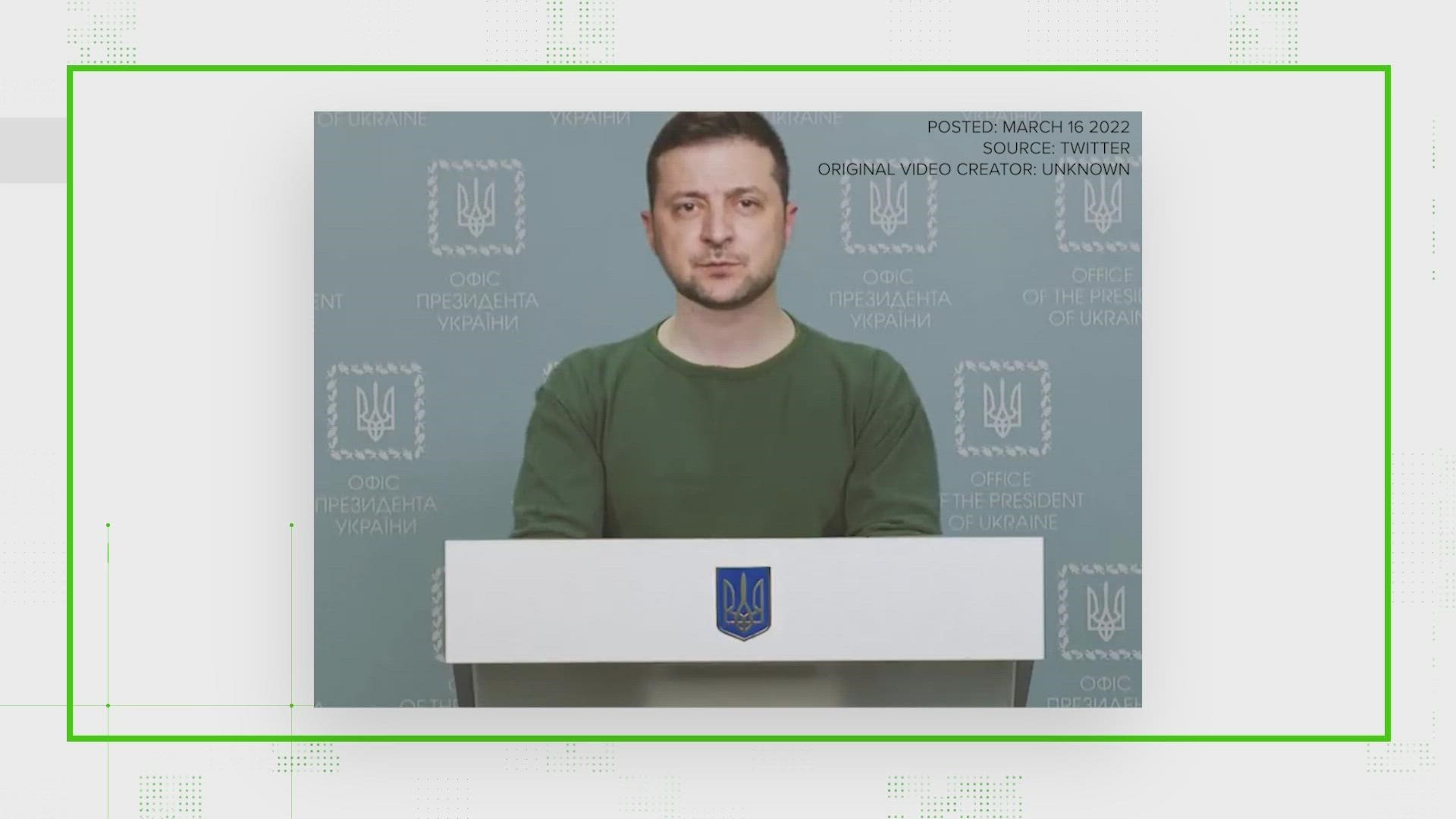

WASHINGTON — Last week, a video of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy began making the rounds on social media. Like many of his other recent appearances, the video featured him in his familiar green t-shirt and a generic backdrop.

But this was different in two ways. First, it was a video of Zelenskyy telling the country that he had surrendered to Russia after three weeks of fighting off their invasion. And second, the video was fake.

In reality, the video was a "deepfake" meant to fool Ukrainian troops and sow confusion in the country. While it's not a certainty that the Russian government is behind the video, Ukrainian intelligence agencies warned earlier in the month that this exact video would be coming out, saying nobody should believe any videos of Zelenskyy surrendering.

Different versions of the video were uploaded across the internet, racking up hundreds of thousands of views.

Broadcasts from Ukrainian news channels Ukraine 24 and Today were also hacked to show the fake surrendering video. But despite the effort to spread the video, it didn't get a lot of traction.

The video was quickly flagged by fact-checkers including the Verify team and removed from major social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter.

RELATED: No, the video of Ukrainian President Zelenskyy urging surrender isn’t real. It’s a deepfake

One of the reasons the Zelenskyy video didn't get much traction: it wasn't a particularly good deepfake.

In the video, the fake Zelenskyy is stiff, blinking in a way that isn't quite natural and only moving his head.

According to John Bullock, an Associate Professor of Political Science and a Fellow at the Institute for Policy Research at Northwestern University, tells like that are the easiest way to tell if something is a deepfake.

"No one seems to be fooled by the video," he said. "That's very likely because they already know of Zelenskyy, they've been watching real recordings of Zelenskyy for the past few days."

How to tell if it's a fake

Bullock pointed to several things viewers can watch for to determine if a video is a deepfake, or has been manipulated in some other way.

Blinking is often "often a dead giveaway," Bullock said, because faking realistic blinking is difficult and people notice when it is slightly off.

Posture is the second thing to look for. "If somebody's sitting absolutely still, people just don't do that in real life," Bullock said.

Speech can often give clues that the words aren't coming naturally, Bullock said. "Even the best-spoken people will intersperse 'um' and 'uh' into their speech. Sometimes that'll be missing."

Body movement is another area where it's easy to notice something wrong. If a speaker's body doesn't move with their head, or looks disjointed, it can be a sign of manipulation.

Shadowing can often be a tell that fake video creators forget about. "Sometimes the shadows are just in the wrong places," Bullock said.

While this checklist is a quick way of determining whether video is manipulated, it's not foolproof. And experts warn within a few years it could be obsolete entirely.

Deepfake technology relies on AI and machine learning to create what is essentially a realistic special effect. As the technology improves and the AI computers behind the deepfakes become more sophisticated, the tells Bullock watches for could become more subtle or disappear entirely.

"Those problems are all going to be going away in five years," he said. "So this is going to be a very big problem within a decade."

Why is this deepfake so bad?

Deepfake videos have evolved since their introduction in the 90s, especially as rapid improvements in AI technology within the past decade have made it easier to produce them.

But to many experts, this Zelenskyy deepfake is just poorly put together.

"The really professional ones you've seen, they use a lot of video, a lot of high definition cameras," said Nicholas Mattei, an Assistant Professor of Computer Science at Tulane University.

Mattei studies the theoretical and practical uses of AI technology as well as the ethics behind them.

"It's surprising on some level because there's a lot of video of Zelenskyy out there," he said. "Zelenskyy was on a TV show. There's tons of video. You have to think they had enough data to do this better."

He pointed to a similar "fake news" example from World War II, when the Axis Powers printed up flyers saying the Allies had surrendered. Those lying leaflets were riddled with typos.

There's no clear explanation as to why this video has such obvious tells that it's fake. Bullock hypothesized that it could be because the Russian government underestimated people's ability to distinguish the real video from fakes.

It could also have been an independent actor to have made the video.

"I wouldn't be surprised if it is (Russia), but this type of technology is absolutely within the hands of independent actors as well," Bullock said. "Which is another thing that makes this perhaps even more scary."

The future of disinformation

While the concept of deepfake videos isn't new, the Zelenskyy video appears to be the first time one has been used in the context of a war.

Sam Gregory, the program director at human rights and technology group Witness, told Euronews that the use of fake video in this way is unprecedented.

"This is the first time we have seen a really significant perceived threat of deepfakes that can be anticipated in a conflict," he told the outlet.

Bullock said it wasn't surprising to him that the Russian government would (allegedly) deploy fake videos given their track record of spreading a wide net of false information about a variety of subjects.

"The Russian government has been savvy and has taken advantage of the advent of social media and the popularity of social media to spread disinformation," he said. "And to make a concerted effort to spread misinformation in ways that weren't true during the Cold War."

But now that the proverbial genie is out of the bottle, it's likely impossible to put it back in. With the technology to create deepfakes in the hands of amateurs and state actors alike, they will likely become more prevalent.

"That is going to happen, and it is going to happen sooner than we think. And that is the great problem," Bullock said. While major organizations like news outlets might be able to hire experts or use technology to determine authenticity, "you're not going to be seeing this on YouTube or Tik Tok at all, which is where more and more people are getting their news."

Mattei pointed to the plethora of misinformation already at home on the internet as an example of how this could shape information in the future.

You can't believe everything you read," he said. "I think more and more it's going to be a truism that you can't believe everything you see."

Should you be scared?

The increased use of fake videos seems like a problem more for celebrities and politicians than the regular person.

Mattei said as deepfake technology becomes easier to use, it could trickle down.

"It's one of these things where the cat's out of the bag on how to do this in the first place. So you can't really put that back," he said.

For example, news outlets would likely report on a fake video of a politician, but won't be able to do the same for more personal cases.

"Those kinds of institutional reliance works well for something like that, for a famous person or (if) it's a president, or something of national interest," he said. "What happens if somebody deepfakes a video of you saying something crazy in a meeting?"

If that happens, people won't be able to rely on institutional verification to determine if it's fake.

"I think that's really the fundamental question of a lot of this technology," Mattei said. "It's that it democratizes power to make these videos, and a lot of time we think that democratizing power is a good thing. This is an example where it could be a bad thing."

As the technology becomes more prevalent, it's a question he said more researchers and developers will have to wrestle with, especially in the aftermath of this new use for deepfake technology.

"I think that's the central ethical question for technology folks as we grow and build and distribute these tools very quickly," he said.

Why use deepfakes

To the average person, deepfake videos are associated with misinformation. News stories about their use during the 2016 and 2020 election cycles painted them as tools used to smear political candidates — with U.S. intelligence agencies alleging that Russia used them to interfere with the campaign process.

There is also growing concern that they could be used to create NSFW content featuring somebody without them ever being aware, including celebrities.

But according to experts, the technology isn't purely an evil designed to trick people.

It can have uses ranging from entertainment to legitimate scientific research.

Forward-thinking researchers believe celebrities will be able to license their deepfake likeness to films, allowing them to be in a movie without ever being on set. They could also reduce the need to reshoot scenes and work around a star's busy schedule.

It can also be used to resurrect the dead.

In several high-profile cases, the technology has been used to create fake versions of people who have died to convey a message.

In 2020, Kim Kardashian posted a video of her late father, Robert Kardashian, created with deepfake technology for her birthday.

The same year, Joaquin Oliver, one of the victims of the Parkland mass shooting, was resurrected as a deepfake with the blessing of his parents to advocate for a gun-safety campaign urging people to vote.

Social scientists have also used deepfakes to gain insights into human perceptions of race, identity and gender.

What are the solutions

Given the number of reasons to use deepfakes, it's unclear what kind of solution could help or if anything would be more than a bandage against the flood of misinformation they can produce.

Both Bullock and Mattei said it was important to train people on how to spot fake videos, but acknowledged that identifying them was an uphill battle.

Most people have no training in this sort of detection, and even with training, it's going to get harder and harder," Bullock said. "It's going to become harder and harder to distinguish fake videos from the real thing (by looking at them).

Another solution is legislative. Even with the many uses of deepfake technology, Bullock said legislators may eventually have to confront the problems associated with it head on. A ban on the use of deepfake videos could starve many opportunities for them to be used by bad actors.

"I suspect that the trade off would be worth it," Bullock said. "There are legitimate academic reasons to use these videos. But the hazards of the the technology are so great that a widespread ban, perhaps even extending to an academic ban, might be reasonable."

But making the use or creation of a deepfake a crime isn't going to solve the problem permanently.

Both world powers and teenagers with cell phones have access to the technology, and it would be impossible to punish creators internationally.

"Of course, even the most restrictive law is not going to stop all of these deepfakes," Bullock said. "Russian operatives are not going to care if it's banned in America."

Instead, both researchers conceded that one of the most likely solutions was a kind of digital arms race. As deepfake technology becomes harder to detect, some computer science researchers are developing tools to identify the manipulated videos.

"I think it's going to be an escalating arms race to better fake videos and then better detectors for those fake videos, information campaigns and disinformation campaigns," said Mattei. "I think that that's unfortunately the state of the world that we're in.

Will there ever be an end to the technological battle over fake videos once it begins in earnest?

"I don't know if there's an endpoint," Mattei said. " I would hope so. I would hope there's an endpoint ... but I doubt there's a fix for it, personally."