Two deaths — no births. The annual census of Puget Sound’s resident orcas shows a continuing decline in their population, as the normally social killer whales focus their attention on finding enough food to survive.

The latest whale to go missing and presumed dead is 23-year-old Crewser, or L-92, according to Ken Balcomb, director of the Center for Whale Research. Crewser was last seen alive by CWR staff in November. That was before coastal observers reported that he appeared to be missing from L pod earlier this year. On June 11, Ken and his fellow researchers got a good look at both J and L pods in the San Juan Islands and concluded that L-92 was indeed gone. (Check out the CWR report on L-92.)

CWR report on L-92.)

Crewser was one of the so-called Dyes Inlet whales, a group of 19 orcas that spent a month in the waters between Bremerton and Silverdale in 1997. (I described that event for the Kitsap Sun in 2007.) Crewser was only 2 years old when he was with his mom, Rascal or L-60, during the Dyes Inlet visit.

Crewser’s 8-year-old brother, Raina or L-81, died soon after the whales left Dyes Inlet. Five years later, at age 30, his mother was found dead on Long Beach along the Washington Coast. Crewser remained with his grandmother, L-26 or Baba, until she died in 2013.

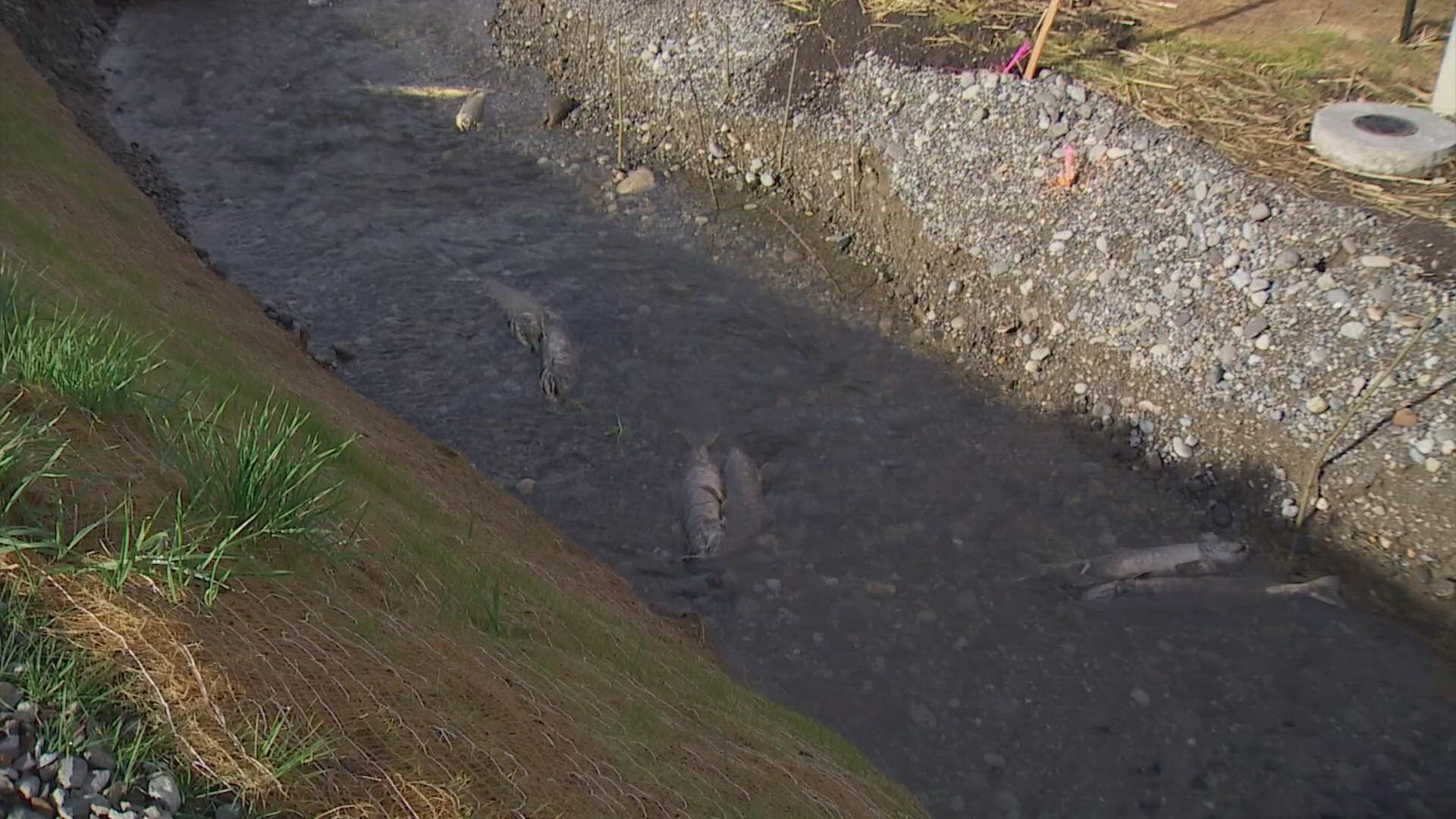

Too many deaths and too few births led to the listing of Southern Resident killer whales as an endangered species in 2005. The bodies of dead orcas are generally not recovered, so the cause of death for most orcas remains unknown. But the greatest concerns for the whales relate to accumulations of toxic chemicals in their bodies and the ongoing difficulty of finding enough food, since chinook salmon — their primary prey — is a threatened species.

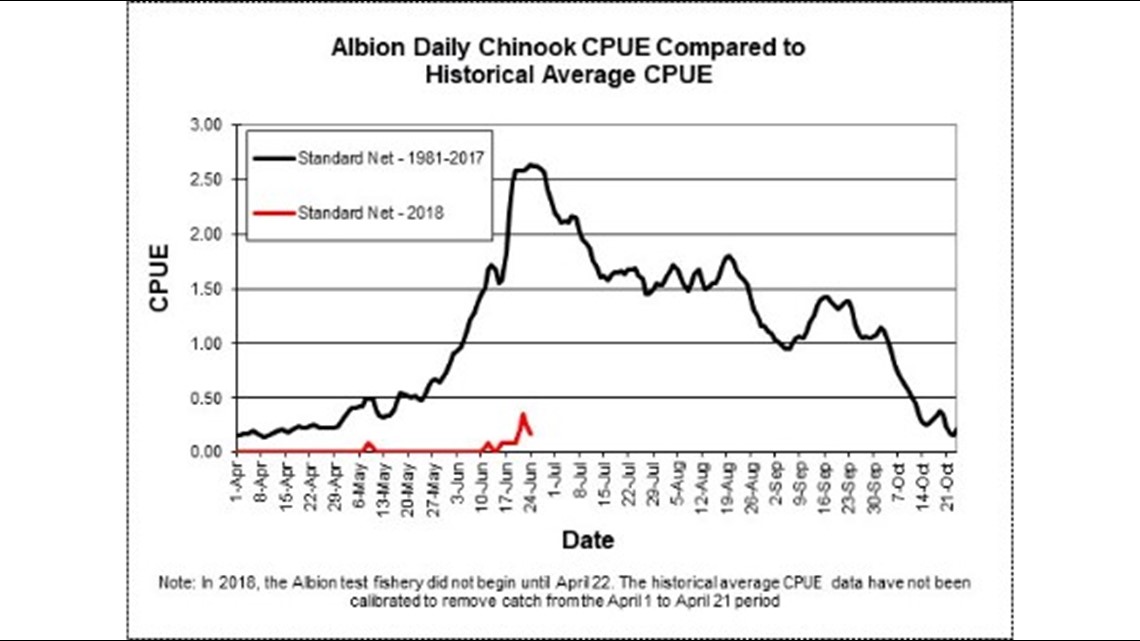

The whales are clearly lacking food in the spring, when they depend primarily on spring and summer chinook returning to the Fraser River in Canada as well as other streams, Ken tells me. Take a look at the Albion test fishery, he said.

The Albion test fishery involves two nets designed to catch chinook salmon at the mouth of the Fraser River near Fort Langley, B.C. It has been operated in the same place since 1981. The graph on this page shows the average harvest compared to this year’s harvest. Although the Albion test fishery does not tell the entire story, it tells us something about how the chinook runs have declined dramatically through the years.

Low chinook returns have led to a disruption in the social structure of the whales and changes in their foraging patterns.

“The whales are very spread out,” Ken said, adding that years ago he would see them foraging together in close groups, and every whale would get a share of the fish. Now they seem to be searching more instead of just sharing.

The Center for Whale Research has a new aerial drone, approved for orca research. This week, Ken observed from the air as a 23-year-old female, J-31 named Tsuchi, seemed to be “looking” for fish from the surface.

“She was putting her head down and scanning deep,” Ken said. “Then with swoops of her tail, she dove deep as other whales swam toward her.”

No doubt she was using her echolocation (similar to sonar) to get a picture of the conditions underwater. She must have seen some fish. It would have been nice to have a hydrophone in operation to learn how she called the other whales to her location, Ken said.

The lack of a reliable food supply in the San Juan Islands has made the whales’ travels more unpredictable than ever. None of them showed up this year during the entire month of May, something that has never happened before. In June, the whales have been around more, but their behavior suggests that they are not having great success in finding salmon.

The population of Southern Resident killer whales has been on a steep downward course since 2012. (See CWR population graph.)Now, the total number of animals – 75 for all three pods — is close to the lowest population seen at any time over the 42-year history of the orca census, which began after the roundup of dozens of whales for marine parks. The census has been maintained each year by the Center for Whale Research.

The census is a count of the Southern Residents on July 1 each year. That’s when the number of new calves are tallied, and missing whales are put on the death list. Ken says he has seen all the Southern Residents this year except those already reported missing plus five L-pod whales that haven’t shown up. They are likely to be in waters off the coast, he said. Since the July 1 census count is not turned over to the federal government until Oct. 1, there is still time to make sure that none of those five unseen orcas has died.

In addition to Crewser, a 2-year-old male calf named Sonic (J-52) went missing last September. He was the first known offspring of Alki, or J-36, who is 19 years old. The likely cause of Sonic’s death is starvation, as he was showing signs of “peanut head” caused by the loss of blubber. (See the report from CWR at the time.)

Ken told me that he has concerns about a young female whale named Scarlet (J-50), who has often been trailing the rest of her pod and is showing early signs of peanut head. She’s not on a death watch, Ken said, but she is not in a robust condition either. Scarlet’s mother is believed to be Slick, J-16, who is also the grandmother of the deceased Crewser.

Early in the lives of these calves, there was some confusion about the parentage of Sonic and Scarlett. Check out Water Ways, March 31, 2015. They were both part of a yearlong “baby boom” that resulted in nine new orcas, three of which have since died.

When the annual census comes around next year, I truly hope I can report more births and fewer deaths.