SEATTLE — The northern lights could dance over the Pacific Northwest this week as a geomagnetic storm approaches Earth.

This storm isn’t on the same scale as the historic May 11 aurora, but there are similarities between the two events.

How the May 11 storm formed

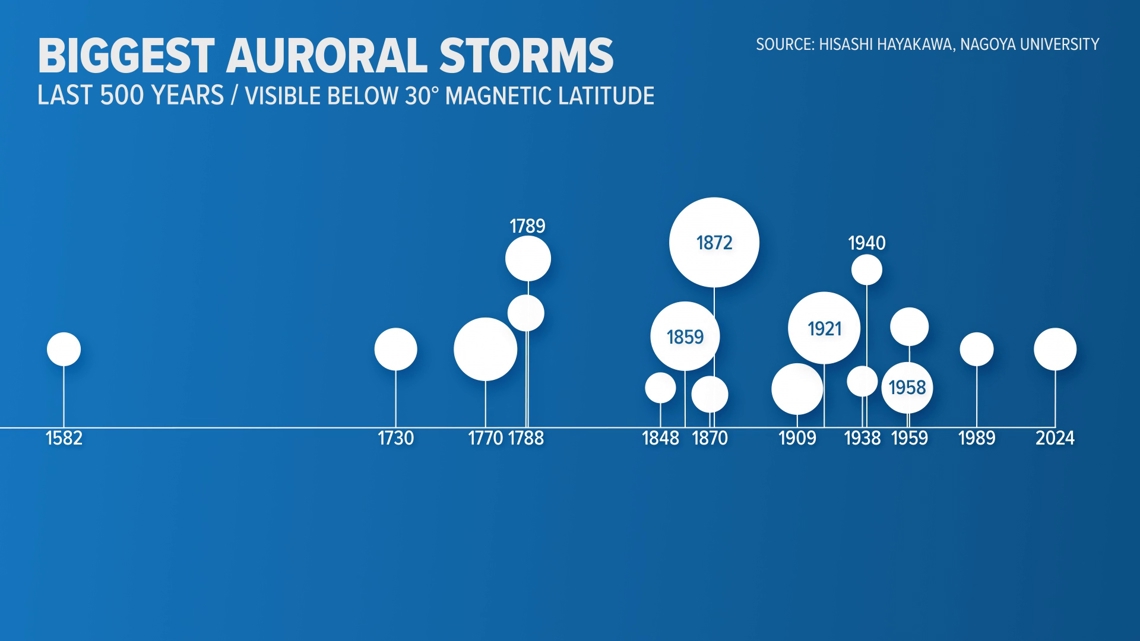

It’s estimated the May 11 auroras were among the top 20 geomagnetic storms in the past 500 years, according to an analysis from Nagoya University researcher Hisashi Hayakawa.

But why was the May 11 event so powerful? It all starts with the sun, which is a star made up of super-hot electrified gases called plasma that are bound together with strong magnetic fields. Unlike the Earth’s relatively steady magnetic field, the sun is a twisting and turning mix of plasma and magnetic fields.

The magnetic fields and the plasma perform a complex dance that we see at the surface of the sun, looping and stretching – looking a little like a pot of fast boiling water. The most active areas are usually associated with groups of dark sunspots.

The magnetic lines can stretch out too far and break and snap like a rubber band, sometimes launching huge “bubbles” of plasma and magnetic fields out into space. This is what solar scientists call a coronal mass ejection (CME)

The “snap” is often accompanied by brilliant flashes of high energy light called solar flares.

And if the CMEs are launched in the right direction from the sun, they can hit the Earth’s magnetic field and cause a geomagnetic storm.

The amount of magnetic turmoil on the sun follows an 11-year cycle.

During what scientists call solar minimum, there are few sunspots observed and the sun’s magnetic field is quiet with very little twisting and turning. But during solar maximum, there can be frequent and large sunspots and the sun’s magnetic field can churn constantly, shooting out frequent and large CMEs.

In 2024, the sun is approaching the 11-year maximum, and solar activity is expected to be heightened for months.

Now we have all of the elements for the monster geomagnetic storm that caused the May 11 auroras.

First, we are approaching a solar maximum right now and the sun has been very active with frequent CMEs, although most are not aimed at the Earth.

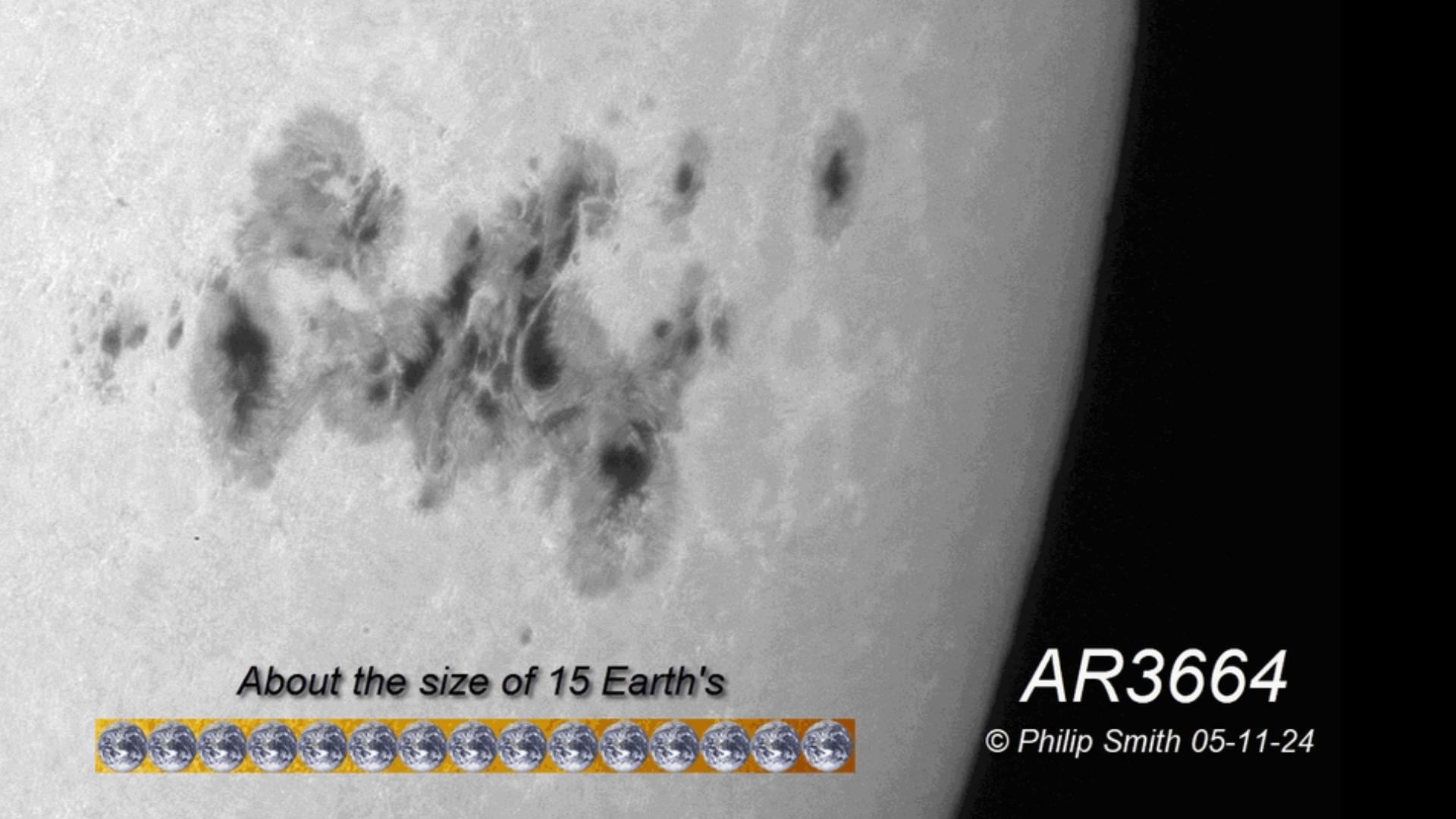

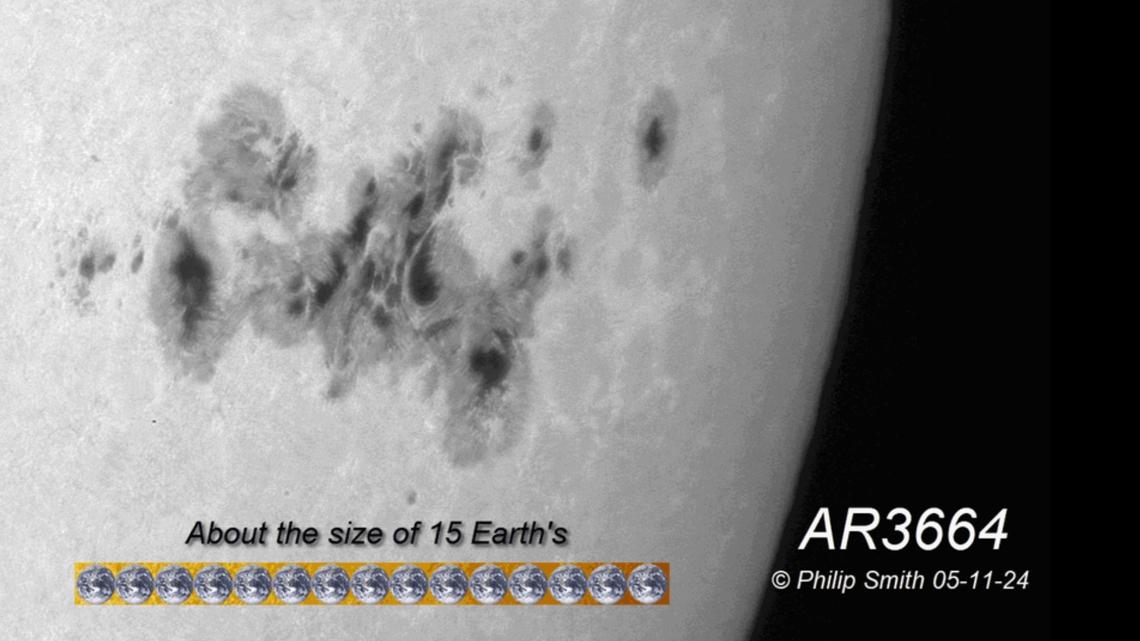

During the week before May 11, a giant sunspot group wider than a dozen Earths formed and began producing solar flares and CMEs.

Beginning May 7, the giant sunspot group spit out four CMEs in quick succession just as it was in the right place on the face of the sun to send those CMEs in Earth’s direction.

CMEs can be launched at different speeds ranging from 60,000 miles per hour to almost 6 million miles per hour. In this case, the fourth CME was the fastest and quickly overtook the took. This combined all of their plasma and magnetic fields into a giant CME or what is called a cannibal CME.

This is what blasted the Earth’s magnetic field on May 11 for the extreme geomagnetic storm and the incredible display of northern lights.

At least three more, slower CMEs blasted out of the sun that week and they maintained the auroras at a much lower level for another two to three days but not like May 11.

What’s happening this week

The source of the July 30-Aug. 1 geomagnetic storms is also from a succession of CMEs being ejected from the sun.

They are coming from a new sunspot group that’s different from the source of the May 11 event.

In the last few days, between six and seven CMEs were ejected from the sun. Although they are much smaller than the CMEs that caused the May 11 event, they combined into a cannibal CME, which also happened several months ago.

The first CME moved slower than the rest, allowing the others to overtake it.