Thursday, March 11 marks 10 years since Japan’s Tohoku earthquake in 2011.

The magnitude 9.1 temblor and the tsunami that followed killed 16,000 people, caused the Fukushima nuclear power plant to meltdown and sent huge amounts of debris to Washington’s beaches. The disaster was also a reminder of the kind of quake and tsunami that will happen on our own coastline, as more communities prepare for that day.

“I can’t think of a single other event that has motivated state, federal and local partners to move forward with tsunami evacuation and mitigation planning,” says Tim Cook, who leads hazard mitigation for Washington’s Emergency Management Division.

In some communities, work was already underway. The Quileute Tribe in La Push has conducted emergency evacuation drills for decades to get people to higher ground from the lower village which is close to sea level.

The tribe acquired land and in 2017 began clearing a section to start the process of moving that lower village to higher ground.

That starts with the tribal school, and now construction of a new 60,000 square foot building 250 feet above sea level is well underway with an opening planned for the fall of 2022.

Ocosta Elementary School south of Westport erected North America's first community vertical evacuation structure as part of new school construction opening in 2017. The residents taxed themselves with a school bond to build it.

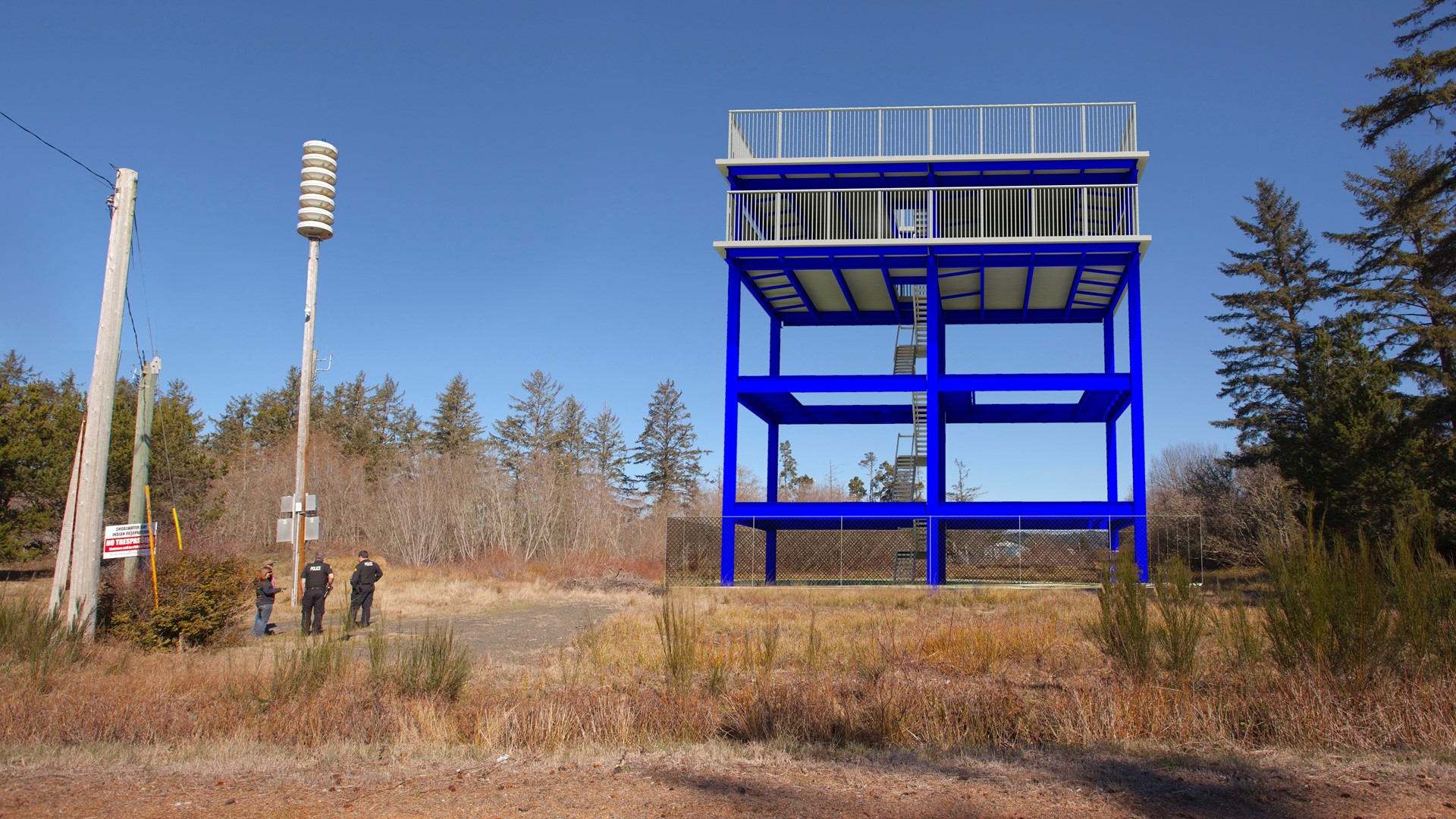

Further south the Shoalwater Bay Tribe expects it will begin construction of a stand-alone vertical evacuation tower by late spring, which will also welcome residents of nearby Tokeland.

Elsewhere, Cook says Ocean Shores has lined up funding for the first of what is likely to be several towers, and Westport itself has started its planning.

“If all goes as planned, their target is the summer of 2022 for construction,” says Tim Cook in regards to Ocean Shores. "Westport secured Federal and state grants to help with preliminary design."

Building the structures can cost millions of dollars, and it’s not just construction.

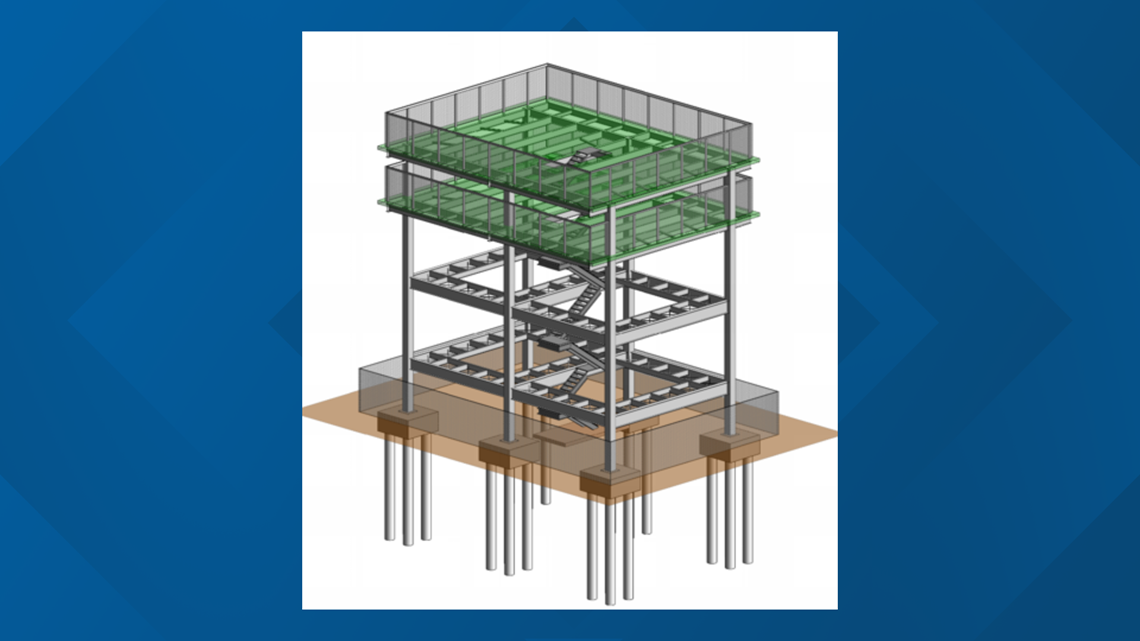

The structures need tsunami modeling, which shows where the waves go based on the severity of the earthquake.

Depending on the soil the tower sits on, much of the construction work goes into the foundation as the tower will have to survive a massive quake even before the waves come in, which could happen in as little as 15 to 20 minutes.

Designs can range from dedicated towers to dual-use facilities with some ideas include raised sections of reinforced Earth, which could be used as a park or ball fields, but located high enough to avoid being topped by tsunami waves.

Washington’s Emergency Management Division plans to release a revised guide to building and financing evacuation structures in April.