SEATTLE — Seattle's new State Route 99 tunnel is designed to hold up against most major earthquake threats the Pacific Northwest faces – including "The Big One."

The new Highway 99 tunnel running under downtown Seattle is designed to last a century. Over the next 100 years, there is little question it will have to withstand at least two earthquakes, like the most recent 2001 Nisqually earthquake, which was a deep magnitude 6.8 that damaged the Alaskan Way Viaduct the tunnel is replacing.

But a deep quake like Nisqually isn’t the only threat, so what are the odds?

Earthquake scientists forecast an 84 percent probability of another Nisqually-type of quake in the magnitude six or greater range happening during the next 50 years. A Cascadia Subduction Zone event off the coast, which is expected to generate a magnitude 9.0 quake with the worst shaking the further west you go, rates about a 15 percent chance in a half century. So does a potentially much closer and more damaging quake from a crustal fault, like the Seattle Fault that runs just south of downtown.

The Seattle Fault expected to be a magnitude 7. While that doesn’t sound that much worse than a Nisqually-type of quake, Nisqually was centered 30 miles below the surface, where a quake from the Seattle or South Whidbey Island faults would be at or near the surface and considered much more potentially devastating. Scientists don’t know how often the Seattle Fault goes off; the last one was around 1,100 years ago. Then there’s the South Whidbey Island Fault and others, perhaps faults as of yet undiscovered.

“It includes all of that,” said Jim Struthers, the chief engineering geologist for the Washington State Department of Transportation, on what the tunnel is designed to withstand.

The main reason the tunnel was built was to eliminate the earthquake vulnerability of the viaduct. One of the key reasons why the tunnel would fare better is because it’s buried in the ground and would move with the earthquake as the ground moves, where the viaduct would sway like a building snapping at its joints. It was at the joints where it began to come apart as the ground below the viaduct began to move slowly in the weeks after the Nisqually earthquake.

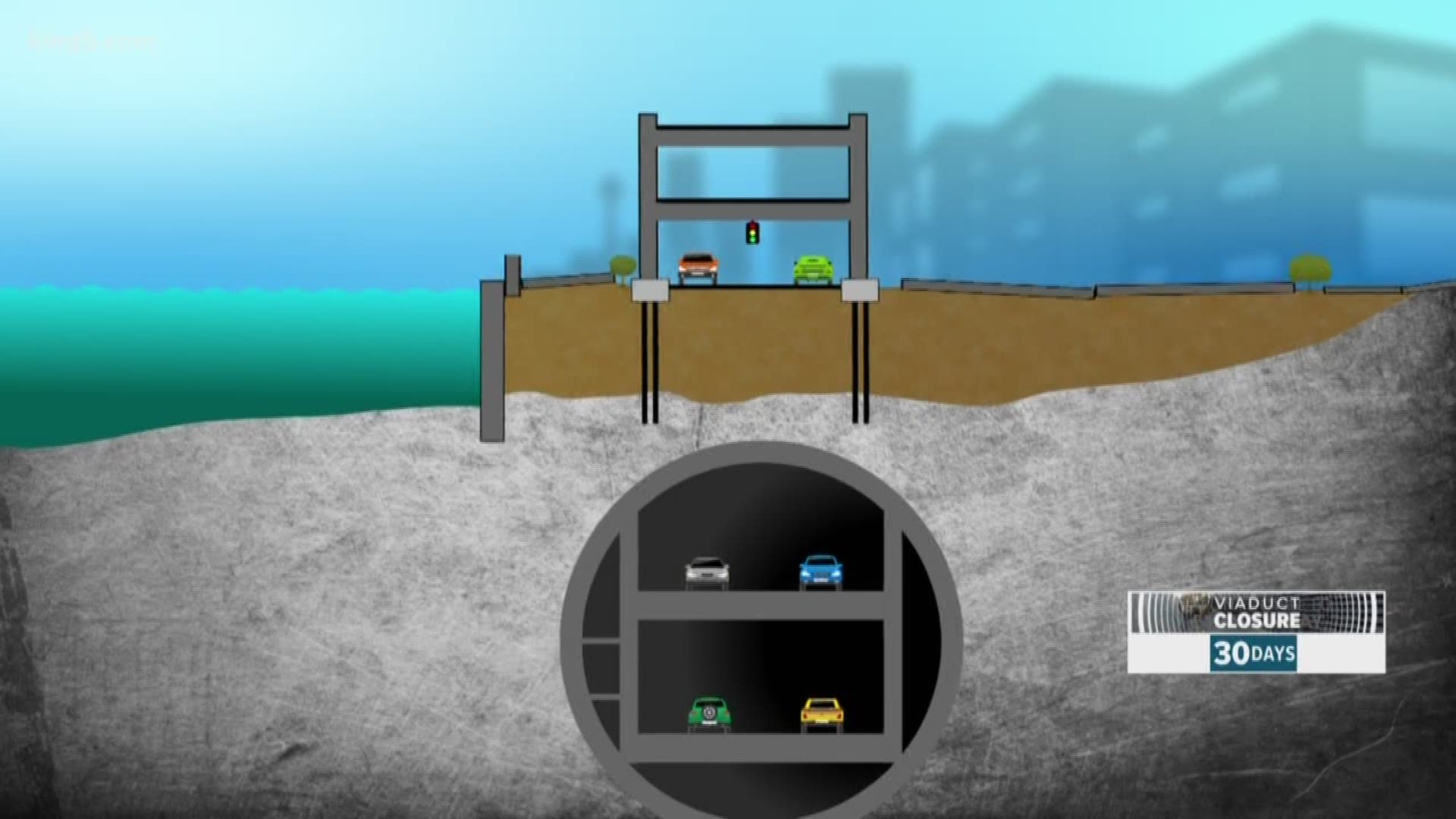

The tunnel is flexible; its outer shell is built from bolted-together rings. Each ring is made from several segments, all with a rubber gasket in between them. The rings are nearly 58 feet in diameter with the double-deck roadway inside.

“When you look at an individual segment, it’s a fairly massive piece of concrete,” said Struthers. “At the scale of the diameter of the tunnel, there is quite a bit of flex in there. And so the approach that was taken for the tunnel was to actually simulate real earthquake ground motions coming into that structure at different nodes and to actually check its flexibility during the type of earthquake you would expect.”

There are also two types of tunnels. When you drive through it, you won’t really see much of the round outer structure except on the top or northbound deck. There is the bored tunnel mined out by the tunneling machine named Bertha. Then there are the portals – so-called cut-and-cover tunnels. Between them is another rubber device, which isolates the shock to one from the others. The differences in earthquake wave frequencies would vary depending on the type of earthquake and affect the structures differently.

Struthers won’t go as far as calling the tunnel “earthquake-proof.”Some level of damage is not out of the question. But it is considered state-of-the-art – for now.

Join KING 5's Seattle Tunnel Traffic Facebook group to stay up-to-date on the latest Seattle tunnel and Viaduct news and get tips to battle traffic during the three-week Viaduct closure in January.