SEATTLE — Since the early 1990s, scientists up and down the West coast have known about a mysterious killer lurking in the waters of urban creeks wiping out populations of Coho salmon.

THE PROBLEM

While it is natural to see dead Coho salmon in urban creeks, they are supposed to die after they spawn.

In fact, their deaths may have gone unnoticed without the help of park rangers, organizations and citizen scientists who help track Coho salmon populations.

It wasn't until the fish was cut open that people realized these salmon were dying before they spawned, causing a ripple effect in our environment.

In a healthy ecosystem, salmon provide food for orcas and spawn in urban creeks. Their decomposing corpses also provide nourishment for soil and forests.

It's this critical role that led scientists on a journey of searching for the mystery killer and one that ended in western Washington.

THE DISCOVERY

In 2014, the University of Washington Tacoma Center for Urban Waters brought in researcher and professor Ed Kolodziej to help lead a team of scientists tasked with solving the mystery.

With the help of local communities, Kolodziej’s team was able to collect water samples from urban creeks seeing high pre-spawn mortality rates.

“We were seeing lots of tire chemical in water for years and by 2017 our investigations pointed to tire,” Kolodziej said.

With more than 2,000 chemicals found in the water they soaked tire in, it took the team three years to narrow those thousands of chemicals to one.

“I think literally it was December 12, 2019, Zhenyu Tian was like, ‘hey I think I know what it is,” Kolodziej said.

A few months after the initial discovery, the team brought a sample of the chemical to Jen McIntyre over at Washington State University in Puyallup where it was put to the test.

“The fish would start to come to the surface of the water, they’d start swimming at the surface of the water, they would start to lose equilibrium and swim on their side and then upside down and eventually settle to the bottom of the tank and die,” said McIntyre who also explained how much testing was done to ensure accurate reporting and data.

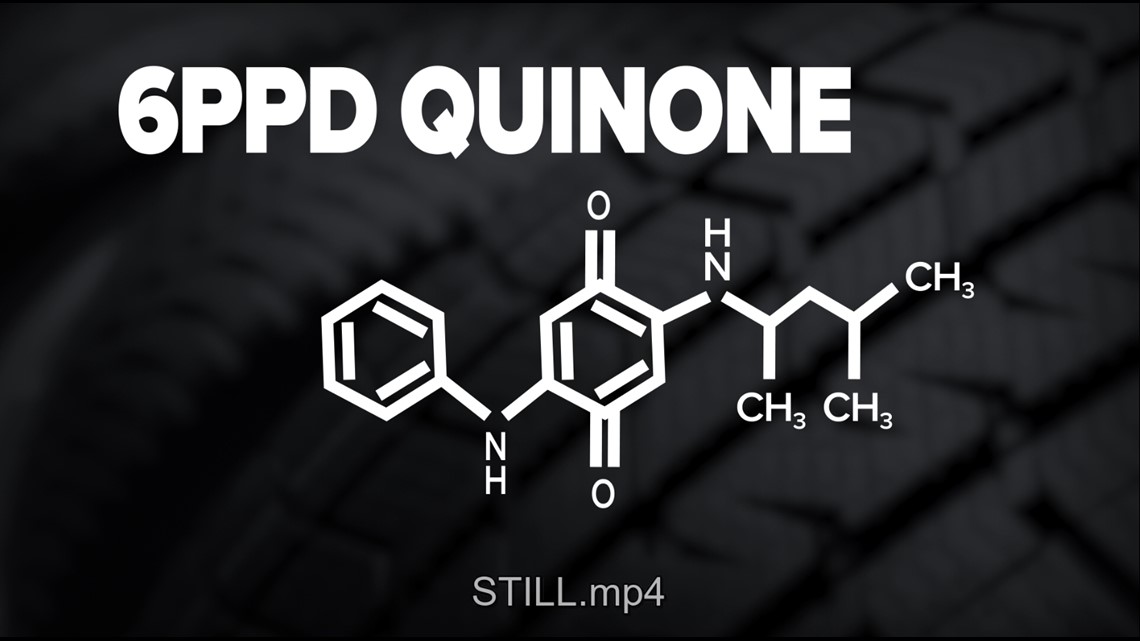

What they discovered was a toxin called 6PPD-quinone produced when the common tire preservative 6PPD mixes with oxygen. As tires age, the rubber starts to peel off leaving bits and pieces in their path.

When it rains anything that doesn’t soak into soil becomes stormwater pollution, eventually ending up in local waterways where every fall Coho salmon return to spawn.

THE SOLUTIONS

Kolodziej called the discovery a career-defining moment that brought “relief and excitement."

But the excitement faded with so much uncertainty surrounding possible solutions.

“Pollution data and where pollution comes from is highly controversial and highly augured over because the financial stakes over that are enormous,” Kolodziej said.

That’s where local advocates come in.

“They're literally soaking up this chemical that’s interfering with how their brains work and they're dying before they can get to that next part of the creek in order to lay their eggs,” said Sean Dixon, Executive Director at Puget Soundkeeper Alliance.

Puget Soundkeeper is a non-profit that’s been focused on clean water in the Puget Sound for nearly 40 years.

Dixon said we have to be walking and chewing gum at the same time given that 6PPD is in virtually every tire in America.

The U.S. Tire Manufacture Association addressed 6PPD in multiple ways on its web site saying in part the chemical adds to driver safety and that more research is being invested into the chemical and how it impacts Coho.

But even if the use of 6PPD was stopped, Dixon said it could be decades before it's completely eradicated.

Data from WSU shows that when stormwater pollution goes through green infrastructures, like a rain garden, it filters 6PPD-quinone out.

Puget Soundkeeper is now fighting for more Green Treatment Solutions near urban creeks pointing to permits that direct how cities and States handle new toxins found in stormwater.

“The permits today under the law today say if you got a problem, start figuring out how to solve it,” Dixon said.

Puget Soundkeeper sent intent-to-sue notices to five cities including Seattle, Burien, Mukilteo, SeaTac and Normandy Park for not complying with permits, but Dixon said the goal is to work with cities because he admitted solutions are expensive.

“I certainly don’t envy the task in front of these towns but what we can’t do is burry our head in the sand,” Dixon said.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

Advocates now hope for a stronger response from Washington state.

“This is being actively discussed between legislators and the Governor’s office and the Washington State Department of Ecology, but we are worried another year of conversations is going to go by,” Dixon said.

A petition was sent to the Washington State Department of Ecology asking for more action new Longfellow Creek in West Seattle which has seen pre-spawn mortality rates nearing 90%.

A response from the state was filed saying in part:

“The science is clearly making a case that 6PPD-quinone kills or harms aquatic species, and that municipal stormwater management is an important part of addressing this harm to aquatic life. At this time, we do not believe that a site-specific adaptive management effort is the most appropriate or a necessary response."

Jeff Killelea with the department of Ecology said they do have permit requirements for doing correction actions for site-specific hotspots, but he also says this problem (6PPD-quinone) is widespread and ubiquitous throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Killelea said the department of Ecology is figuring out how to best use funds received from the legislature to address multiple sites and researching ways to ensure solutions put in place today are effective in the long term.

“We certainly agree that actions are required to address and install treatment where it's needed," Killelea said. "We only disagree on the timing and the mechanisms for that treatment."

But Dixon said it’s time that poses the greatest risk.

“That’s something that our salmon can’t handle," Dixon said. "That’s something that our tribal communities don’t deserve. That’s something that our communities can’t wait for."