They never found David Johnston, the young scientist who put himself in harm’s way on the morning of May 18, 1980 when Mount St. Helens erupted.

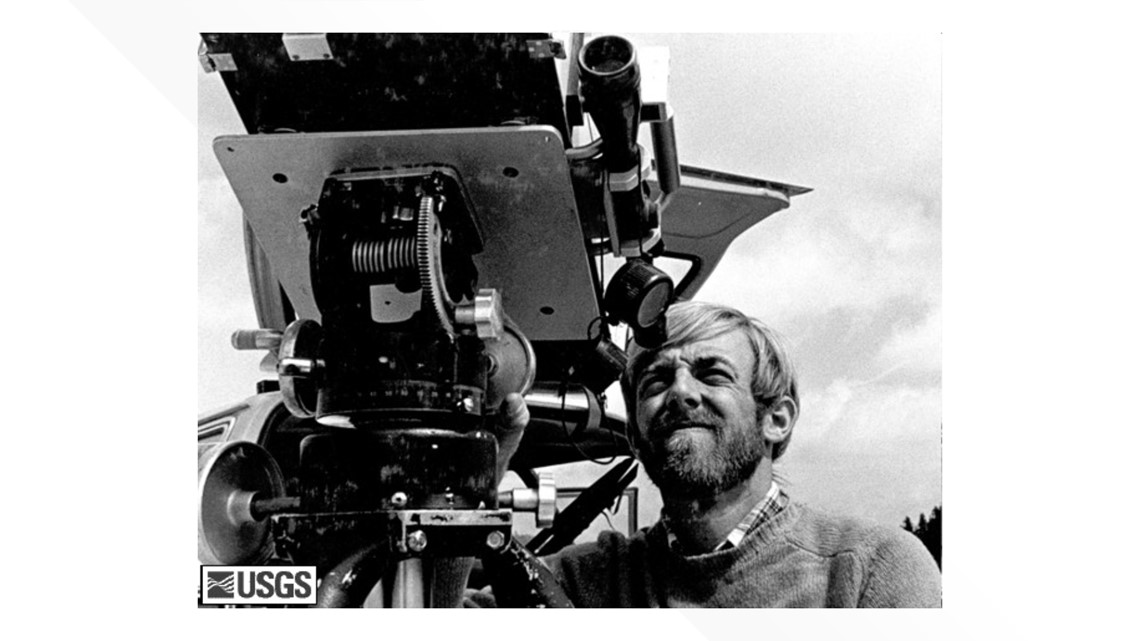

Specializing in volcanoes, Johnston had taken a shift to keep an eye on the bulging north side of Mount St. Helens over that weekend. He was working out of a camper, armed with a radio, binoculars and instruments.

What nobody knew was just when the mountain would erupt and how much warning anybody would get.

“David said, ‘We’re essentially next to a keg of dynamite,’” said Jeff Renner, then-KING 5 science reporter. Renner was also living on and off on the mountain covering months of buildup.

He often interviewed Johnston on St. Helens and had known Johnston since they first met on Mount Baker during unrest there two years earlier. But St. Helens was far more serious.

“He says the fuse is lit, but we don’t know how long the fuse is,” Renner said.

Johnston grew up in Illinois, which is not known for spectacular scenery much less geological unrest. He spent time studying volcanoes in Alaska before coming to the University of Washington, where he was a graduate student of now Professor Emeritus Steve Malone, who was also deeply involved in monitoring earthquakes at St. Helens in 1980.

“We didn’t know ultimately what would happen. We knew it was a very hazardous place,” said Malone.

He remembered flying over Johnston’s camping trailer in a helicopter days before the eruption. Malone was installing seismic stations to keep taps on the constant rumbling of tens of thousands of small earthquakes as magma moved deep under St. Helens.

“I was installing two stations on May 16 – one on Elk Rock to the west and another site near Timberline. And flying in the helicopter across there I could look over and see the camper that was up on Coldwater Ridge,” said Malone. “I was too far away to recognize who was there, but I could see someone; it probably was him.”

Two days later, Mount St. Helens erupted in a massive explosion. Malone said he thought of Johnston that morning.

“Very early on when I heard how big it was, that was one of my first thoughts not knowing,” Malone said. “And then probably late in the morning when word was coming in that the devastation area was huge, and it started to sink in.”

“David Johnston was literally blasted off the mountain ridge he was on, and his body was never found,” said Renner.

Renner, along with KING 5 Photographer Mark Anderson and Engineer Mike Carter could have suffered the same fate as they were camped, reporting on the mountain live not much farther away from the mountain than Johnston. They camped until the Thursday before when it seemed an eruption, if it even happened, was hardly imminent. Besides, it was Carter’s wedding anniversary that weekend, a compelling reason as any to take a break back in Seattle.

“Had you stayed, what would have happened?” I asked.

“I wouldn’t be talking to you today,” responded Renner.

The eruption had been unfolding slowly since the first small earthquakes were detected on March 16, 1980. There had been some steam explosions at the summit. The north face of the mountain was bulging out up to 6 feet every day. But there was no guarantee there would be a cataclysmic eruption. Besides, everyone thought there would be some warning, be it hours or days to get out of the way. There wasn’t.

“There just weren’t any changes in the data that said it was coming then versus anytime,” said Malone. “Even in retrospect you don’t see any changes.”

The sudden explosive eruption was best summed up by Johnston’s own words, said to sound more excited than fearful over the radio to colleagues based in Vancouver, Washington miles away: “Vancouver, Vancouver. This is it.”