While all runs of salmon on the Skagit River experienced declines, Seattle City Light left 20-year-old glowing messages on its website – touting the utility’s stewardship that led to “strong” and “landmark” returns of salmon.

The public messages are at issue as Seattle’s hydropower dams on the Skagit River are undergoing relicensing by the federal government. The relicensing process has created heated controversy as Seattle City Light representatives pushed back on tribal, state and federal scientists who are demanding the city to do more under a new license to mitigate the utility’s impact on salmon and other species, including orcas.

Seattle City Light revamped its entire website at the end of January. But prior to that, anyone looking up information on the utility’s operation on the Skagit River would find rave reviews from City Light, which dubs itself “the nation’s greenest utility.”

Web pages dedicated to the Skagit Project reported to ratepayers that the city’s way of doing business “means inexpensive hydroelectricity for you and a healthy salmon population for the Skagit.”

But current data from the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) shows salmon populations on the Skagit are not healthy.

Chinook salmon are listed on the endangered species list, as are Skagit steelhead, bull trout and orcas that depend on Chinook from the Skagit as their most important food source.

“[To say they’re healthy] is not the real story. The salmon are in trouble,” said Ed Eleazer, WDFW regional fish manager. “If things were rosy, we’d be hearing steelhead jumping and people would be out here fishing right now. They’re not. And [the Skagit] used to be a stronghold [for steelhead] for the Puget Sound.”

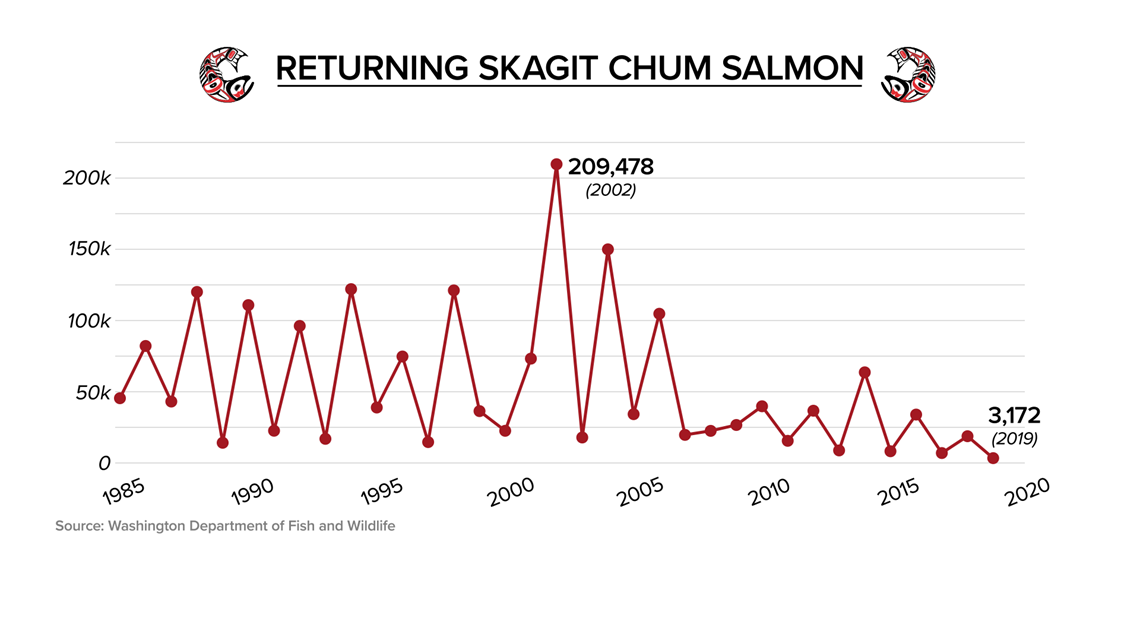

City Light’s online messaging trumpeted the utility’s “carefully” regulated flow rates of the river (beginning in the 1980s) below their dams, and that “salmon are responding to our efforts.” The utility held up the chum salmon species as a “Skagit Success” story: “Since 1985, the upper reaches of the Skagit River below the hydroelectric project have seen an eight-fold increase in chum salmon,” wrote website authors. “The chum salmon return of 210,000 in 2002 was the largest return on record.”

Thirty-year Seattle City Light customer Lori Winnemuller, of West Seattle, said the city’s message looked impressive.

“I would think that it is incredibly successful… and I would think, ‘wow, somehow [their dam operation] has made things possibly even better than it was before.’ [An eight-fold increase in chum] sounds incredibly good,” Winnemuller said.

According to state data, chum did have an epic year in 2002, but that was nearly 20 years ago. The utility did not furnish updated information for the public to show that chum salmon are barely hanging on in the Skagit. Since 2002, there has been a steady decline in chum returning to the river, with 3,127 counted by WDFW in 2019. That’s a 67-fold decrease in chum salmon returns since 2002 the utility did not include.

“That feels incredibly deceptive to me and irresponsible because [ratepayers] need to know what the impact is,” Winnemuller said. “We’re not getting the full picture here.”

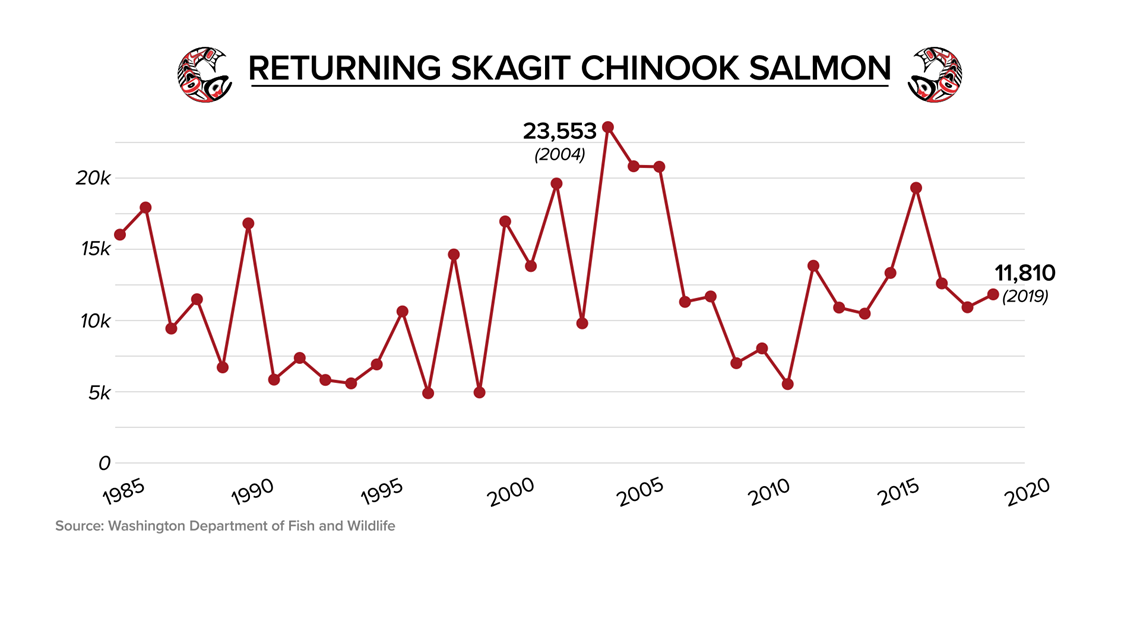

The public did not get the full picture regarding Chinook salmon either. City Light’s website highlighted “strong returns of chinook salmon. The return of 25,000 Chinook to the Skagit basin in 2004 represents a landmark event, the largest return in 25 years.”

But KING 5 has found since 2004, Chinook have steadily declined on the Skagit. In 2019, according to WDFW data, 11,800 returned to the river to spawn. That’s less than half of the record numbers posted by the utility.

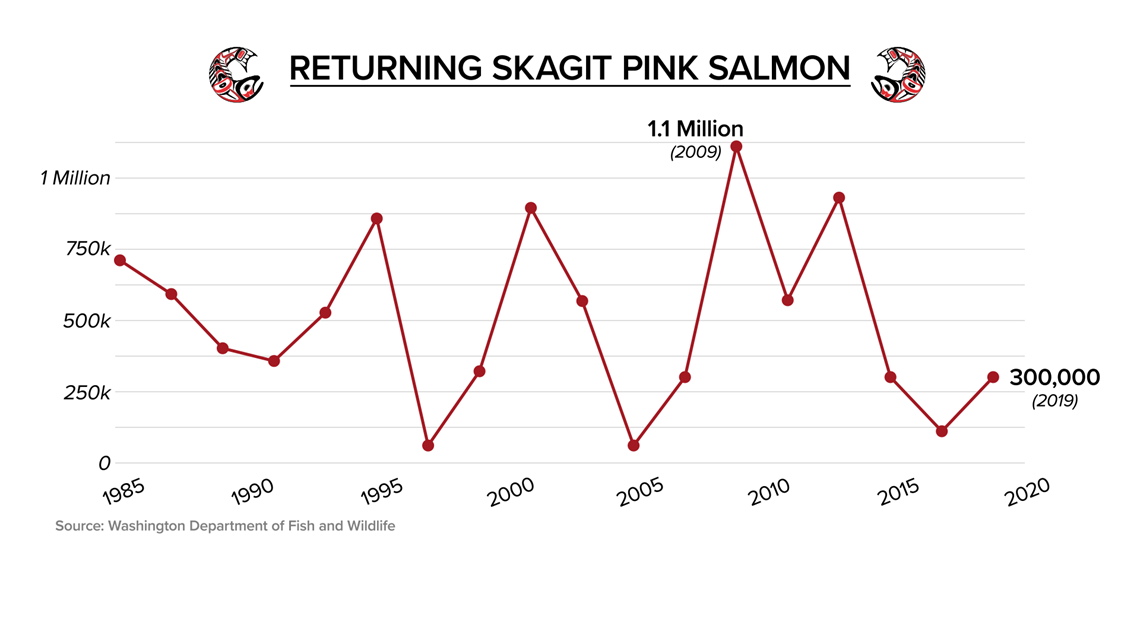

The website highlighted a "record" pink salmon run in 2009. Current data shows the species in decline.

In public documents filed in December, Seattle City Light featured data showing their change operations in the 1980's "progressively increased" populations for salmonid species, including Chinook salmon. The data was part of the city's documentation submitted to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the agency charged with re-licensing hydropower projects.

In a February public meeting biologists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA Fisheries) took exception to the utility continuing to highlight years in which salmon runs improved, while omitting data showing declines in more recent years.

In a power point presentation, NOAA biologist David Price asked: "If City Light operations are responsible for increasing abundance (of Chinook salmon) before 2004, are they also responsible for the decrease since 2005?"

The public utility’s top executive said there was no design to mislead federal hydropower regulators or the public, but that could have happened, unintentionally.

“I can tell you we are not attempting to mislead. But if we don’t have the current information or the full picture [in our public messaging], we could, in fact, be having that impact without intending to,” said Seattle City Light General Manager and CEO Debra Smith. “You’ve shared some information with me that causes me to want to go back and make sure we are being transparent.”

A KING 5 investigation launched last month revealed city officials have a long history of denying the utility’s dams hurt fish and wildlife – standing behind science, some of it 100 years old, criticized by tribes, state and federal regulators as “outdated,” “misleading,” and “not [holding] up to scrutiny.”

In the process, the utility has avoided spending millions of dollars to build additional infrastructure to help fish get over their dams, such as other utilities do via fish ladders or a system of collecting and trucking fish around the structures.

It’s well documented by federal agencies that dams hurt fish by blocking off river habitats they need for spawning and maturing. But Seattle City Light’s position has been that is not the case on the Skagit River because their research shows fish can’t swim past large boulders and steep grades below their project anyway. The city’s dams block off approximately 38% of the river.

The utility assured the public their dams weren’t blocking habitat for salmon in media interviews, online statements and public signage around the project.

On a web page entitled “Environmental Commitment,” now removed, the public utility linked to several positive news articles about its stewardship on the river from media outlets including a 2003 article from the Seattle Times. Below the links, the page asked readers: “Need more proof (about how we treat salmon)?” The additional “proof” included information about salmon never being able to navigate through the environment where their dams are now located.

“The historical spawning grounds for Skagit salmon are located downstream of the dams, below a natural fish migration barrier,” wrote City Light.

In 2016, a top Seattle City Light executive said in an interview with KING 5 that the utility lucked out when it was determined the dams had been built 100 years ago where salmon couldn’t swim anyway.

“The Skagit Project dams were fortunate enough to be constructed above a natural barrier for spawning fish,” then-manager of natural resources and environmental permitting for Seattle City Light, Colleen McShane, said. “That probably was not a conscious decision on the part of City Light. That wasn’t in people’s mindset at that time. That was pretty much pure luck that that happened.”

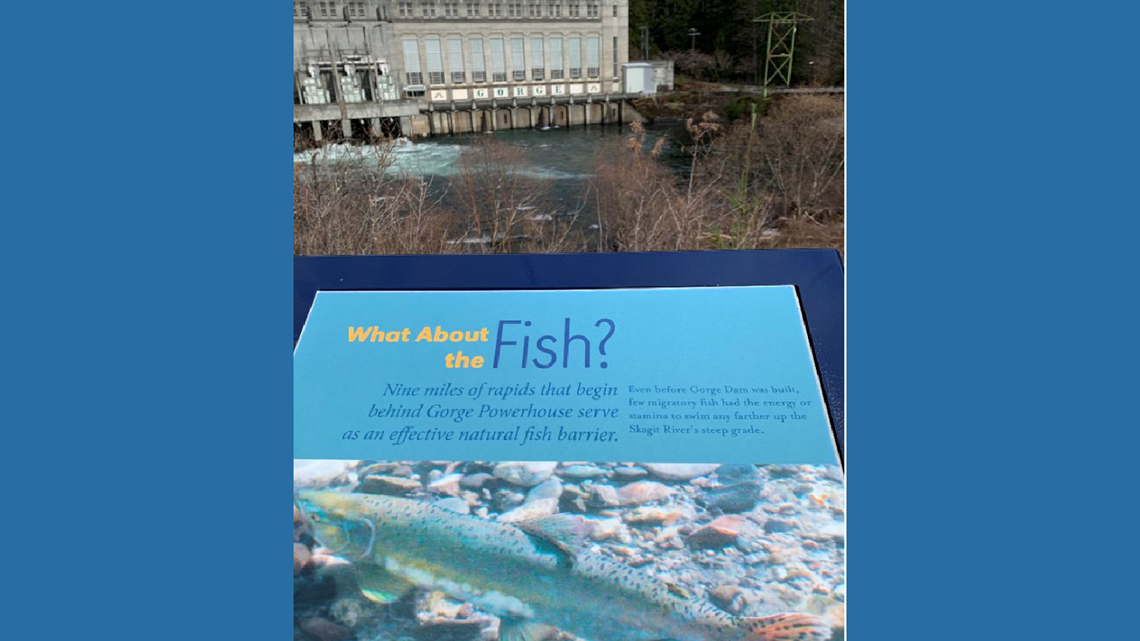

In signage that greets tourists to its hydropower plant in Newhalem, Washington, City Light asks the question: “What about the fish?” The answer on the sign references the nature-made barriers.

“Nine miles of rapids that begin behind Gorge Powerhouse serve as an effective natural fish barrier,” the sign reads. “Even before Gorge Dam was built, few migratory fish had the energy or stamina to swim any farther up the Skagit River’s steep grade.”

In public documents, state and federal regulators and tribal scientists wrote the message about natural fish barriers doesn’t hold water.

Scientists from the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) wrote Seattle’s dams “block access to historic Chinook salmon spawning and rearing habitat.”

“…no insurmountable [natural] barrier exists downstream of Gorge Dam,” wrote scientists from NOAA Fisheries. "The dam is the conclusive barrier for upstream passage and access to potential suitable habitat for anadromous species.”

Scientists from the National Park Service wrote they had surveyed the places where alleged natural impediments to migrating salmon were located and that they have “not found any evidence of a fish passage barrier” below Seattle’s dams.

After more than two years of firmly rejecting the idea of studying fish passage over all three of their dams in conjunction with the re-licensing process, Seattle City Light representatives agreed to a comprehensive study the day after KING 5 aired its first report in the series “Skagit: River of Light and Loss.”

The utility also proposed it be the “lead investigator” of the study.

City Light’s revised study plans for relicensing are due on April 7. They will cover a variety of issues related to mitigating for harm the project may be inflicting on fish, wildlife, recreational uses, and Native American cultural practices.

Seattle City Light said removing web pages questioned by KING 5 had nothing to do with the news reports.

“City Light launched an all-new public website on January 27, 2021. The new website was part of a wholesale redesign where we refocused on improving customer service and the highly used pages, while also condensing, updating and/or removing outdated information,” Jen Chan, Seattle City Light chief of staff, said. “Regarding the pages about the Skagit Hydroelectric project, those were in need of updating; as you noted, some of the documents had been there for years and were out of date. The public documents related to Skagit relicensing have been, and continue to be, available and can be found here: http://www.seattle.gov/light/skagit/Relicensing/default.htm.”

Ratepayers said they expect the city to mirror the values of the citizens it serves.

“At the end of the day, this utility is accountable to the citizens of Seattle and we have a voice here that we can hold them accountable to the standards that’s consistent with the values of our community,” aquatic biologist Tom O'Keefe, who is involved in the relicensing project and is also a City Light customer, said.

“We’re ratepayers. We’re stockholders. We’re shareholders and they need to do what’s right by the citizens,” Lori Winnemuller said. “I think that Seattle citizens would say the right thing is to make sure that the salmon are not impacted by those dams.”

Winnemuller said she called City Light after KING 5’s first report to voice her concerns as a ratepayer. She said she also filled out an online form where customers can raise issues.

“I haven’t heard back from them. I need to follow up."