It has been a frantic week for fisheries managers in Washington state as they struggle to save a southern resident orca. The sick juvenile named J50 is not doing well.

"In very poor condition at present. She probably will not survive," said Ken Balcomb with the Center for Whale Research.

He's also the resident expert on the Southern Resident orcas. He began researching them for the federal government back in 1967 for what he thought would be a five-year study. Forty-two years later he's still at it, now trying to save the species.

"We've only got about four or five years of whale survival left, in terms of reproductive survival," he said.

Much of the focus the past 11 days has been on a mother, J35, pushing around her dead calf around the surface of the Salish Sea, mourning her loss. It's the latest in a series of those deaths over the past 10 years that have spurred many conversations about how to help. At the crux of the issue is a lack of food, according to Balcomb.

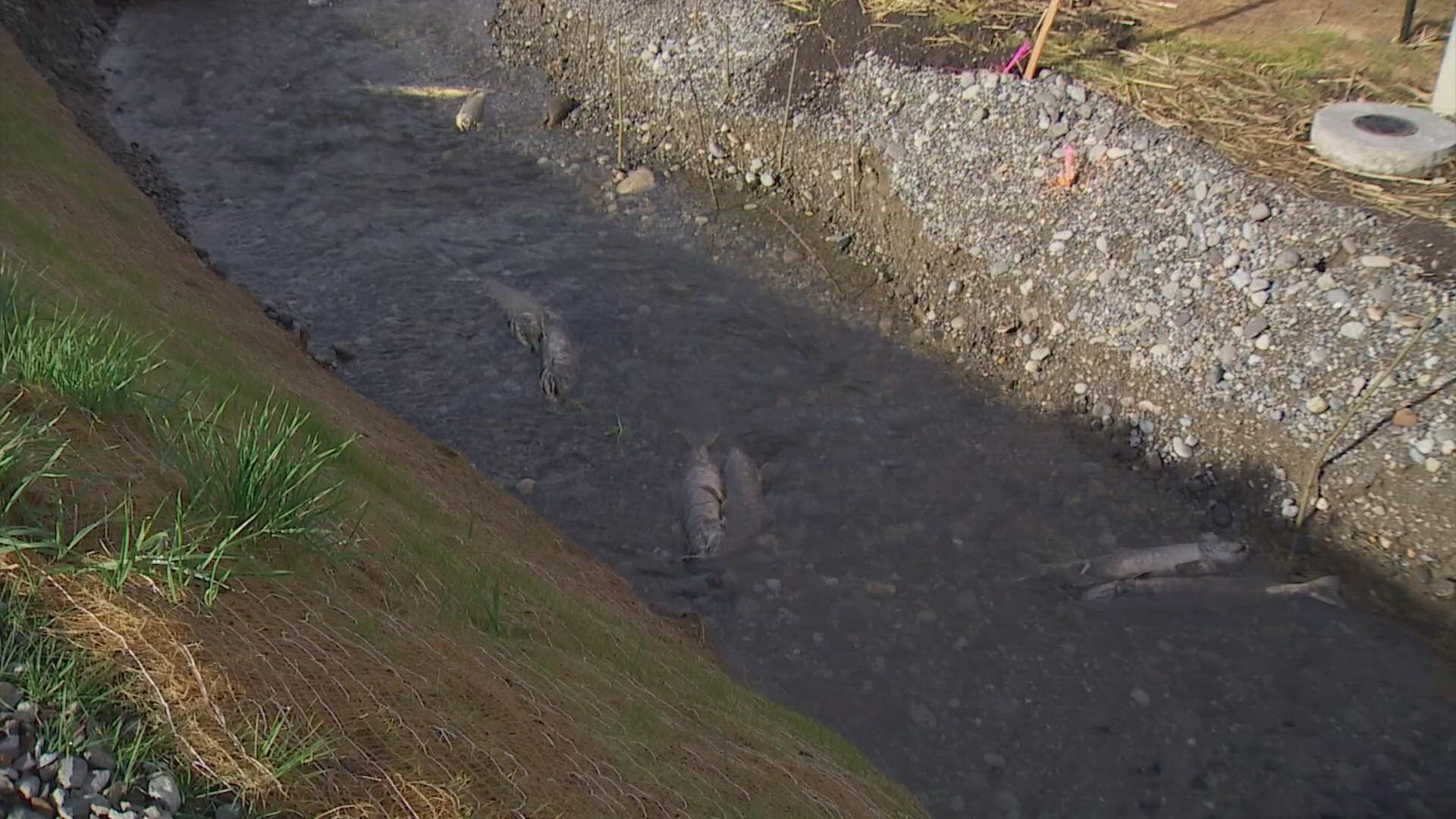

The Southern Resident orcas aren't genetically built to eat seals or sea lions like their transient cousins. Instead, they rely on fat-rich Chinook salmon that were once much more abundant. State, federal, and tribal leaders have been working together to bolster hatchery runs to supplement the dwindling native species, but so far it has been a failure.

Balcomb and others believe the biggest obstacle is four dams along the Snake River. Critics argue it could take decades to produce meaningful runs, but he says it could put millions more fish in the ocean within a couple years, possibly providing the orcas much needed food.

"We have to do something about getting more salmon available to them," said Balcomb. "And it's not going to be curtailment of human fisheries. It's going to have to be restoring the fish populations to at least some semblance of what they used to be."