SEATTLE — As the Pacific Northwest has seen a “massive increase” in people recreating in the backcountry, snow experts are urging people to be avalanche-aware this upcoming winter.

Thousands of avalanches are caused naturally – whether that’s from a big storm, rainfall on snow or wind blowing snow around – and most of these go unnoticed, according to Dallas Glass, deputy director of the Northwest Avalanche Center (NWAC). However, more than 90% of avalanches where someone is killed are caused by that person or someone in their group.

“The sort of idea that I'm like walking around in the forest and an avalanche like falls down off the mountainside on me, it can happen, but that's not really the avalanches we're concerned about,” Glass said. “We tend to trigger the avalanches that hurt us.”

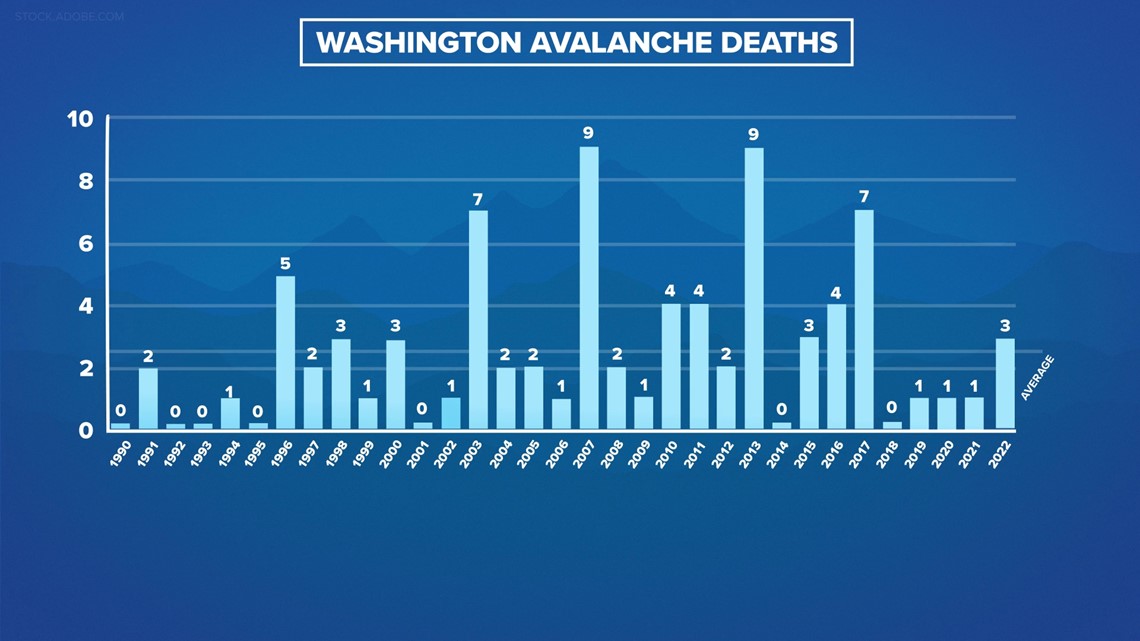

As backcountry users have increased, avalanche experts haven’t seen deaths tick up significantly, which Glass said is encouraging. In the last 30 years, Washington saw an average of 2.45 avalanche deaths per year, and in the last five years, it's dropped to 1.2 deaths.

Glass credited an increase in education and the availability of forecasts as primary drivers behind the flatlining of avalanche deaths.

This winter, forecasters have predicted a strong El Niño, which is a climate pattern that typically increases the chances for warmer and drier than normal conditions in Washington state.

“What I think was on our brain is anytime we're talking about warmer conditions, we have a lot of potential for big fluctuations, and a phrase you'll hear a lot in the avalanche world is big changes mean big problems,” Glass said.

Glass said there aren’t good long-term datasets to determine whether we expect more or fewer avalanches during El Niño or La Niña, which typically increases the chances for colder, wetter conditions. However, the region could see different types of avalanches depending on the conditions associated with each climate pattern.

For example, warmer conditions associated with El Niño years could lead to more wet avalanches, which can occur from rainfall, prolonged warm temperatures or sunshine on snow. However, El Niño is not a guarantee on the forecast and Glass stressed we could see quite cold weather during an El Niño as well, and avalanche conditions can change as quickly as the weather.

If you’re planning to get out into the backcountry this winter, NWAC urges people to be prepared by checking the avalanche forecast each time they go into avalanche terrain, carrying avalanche safety gear, including a beacon, probe and shovel, and getting proper training. Avalanche.org has free online resources, and NWAC has a calendar of free awareness classes on its website.

Though it’s snow-dependent, NWAC typically starts posting daily avalanche forecasts around Thanksgiving for 10 regions in Washington and northern Oregon, which include a snapshot of conditions and problem areas recreators are most likely to experience.

“My decisions matter,” Glass said. “So a little bit of education and some information can help me make good decisions and stay on the right side of that statistic.”