SEATTLE — A 2018 law makes more veterans eligible for mental health treatment, but the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs has done little to spread the word about the program.

Answering increased concern about suicides by veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, Congress ordered the VA to open up care to a class of veterans who previously were largely ineligible: veterans who left the service with an other-than-honorable discharge.

The 2018 change expanded a June 2017 VA program that opened the door for other-than-honorable veterans to receive VA mental health care for up to 90 days in emergencies. Under the new law, certain veterans can receive ongoing mental health treatment, and they don't have to be in crisis to qualify.

The VA estimates there are 500,000 veterans in the U.S. with an other-than-honorable discharge. Yet, less than one percent of that population received treatment at the VA in each of the last two years, according to data the agency provided.

“Veterans are dying because they do not know they are eligible for mental health care. That should be a national shame everyone is aware of," said Kristofer Goldsmith, the associate director for policy and government affairs at Vietnam Veterans of America. "The VA’s outreach to this target population is abysmal.”

Other-than-honorable discharges are usually issued when a veteran is separated from the military for misconduct. The discharge status automatically strips away a veteran’s right to VA benefits, but the agency has a separate process to make exceptions for veterans whose misconduct was triggered by PTSD, other service-related trauma, or other unique circumstances.

That process can sometimes take longer than a year, which experts say is too long for the veterans struggling right now. It’s one reason why advocates and lawmakers pushed for the legislation to increase access to mental and behavioral health care.

Last year, the VA treated 2,850 other-than-honorable veterans across the U.S., according to an agency spokeswoman. In 2017, VA officials treated 940 people with an other-than-honorable discharge. Both years, about 70 percent of those veterans were seen for mental health services.

In Washington state, 46 other-than-honorable veterans received VA treatment last year. According to the provided data, 16 of those people received mental health treatment. In 2017, 20 people with an other-than-honorable discharge got treatment at Washington VA medical centers. Five of those people received mental health treatment.

It’s not immediately clear how many of the other-than-honorable veterans reflected in the VA's data received care under the 90-day emergency mental health care policy or the 2018 law because a national VA spokesman said the agency doesn’t have the capability to separate it.

It's also unclear if more other-than-honorable veterans have received mental health treatment at the VA so far this year. The VA ignored KING 5's repeated requests for this information.

But lawyers, doctors, and advocates who work with other-than-honorable veterans say with certainty that many who are eligible for mental health care still don't have a clue they qualify.

"Even if there was good intent behind the law, it's lacking the core aspect of implementation to actually make it a benefit to veterans," said Rose Goldberg, supervising staff attorney at Swords to Plowshares, a San Francisco advocacy group that offers legal support to veterans with less-than-honorable discharges. "I have yet to have a client who has learned of this program him or herself."

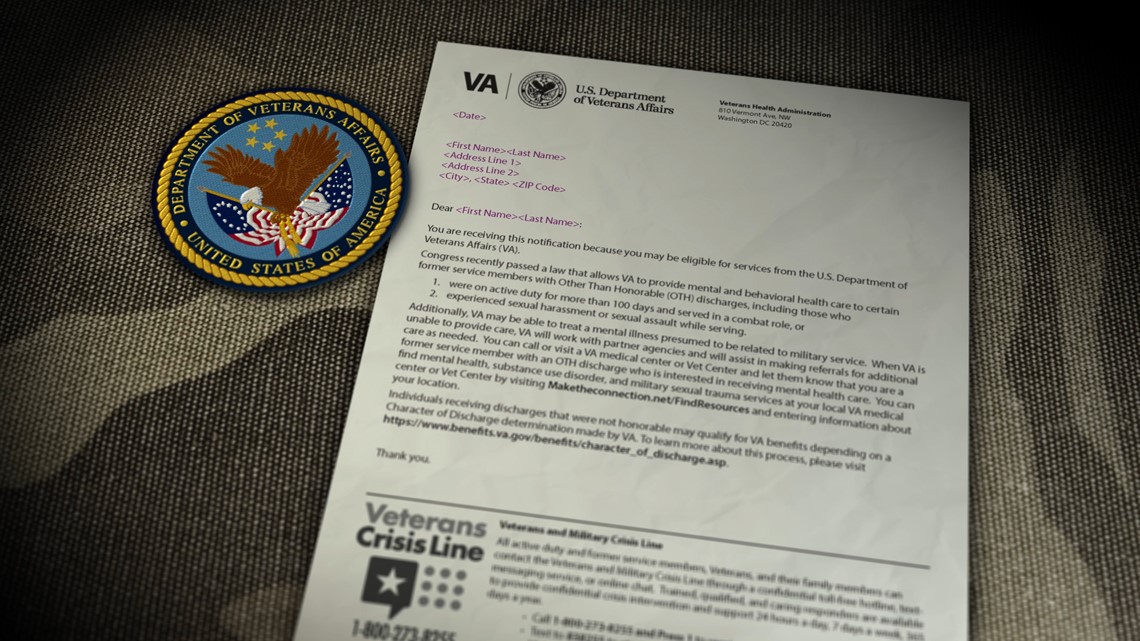

VA officials had 180 days after the law took effect in March 2018 to notify veterans who became eligible for mental health care. But instead, it took the agency nearly a year to inform veterans of the change. They did so by sending out 477,404 letters to veterans in January 2019, according to a VA spokeswoman.

It was the first time VA officials took a step to directly notify other-than-honorable veterans who were eligible for mental health care. Prior to that, the agency issued press releases, public statements and social media posts to inform veterans of the 2017 policy that opened the door to short-term, emergency mental health treatment.

While the letter is an improvement to the past, advocates say it's not a sufficient way to reach this population. They say many of these veterans are now homeless as a consequence of their discharge status and the VA needs to do more leg work to find them.

"There are veterans who don't have mailing addresses, don't have e-mail addresses, don't have phone numbers —who are among those who are literally in the greatest need of VA services," Goldsmith said. "The VA seems to have abdicated its responsibility in terms of notifying these people that they are eligible."

Robert Stanulis, a Portland neuropsychologist who treats veterans with less-than-honorable discharges, said he's shocked to see the lack of outreach to these veterans, given the fact that they face a greater risk of suicide when they're not treated within the VA system.

"Why are we not treating it like we would if it was a public emergency?" he said. "There would be billboards up. It'd be on TV. It'd be on radio. It would be inescapable."

Jeremiah Beck, an Everett veteran who was discharged from the Navy under other-than-honorable conditions in 2005, said he never received a letter from the VA about the changes. The veteran said the VA determined years ago that he didn't qualify for benefits, including health care.

"It's irritating actually. If I would have known about this (law change) earlier, I would have started fighting again (for VA mental health care)," he said.

Bran McIan, who was discharged from the Army under other-than-honorable conditions in February, said he didn't learn that he was eligible for mental health care until he was contacted by KING 5 in April. The former special forces medic who served for more than nine years suffers from PTSD and is seeking treatment.

"There have been times when I've literally been punching my steering wheel and screaming at the top of my lungs in my truck because I'm just so set off by things," McIan said. "That's the price I pay to be able to function in society without any treatment."

'We obviously need to be doing more'

Locally, VA officials say they're willing and eager to treat more other-than-honorable veterans who need mental health care, adding that mental health staff would never turn away someone in crisis.

But Jesse Markman, acting associate chief of staff for mental health at VA Puget Sound Healthcare System, admits more outreach is needed.

“Do I think we are working hard and trying to do the best we can? I do,” he said. “And would I say we’re doing enough? No, I mean the numbers speak for themselves. We obviously need to be doing more and we can always work harder on doing more (to reach veterans).”

KING 5 asked for specific examples of actions Puget Sound VA officials took to directly reach more veterans who may be eligible for mental health care under the policy and what they plan to do to reach more people in the future. Tami Begasse, the public affairs director at VA Puget Sound,Medical Center, did not respond.

National VA officials declined multiple requests for an interview to discuss this issue. They did not respond to questions about whether the agency is planning additional direct outreach or taking other steps to improve the failures advocates and veterans have identified.

Advocates call for more training

VA spokesman Terrence Hayes said staff at all VA facilitates have received training on the March 2018 law. He said training included national presentations for regional and facility leadership, mental health leadership and eligibility office staff.

But veteran advocates say the VA needs to do a more thorough job of training its front-line employees on the new law because one confusing interaction can deter a veteran from returning to seek help.

"Even though the VA is a multi-armed beast, one untrained person sitting at a desk is speaking for the VA in the veteran's eyes," Goldberg, the Swords to Plowshares attorney, said.

KING 5 accompanied McIan, the former special forces medic, on an April trip to American Lake VA Medical Center in Tacoma to observe how staff interacted with him when he sought treatment for PTSD.

The veteran told the intake specialist at the eligibility counter that he wanted to see a professional for mental health. She tried to help him, but she gave him the wrong information twice before finding an e-mail from her boss about the new law.

Still, she struggled to explain it.

"(She told me) three different things on one issue. It was only mental health care, and I still got three different answers," McIan said. "If I had gone there on my own and got the answers I got, I probably would not be going back."

After learning in April of the veteran's confusing encounter, the chief of the eligibility enrollment and benefits office at VA Puget Sound said he would re-educate his staff on the new law. To date, local VA officials have not confirmed if the additional education occurred.

"We're always committed to any opportunity to better communicate," Begasse, the VA Puget Sound public affairs director, said. "Veterans should know that if they are other-than-honorable, they can walk through our doors. We are here to help them navigate that."

Mental health care only a small step

Veteran advocates say they are pleased that Congress took a step to increase access to mental health care for veterans with other-than-honorable discharges. But they say more action is needed to get those veterans the help they deserve.

"I think it's a very small step in the right direction but I would hope that it doesn't have the bad consequence of people thinking that because there's been one improvement, that the push for change should slow down," Goldberg said.

Other-than-honorable veterans who are now eligible for mental health care under the law don't necessarily qualify to have other medical issues treated, unless those issues are connected to their mental health problem. They also are not automatically eligible for other benefits, like disability compensation, VA housing programs or the GI Bill.

"It doesn't allow them to get the rest of what mental health care involves: a disability rating. Remember, many of these people are totally disabled from work. So what good does it do you if you get mental health care if you can't pay the rent?" Stanulis, the neuropsychologist, said. "I'm going to do better with you and your PTSD when I can also put you in vocational rehabilitation, when I can get you into housing, when I can treat you as a whole person. We know we have better outcomes."