SEATTLE — All the rain from this atmospheric river raises the risk of landslides on slopes around western Washington, although slides may not happen until after a big rain event.

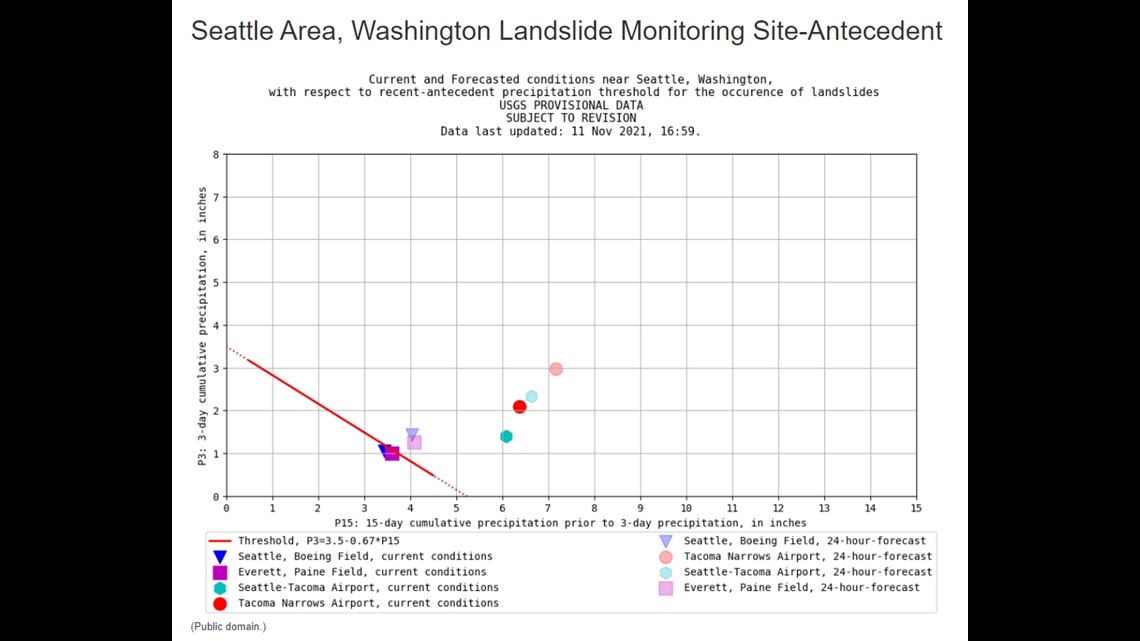

The landslide threshold from the U.S. Geological Survey from Thursday evening shows rain totals recorded at some key airports, from Tacoma Narrows, Boeing Field in Seattle, Sea-Tac and Everett’s Paine Field to the north in Snohomish County.

The further the airport’s symbol is above and beyond the angled red line, the likelihood of landslides goes up. The graph doesn’t just measure how many inches of rain, but how long that rain has had time to sink into the ground.

As the graph below shows, some spots, like the Tacoma Narrows Airport and Sea-Tac Airport, are in more danger of landslides 24 hours out from forecasted heavy rain than in the midst of a rain event.

Landslides, often referred to as “mudslides” or by their scientific name "debris flows," are the most common form of landslide during big rain events.

They happen after enough heavy rain manages to reach a layer of clay in the hillside. Since the clay doesn’t allow much of the rain to pass through, it breaks the bond between the clay and the soil above.

Once that bond is broken, the upper layers –by this time saturated and heavy with water, slide down hitting homes, undermining roads, blocking railroad tracks and coating what’s below with various thicknesses of mud.

Yet, while these conditions exist around much of the west side of the state, even in and around the edges of the City of Seattle, only some slopes will let go during a particular storm.

“There’s some evidence to suggest that it’s high-intensity cells of very intense rainfall to kind of localize how much extreme water falls on a particular place—and that’s really hard to predict,” said University of Washington geomorphologist Dave Montgomery.

Slides don’t necessarily come down during the heaviest rain, and may not release until after the storm is over.

“There’s often a time delay between the peak rainfall and the actual triggering of a landslide,” said Professor Montgomery.

The debris flow landslides we’ve grown used to are just one type that can be influenced by rain. The deadliest landslide in U.S. history happened on March 22, 2014, near Oso, Washington on Highway 530. The slide killed 42 people as a saturated hillside hundreds of feet tall collapsed, the mud racing at an estimated 60 or more miles per hour across the valley below taking out the Steelhead Haven residential community. Montgomery, who has studied that slide closely, says it can take rain a long time to soak deeply into the soil. The slide came after days of intense rains, following an already wet winter.

“A long soak sets up the conditions for that kind of a failure, but there can be a bigger time lag because it often involves time for the rainfall to percolate down to the groundwater table and make its way down to the zone of instability on those deeper ones,” he said.