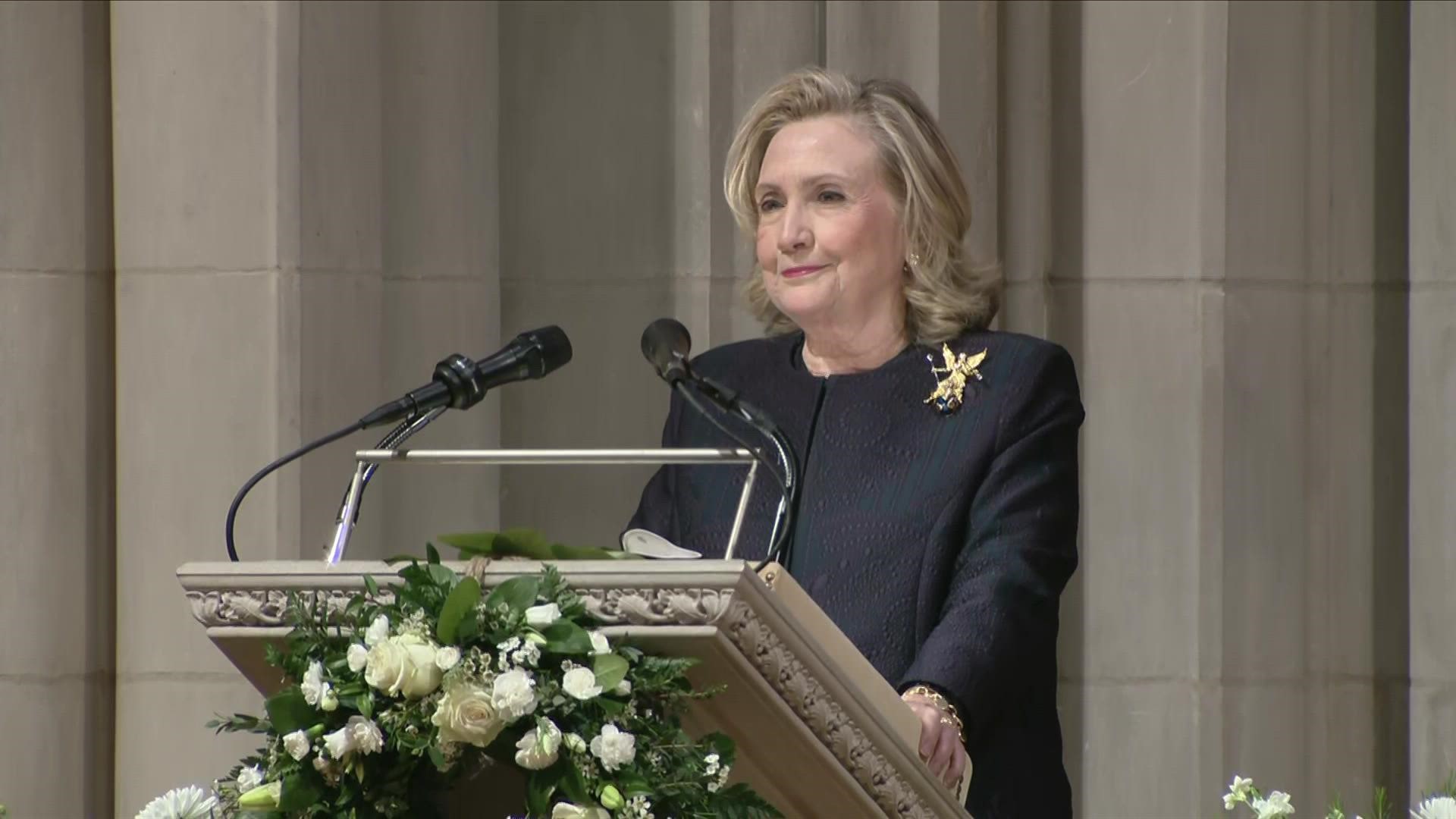

Hillary Clinton urged her husband to tap Albright to serve as secretary of state, a role that Clinton would serve in herself during the Obama administration. The two developed a strong friendship over the years.

Clinton in her own tribute recalled some lighter memories of Albright, including the time she taught the foreign minister of Botswana the Macarana and danced the night away with a young, handsome man at her daughter Chelsea's wedding. She also remembered Albright as a fearless diplomat that broke barriers and then counseled, cajoled and inspired women to follow in her footsteps.

“The angels better be wearing their best pins and putting on their dancing shoes,” Clinton said. “Because if as Madeleine believed there’s a special place in hell for women who don’t support other women, they haven’t seen anyone like her yet.”

The crowd that gathered at Washington National Cathedral to honor Albright included the current secretary of state, Antony Blinken, and former secretaries Condoleezza Rice and John Kerry were slated to attend. Other top current officials expected to be present included Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, CIA Director Bill Burns, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Gen. Mark Mark Milley and White House national security adviser Jake Sullivan. The members of the VIP audience were masked, as Albright's family had requested.

Foreign dignitaries invited to the funeral included the presidents of Georgia and Kosovo and senior officials from Colombia, Bosnia and the Czech Republic.

Albright was born in what was then Czechoslovakia, but her family fled twice, first from the Nazis and then from Soviet rule. They ended up in the United States, where she studied at Wellesley College and rose through the ranks of Democratic Party foreign policy circles to become ambassador to the United Nations. Bill Clinton selected her as secretary of state in 1996 for his second term.

Although never in line for the presidency because of her foreign birth, Albright was near universally admired for breaking a glass ceiling, even by her political detractors.

As a Czech refugee who saw the horrors of both Nazi Germany and the Iron Curtain, she was not a dove. She played a leading role in pressing for the Clinton administration to get involved militarily in the conflict in Kosovo. “My mindset is Munich,” she said frequently, referring to the German city where the Western allies abandoned her homeland to the Nazis.

As secretary of state, Albright played a key role in persuading Clinton to go to war against the Yugoslav leader Slobodan Milosevic over his treatment of Kosovar Albanians in 1999. As U.N. ambassador, she advocated a tough U.S. foreign policy, particularly in the case of Milosevic’s treatment of Bosnia. NATO’s intervention in Kosovo was eventually dubbed “Madeleine’s War.”

She also took a hard line on Cuba, famously saying at the United Nations that the 1996 Cuban shootdown of a civilian plane was not “cojones” but rather “cowardice.”

Former President Clinton recalled the moment in his tribute, remembering that Albright faced criticism at the time that the sharp barb was “undiplomatic” and “unladylike." He absolutely loved it.

“I called her and I said ... 'This is the best line developed and delivered by anybody in this administration," Clinton said.

In 2012, Obama awarded Albright the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, saying her life was an inspiration to all Americans.

Born Marie Jana Korbel in Prague on May 15, 1937, she was the daughter of a diplomat, Joseph Korbel. The family was Jewish and converted to Roman Catholicism when she was 5. Three of her Jewish grandparents died in concentration camps.

Albright was an internationalist whose point of view was shaped in part by her background. Her family fled Czechoslovakia in 1939 as the Nazis took over their country, and she spent the war years in London.

After the war, as the Soviet Union took over vast chunks of Eastern Europe, her father brought the family to the United States. They settled in Denver, where her father taught at the University of Denver. One of Korbel’s best students was Rice, who would later succeed his daughter as secretary of state.

Albright graduated from Wellesley College in 1959. She worked as a journalist and later studied international relations at Columbia University, where she earned a master’s degree in 1968 and a Ph.D. in 1976. She then entered politics and what was at the time the male-dominated world of foreign policy professionals.