KING COUNTY, Wash. — As western Washington experiences its hottest day of the year Monday, King County officials announced its first-ever action plan to reduce the impact of future heat waves.

The new "Extreme Heat Mitigation" plan is part of King County's Strategic Climate Action plan.

County health officials said the plan's goal is to help people adapt to "inevitable heat events," give them better resources to mitigate the effects of heat and find community solutions to decrease greenhouse gas emissions.

King County applied for a $125,000 grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to help fund the heat mitigation plan, but it has not been approved at this time.

Officials are already in the process of several action steps designed to help tackle heat waves, including:

- Adding metro bus shelters in the hottest temperature areas

- Planting trees for its 3 Million Trees initiative

- Volunteers helping people have access to emergency heat information

- Replacing gas, oil and electric furnaces/air conditioners with energy-efficient heat pumps for low-income homes

- Offering low-cost private loans to commercial and multi-family residences to make energy-efficient upgrades

In the heat mitigation plan, the county outlined long-term steps it hopes to incorporate in its fight against rising temperatures, including:

- Changing building code requirements to better protect against rising temperatures

- Incentivizing landlords to upgrade units with better heat protection

- Upgrading rental properties

- Depaving more areas and adding more "green spaces"

- Adding water features to more neighborhoods, giving people places to cool off

- Preserving about 65,000 acres of open space in King County before it is turned into buildings or commercial developments

WATCH: King County officials discuss the "Heat Mitigation Plan"

On the hottest day so far this year, many tried to escape the urban heat island.

"You always think of water when you want to cool off,” said Raymond and Diane Lewis who came to Mercer island to bird watch.

The couple remembers what a Seattle summer used to be when they were kids,

“It wasn’t near as bad as it is now,” Raymond Lewis said.

Last year's record-breaking heat wave saw the highest ever recorded temperatures in Seattle and multiple days in a row of triple-digit highs across the Puget Sound region. Temperatures reached as high as 118 degrees in Maple Valley and 116 degrees in Issaquah.

The Washington Department of Health (DOH) said 91 people likely died because of the historic heat wave across the Pacific Northwest from late June to early July. The majority of these deaths occurred in King and Pierce counties.

A 2021 study suggested Washington state’s historic heat wave would have been nearly impossible without the effects of climate change.

“We experienced the single-most deadly climate event in our history and we know that these events are threatening us now," said Jeff Duchin, King County Health Officer. "They are getting more frequent, expected to be longer in duration and they are going to more intense. We really need to do what we can to minimize the risk from these heat waves becoming more catastrophic in the future.”

To compare, there were just seven heat-related deaths in all of Washington state from mid-June to the end of August in 2020. From 2015 to 2020, there were a total of 39 heat-related deaths in the warmer months of May through September.

Gabriel Debay, Shoreline Fire Department medical services officer, said there were often between 10 and 15 ambulances with heat stroke patients waiting outside of Harborview Medical Center at the peak of the 2021 heat wave.

A five-minute delay in these instances could be the difference between life and death, Debay said.

“I never thought I’d see so much heat stroke in a short period of time," Debay said.

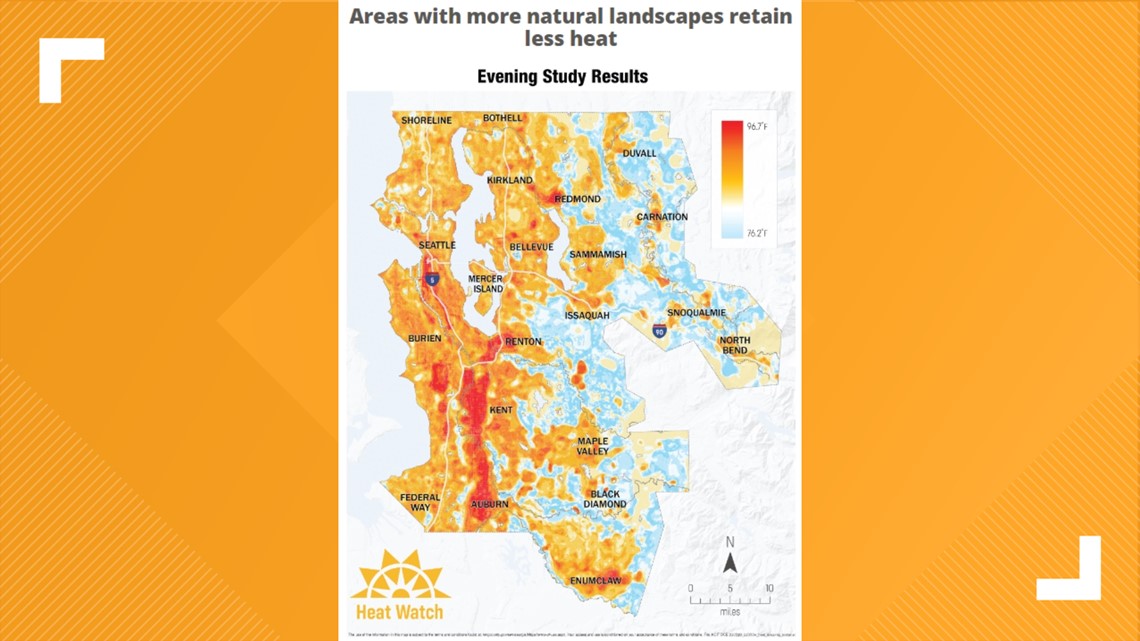

A heat mapping project in 2020 by King County and the City of Seattle measured how heat waves affect different communities. The project found that at the same time and place in the county, temperatures in the Ballard neighborhood reached 85 degrees, while Kent reported 96 degrees.

The study found warmer areas of King County typically have more pavement and hard surfaces that retain heat and amplify temperatures during a heat wave. The cooler areas have more tree canopy, parks and natural landscapes insulting the neighborhood from higher temperatures, according to the project.

King County Climate Preparedness Program Manager Lara Binder said there can be as much as a 23-degree difference in temperatures across King County at the same point of the day, based on differences in geography, land use and tree canopy.

Researchers at the University of Washington found an increase in emergency medical service calls, hospitalizations and mortality in King County during hotter temperatures.

The heat map project said heat-related health risks in King County are magnified by inequalities in housing, healthcare access and health outcomes. The people most at risk of heat stroke are older adults, children, pregnant women, people who work outdoors, unhoused people and those with chronic medical conditions, according to the study.

Many of the areas affected by higher temperatures happen to be the same areas disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and other health inequities. ]

Binder said she wants officials to focus on adapting local environments to make them better protected against heat.

“While extreme heat affects everybody, not everyone is affected equally," Binder said.

In July 2021, dozens of people died in the Pacific Northwest during the historic heat wave. On June 28, temperatures in Seattle reached 108 degrees.

“Last summer put an exclamation point on what we’ve known for awhile: We need to deal with what we know is coming and we need to prevent what’s preventable," Duchin said.

As temperatures continue warming up around the region, heat has proven to be the biggest weather related-killer in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The CDC said around 618 people are killed by extreme heat annually. The number of heat-related deaths was even higher for a 15-year span from 2004-2018, according to a CDC morbidity and mortality report. During that time, there was an average of 702 heat-related deaths in the U.S. every year.

Floods, the second-deadliest weather-related hazard in the U.S., account for about 98 deaths per year.