WASHINGTON — The federal government declared a public health emergency Thursday to bolster the response to the monkeypox outbreak that has infected more than 7,100 Americans.

The announcement will free up money and other resources to fight the virus, which may cause fever, body aches, chills, fatigue and pimple-like bumps on many parts of the body.

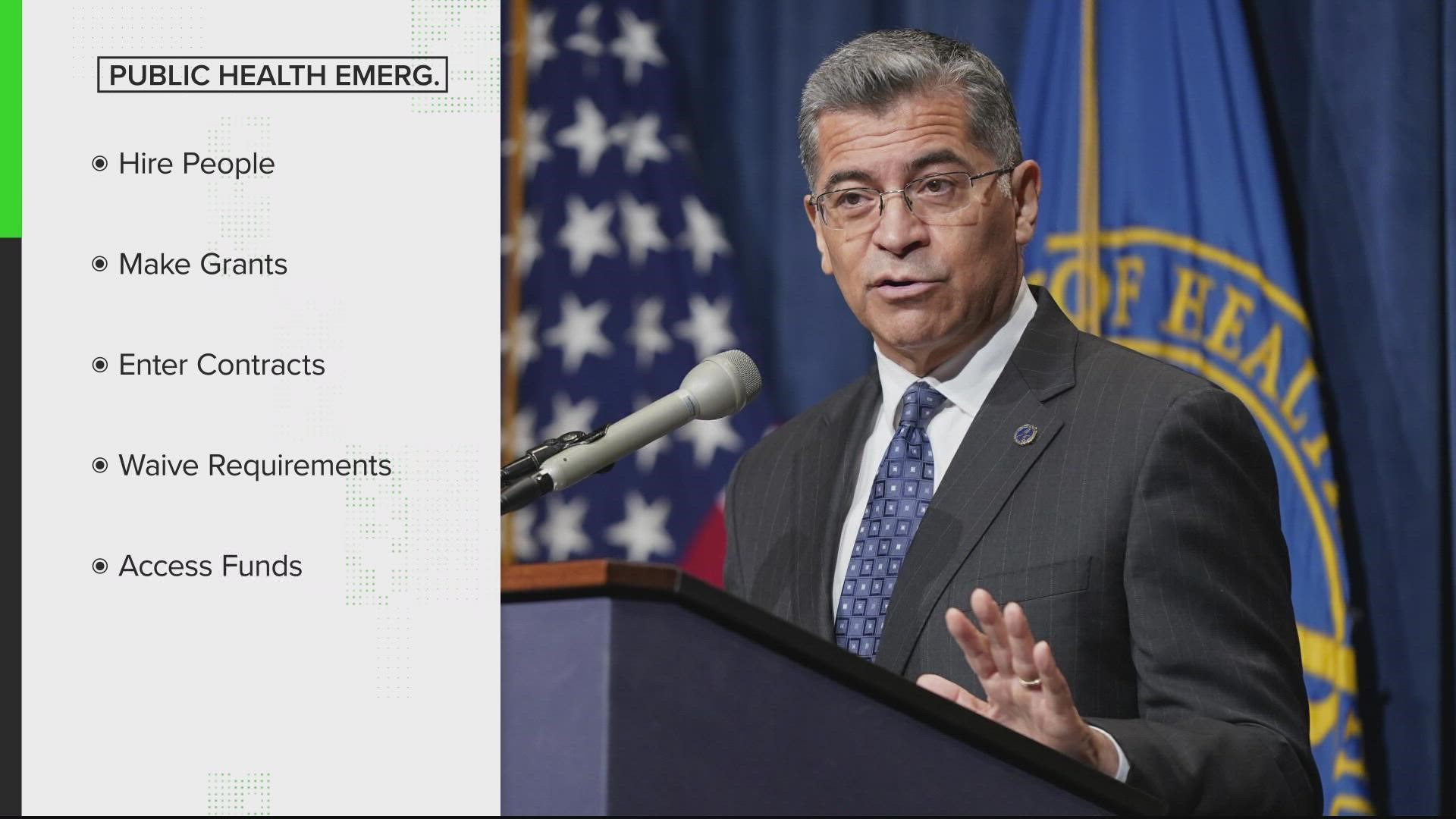

“We are prepared to take our response to the next level in addressing this virus, and we urge every American to take monkeypox seriously,” said Xavier Becerra, head of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The declaration by HHS comes as the Biden administration has faced criticism over monkeypox vaccine availability. Clinics in major cities such as New York and San Francisco say they haven’t received enough of the two-shot vaccine to meet demand, and some have had to stop offering the second dose to ensure supply of first doses.

The White House said it has made more than 1.1 million doses available and has helped to boost domestic diagnostic capacity to 80,000 tests per week.

The monkeypox virus spreads through prolonged skin-to-skin contact, including hugging, cuddling and kissing, as well as sharing bedding, towels and clothing. The people who have gotten sick so far have been primarily men who have sex with men. But health officials emphasize that the virus can infect anyone.

No one in the United States has died. A few deaths have been reported in other countries.

Earlier this week, the Biden administration named top officials from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to serve as the White House coordinators to combat monkeypox.

Thursday's declaration is an important — and overdue — step, said Lawrence Gostin, a public health law expert at Georgetown University.

“It signals the U.S. government’s seriousness and purpose, and sounds a global alarm,” he said.

Under the declaration, HHS can draw from emergency funds, hire or reassign staff to deal with the outbreak and take other steps to control the virus.

For example, the announcement should help the federal government to seek more information from state and local health officials about who is becoming infected and who is being vaccinated. That information can be used to better understand how the outbreak is unfolding and how well the vaccine works.

Gostin said the U.S. government has been too cautious and should have declared a nationwide emergency earlier. Public health measures to control outbreaks have increasingly faced legal challenges in recent years, but Gostin didn’t expect that to happen with monkeypox.

“It is a textbook case of a public health emergency,” Gostin said. “It’s not a red or a blue state issue. There is no political opposition to fighting monkeypox.”

A public health emergency can be extended, similar to what happened during the COVID-19 pandemic, he noted.

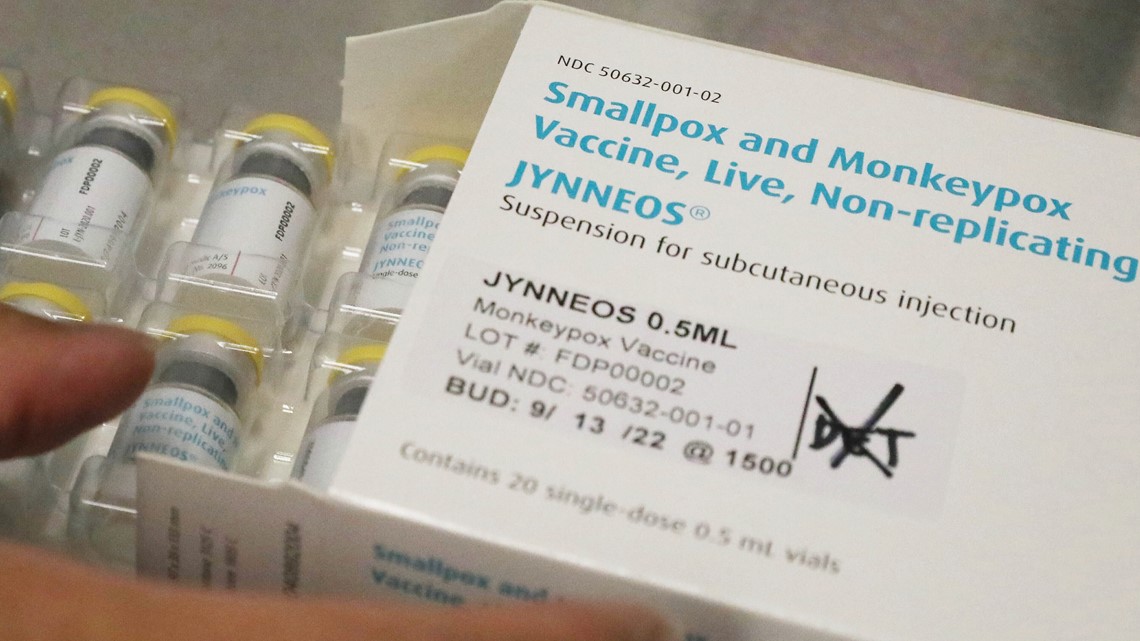

The urgency in the current response stems from the rapid spread of the virus coupled with the limited availability of the two-dose vaccine called Jynneos, which is considered the main medical weapon against the disease.

The doses, given 28 days apart, are currently being given to people soon after they think they were exposed, as a measure to prevent symptoms.

Becerra announced the emergency declaration during a call with reporters. During the call, Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Robert Califf said regulators are reviewing an approach that would stretch supplies by allowing health professionals to vaccinate up to five people — instead of one — with each vial of Jynneos.

Under this so-called “dose-sparing” approach, physicians and others would use a shallower injection under the skin, instead of the subcutaneous injection currently recommended in the vaccine’s labeling.

Califf said a decision authorizing that approach could come “within days.”

That would require another declaration, to allow the government to alter its guidelines on how to administer the vaccine, officials said.

Health officials pointed to a study published in 2015 that found that Jynneos vaccine administered that way was as effective at stimulating the immune system as when the needle plunger deeper into other tissue.

But experts also have acknowledged they are still gathering information on how well the conventional administration of one or two full doses works against the outbreak.

Others health organizations have made declarations similar to the one issued by HHS.

Last week, the World Health Organization called monkeypox a public health emergency, with cases in more than 70 countries. A global emergency is WHO’s highest level of alert, but the designation does not necessarily mean a disease is particularly transmissible or lethal.

California, Illinois and New York have all made declarations in the last week, as have New York City, San Francisco and San Diego County.

The declaration of a national public health emergency and the naming of a monkeypox czar are “symbolic actions,” said Gregg Gonsalves, a Yale University infectious diseases expert.

What’s important is that the government is taking the necessary steps to control the outbreak and — if it comes to that — to have a plan for how to deal with monkeypox if it becomes endemic, he said.

Monkeypox is endemic in parts of Africa, where people have been infected through bites from rodents or small animals. It does not usually spread easily among people.

But in May, a wave of unexpected cases began emerging in Europe and the United States. Now more than 26,000 cases have been reported in countries that traditionally have not seen monkeypox.

What does a federal public health emergency declaration do?

A Public Health Emergency Declaration is made by the secretary of Health and Human Services—in this case, Xavier Becerra.

“It would allow HHS to instantaneously do some things that it can't presently do quickly," James Hodge, law professor at Arizona State University said to WUSA9.

It enables Bacerra to hire people, make grants, enter contracts, waive certain requirements and access additional funds, for example.

“Usually during emergency declarations, like with opioids or things we've seen in the past, there actually would be a free standing fund ready to be used for devoting to these purposes," Hodge said. "We've been working to refill that fund post-COVID, and to my knowledge, to date, it's not yet been refilled."

He continued, "In fact, Congress has been reticent to do it. Now, monkeypox may change its mind very quickly. But the sheer fact is, the funds that normally would be there, to the tune of millions of dollars, simply may not be at this point in time.”

What are the symptoms of monkeypox?

The symptoms tend to overlap with those of most viruses. Fevers, headaches, chills, muscle aches, exhaustion and swollen lymph nodes are all symptoms of monkeypox. The true indicator that distinctly separates it from the rest is a pimple-like rash that appears on the face and other parts of the body, according to the CDC.

"The symptoms of monkeypox are very much like the symptoms of a cold initially," said Dr. Payal Kohli, assistant clinical professor at the University of Colorado. "So if you've got fevers, exhaustion, chills, a rash with or without swollen lymph nodes, you have to have a pretty high concern that it could potentially be monkeypox."

Symptoms may vary from person to person, and the rashes can appear at different stages and typically last 2-4 weeks. Some people tend to get rashes first and then symptoms, but others might just get a rash.

The CDC recommends monitoring temperatures twice a day if exposed to someone with monkeypox as well as keeping an eye for other symptoms. Once symptoms develop, immediate isolation is recommended.

Here is the full list of symptoms according to the CDC:

- Fever

- Headache

- Muscle aches and backache

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Chills

- Exhaustion

- Respiratory symptoms, such as a sore throat, nasal congestion or cough

- A rash that can look like pimples or blisters that appears on the face, inside the mouth, and on other parts of the body, like the hands, feet, chest, genitals, or anus.

WUSA's Eliana Block contributed to this report.