This winter has produced nearly 50 notable landslides in the state, according to the Washington Geological Survey.

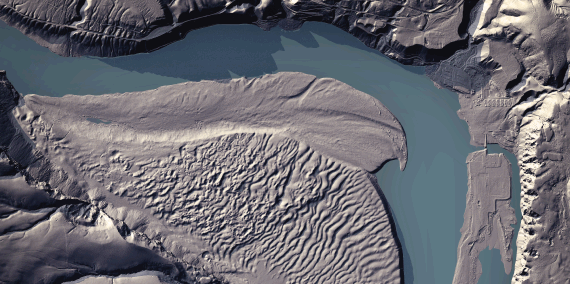

A Lidar Portal on the Washington Department of Natural Resources website maps landslides, elevations, and provides valuable information to geologists.

“When you have a wetter-than-average winter, there’s always going to be a red flag in my mind,” said Alison Duvall, a geomorphologist at the University of Washington. She studies the Earth’s surface, and is an expert on how that surface changes.

Duvall said over the course of a wet winter, slides can grow deeper and bigger. Even in drier weather, soil stays saturated.

“That means that deeper landslides can be affected by that collection of water, well after the rain has stopped,” Duvall said. “We’re not out of the woods once the rain has stopped, especially after a really wet winter.”

Blame it on “pore pressure.” When you dump a glass of water onto the ground and see it absorbed, it is being sucked into a sponge of sorts, taking up space between the grains of soil, sand, and other particles that make up the ground we walk on. During heavy, extended rains, those spaces or “pores” fill up fully, and building hydraulic pressure can drive the particles apart. Pressure inside an already steep slope increases risk of slope failure. And the water already there won’t be evaporating any time soon.

Even when rains taper off, the soft soil is less able to hold the roots of trees, and now strong winds are in the forecast this weekend.

So while the skies may dry out for Puget Sound, the landslide risk could continue well into spring.

“It is a strong concern for me, it’s always in the back of my mind," Duvall said.