SEATTLE —

The "Beast Quake" of 2011 is a moment that will go down in history, when Marshawn Lynch scored a touchdown and the crowd went wild, causing record-breaking seismic activity.

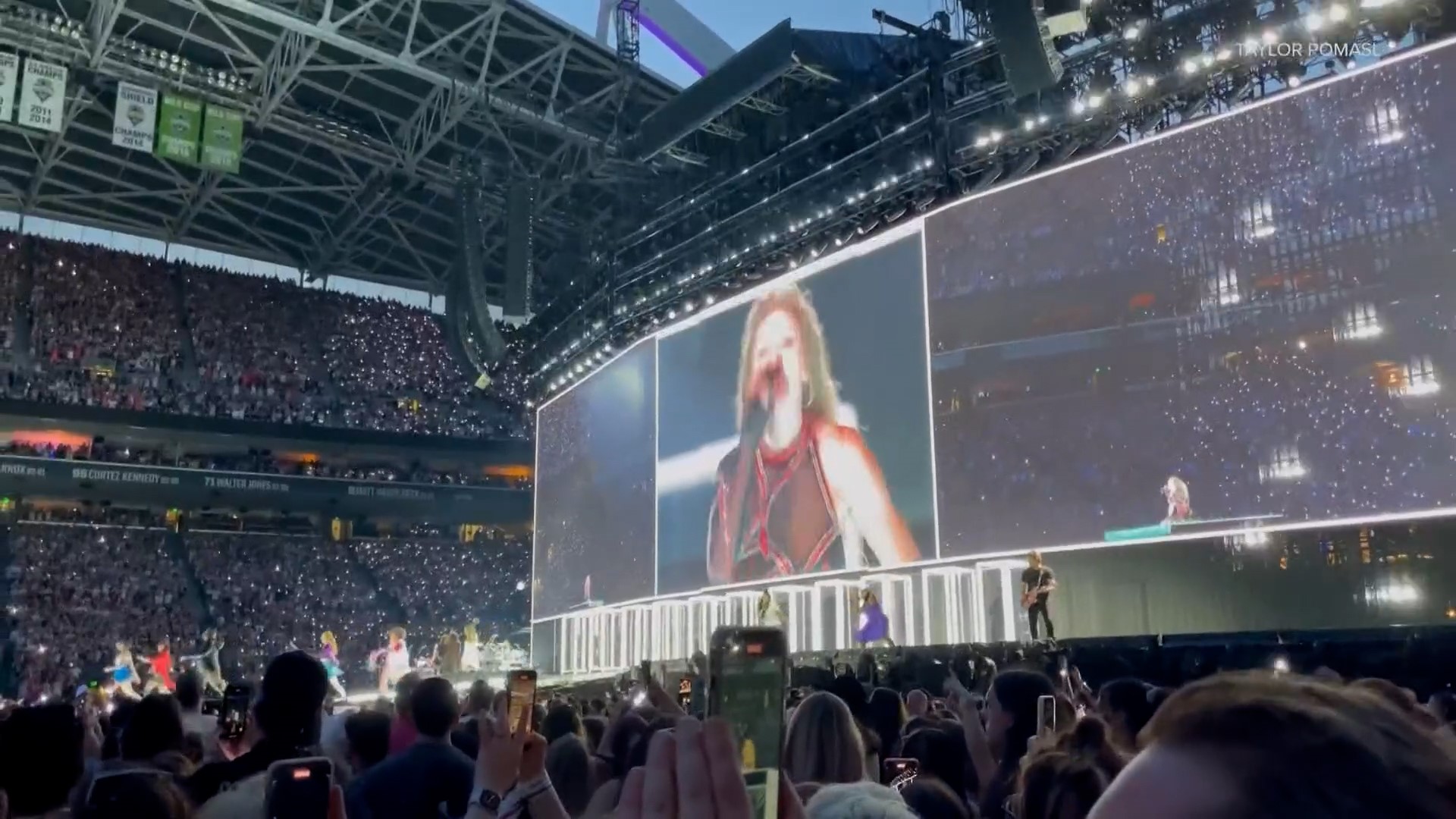

Now, Taylor Swift fans have topped that seismic activity after screaming and dancing for two straight nights at Lumen Field in Seattle.

Western Washington University geology professor Jackie Caplan-Auerbach said she’s part of a Pacific Northwest earthquake Facebook group and saw someone ask how the seismic activity from the two events compared.

“Somebody posted and said 'Well, did the Taylor Swift concert make a Beast Quake?' And I was like 'Oh I am on that, that’s fun',” she said.

She got to work, pulling the data from the two nights of concerts.

“So I grabbed 10 hours of data from when doors opened to well after I thought the audience had gone home and I just plotted them out to see how did the ground shake,” she said.

The numbers show that not only did the ground shake, but it shook in a steady pattern matching a beat in an almost identical pattern each night. She noticed one difference between the two shows.

“I actually kind of did math and saw to my data it looks like it was delayed 26 minutes and somebody commented and said oh yes it was delayed about half an hour,” she said, showing that the data perfectly matched the concerts.

She said comparing the Seahawks fans and Swifties roar is a bit tricky because Taylor Swift’s crowd was a bit larger, played directly on the field and everyone was moving in sync, but still, the winner of seismic activity is clear.

“I want to put that caveat out there because I don’t want a snickering match between Seahawks fans and Swifties but I will say Swifties have it in the bag. This was much bigger than the Beast Quake in terms of the raw amplitude of shaking and it went on for a whole lot longer, of course, the Beast Quake was a moment in time, but thus far the Swifties really have Seahawks fans beat,” she said.

She said it’s tricky to compare the magnitude difference of the two, but she did the math and says one "Swift Quake" is about twice as big as a Beast Quake, which is a magnitude difference of a 0.3 quake, but emphasizes that the Beast Quake was only a few seconds compared to an hours-long concert.

Jackie added that she noticed a low hum that’s not possible to hear from the human ear and wants to investigate this further, so she’s now trying to collect information regarding what time each specific song started, hoping to get it figured out by the second. If she gets that data, she’ll be able to test her hypothesis that the low hum is from dancing fans.

She's currently working with some teens in her neighborhood who went to the concerts to collect data in the form of videos from the concert. If any Swifties are able to help her, she asks they reach out via email at caplanj@wwu.edu.

Jackie also points out that this experiment is a fun way to get people excited about science in an easy-to-digest, fun way.