SEATTLE — A new push to get hazardous RVs and cars off Seattle streets has some of the people living in those vehicles concerned.

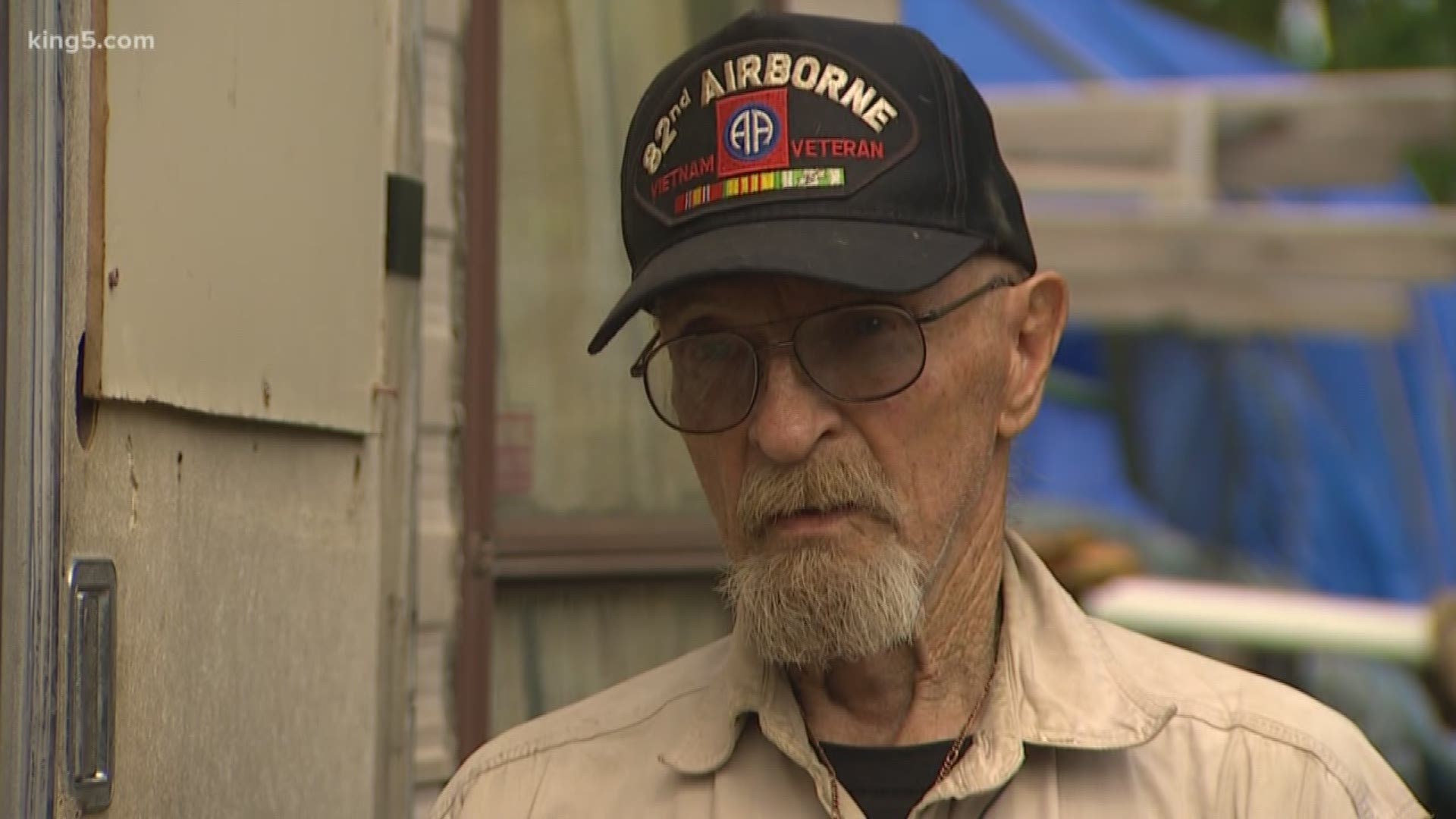

Larry Huffman is a Vietnam veteran, now staying in a camper with his dog Bull in Seattle’s SODO neighborhood.

“To get in a small, dilapidated, junky studio apartment in Seattle is over $1,000,” Huffman said. “What does that leave you to live on? Nothing.”

Huffman said the amount he collects from social security just doesn’t cover much more. He’s been out on the streets for a few years, not by choice, but a necessity.

“I want off the streets,” he said. “I’m 75 years old. I don’t have much time left in my life. Maybe I do, maybe I don’t, you don’t know. But I want off the streets. I don’t want to be here.”

Huffman keeps the RV hitched to his pickup truck for fear of it being towed. Stoking those fears is the word that the city will begin applying public health criteria to campers like his.

Mayor Jenny Durkan announced Wednesday new steps in an effort to stem the supply of hazardous vehicles. If vehicles towed by a city contractor meet the state definition of a public health hazard, it will be destroyed, not re-sold.

Durkan also plans to transmit legislation that updates the city code to fine predatory landlords who rent junk cars and vehicles to vulnerable populations.

The legislation will require remediation of up to $2,000 which will go into a restitution fund for vehicle occupants, city officials said.

“We have an obligation to protect public health and ensure that our neighbors are not living in inhumane conditions. And we will hold accountable those who prey on vulnerable people for profit,” said Durkan. “We will continue to work for holistic solutions and do more to connect people with services and housing – and we will continue to invest in the strategies we know have an impact, like our Navigation Team.”

Huffman worried how that health standard would be applied.

“You only can get what you can get,” he said. “We can’t afford to buy one like that sitting over there. You’ve got to have something. And if you’re paying $200-300 for one, it’s not going to look real good.”

Durkan’s office said the push is to make sure people don’t live in inhumane conditions. Huffman doesn’t see other options.

“They’re concerned more about what it looks like than the health and welfare of the individual that’s in it,” Huffman said.

A few blocks away, Troy Arnette echoed those concerns.

“What good does it do to put somebody back on the street, on a sidewalk with nothing,” Arnette said. “Does nobody no good. Does the city no good, does us no good.”

Despite working, Arnette said he still can only afford to stay in a camper. He knows it isn’t pretty and empathized with homeowners concerned by the appearance of the vehicles. But it’s all he’s got.

“Don’t judge a book by its cover,” he said. “There’s a lot of good people out here homeless like me. People that go to work, and don’t steal from them. We do have to have somewhere to go.”

"Some of these motor homes I've seen probably should probably be in a junkyard," said Huffman. "But if it's the only house you've got, what are you going to do? This ground is not comfortable."