ASHFORD, Wash — Editor's note: The above video on Mount Rainier snowmelt following the June heat wave originally aired June 29, 2021.

If you're beginning to forget just how hot it got in the Pacific Northwest this summer, just take a look at a photo of Mount Rainier taken any time between early July and September.

The iconic, snow-covered mountain didn't look like itself following the June heat wave that shattered records in the region.

Mount Rainier's snowpack was well above the median in April. Snowpack then was in the top 10% of snowpacks on record, according to data from the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

That changed in June when multiple days of record-breaking temperatures caused the snow to melt at a dramatic pace. By July 14, what was one of the top snowpacks on record, was down to nothing.

Snowpack on Mount Rainier typically lingers until later in July and has even lasted until the end of August, according to data dating back to 1981.

Of course, that varies year to year, University of Washington Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Jessica Lundquist points out. In 2011, the mountain's snowpack reached into the top 10% and didn't fully melt until Aug. 27. Compare that to 2015, when Rainier received the least amount of snow on record, which was gone by May 30.

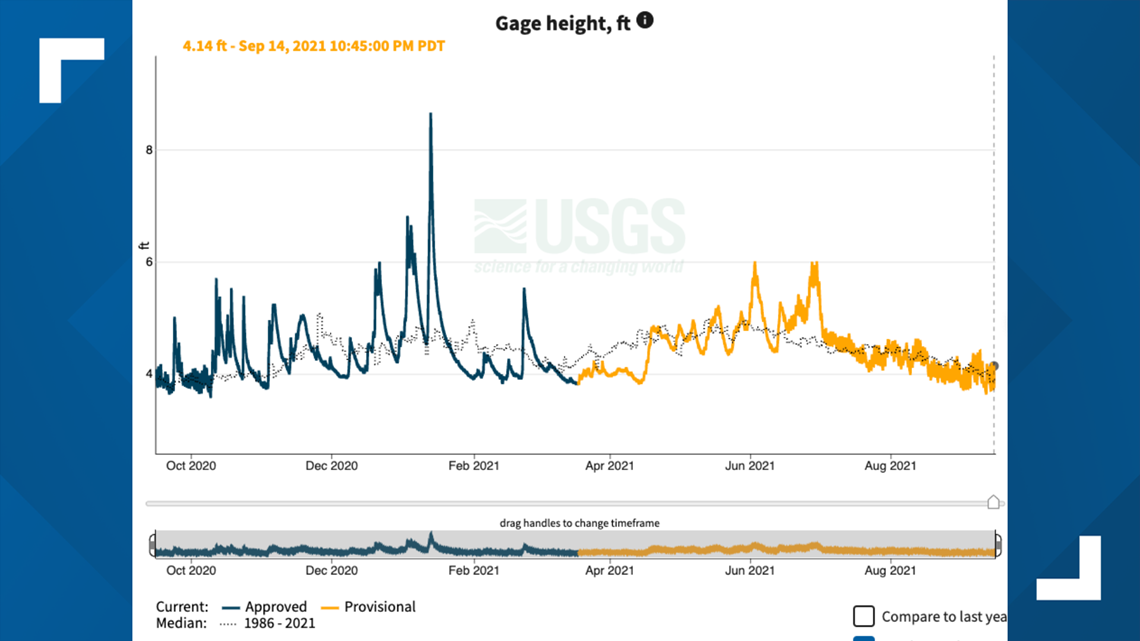

The water level on the Nisqually River, which is fed by the Nisqually Glacier on Rainier, spiked at the end of June and was higher than normal, according to data from the USGS. It was not as high as heavy rain in January, according to Lundquist.

Streamflow data for the Nisqually River from August shows evidence that snow, and possibly glacier melt, may have been strong. But Lundquist points out it’s not “obviously higher than the long-term median value” and more analysis is needed to tell how much streamflow is sustained by rain versus glacier melt.

There are 25 major glaciers on Mount Rainier. They support five major river systems. They are also “sensitive indicators” of climate change, the National Park Service says.

As an indicator of how the rapid snowmelt this year may have impacted the mountain's glaciers, in 2015, when snowfall was low and the snowpack was gone by May, glacial melt in the first half of summer was greater than early season melt in the previous 12 years, according to the National Park Service.

Because of the initially high snowpack, however, Mount Rainier's ecosystems were likely protected from much of the heat we experienced in the lowlands in June, according to Lundquist. The glaciers, too, would have been at least mostly spared.

That may be different for the remainder of the summer with no remaining snow.

Research indicates the rate of glacier recession will continue in the Pacific Northwest, impacting the region's more than 850 glaciers. A study in 2018 determined glacial melt will cause lower-elevation basis to suffer as streamflow is reduced. That means less water to feed river basins during drier seasons, with river volumes in late summer being reduced by up to 80%.

For glaciers to recover from summers such as this, they’ll need a more sustained snowpack like what we saw in 2011.