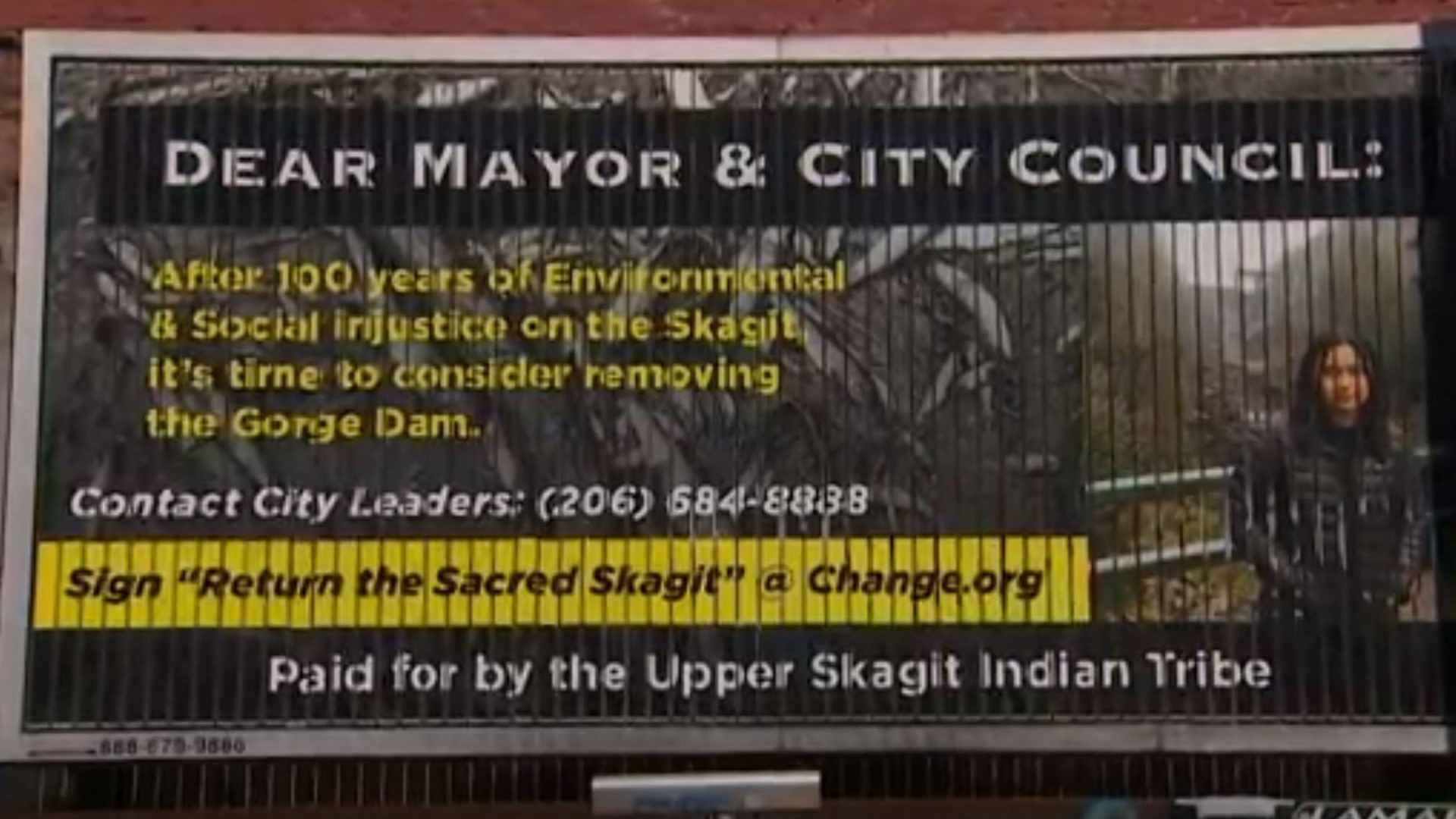

SEATTLE — Leadership of the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe, based in Sedro-Wooley, has put up a billboard in downtown Seattle to pressure Seattle officials to consider removing one of the city’s hydroelectric dams on the Skagit River.

The billboard features a young tribal member standing in front of Gorge Dam with wording in bright yellow that says: "Dear Mayor and City Council: After 100 years of environmental and social injustice on the Skagit, it’s time to consider removing the Gorge Dam."

For the last century, Seattle City Light has operated three dams on the Skagit to generate hydropower – which provides approximately 20% of the electricity for Seattle residents and businesses. But that cost-effective, carbon-neutral power comes at a cost to the Skagit Valley ecosystem and indigenous tribes.

The Upper Skagit Tribe said they were “forced” into a public call to action in the form of a billboard because they don’t think Seattle’s top officials, Mayor Jenny Durkan and members of the Seattle City Council, understand the trauma Gorge Dam and the hydropower operation inflicts on the tribe.

The city is in the process of having their dams relicensed by the federal government. Negotiations surrounding terms and conditions for a new license have been underway for two-and-a-half-years. As part of this process, in public documents and in person, the tribe has requested the city study the viability of removing Gorge Dam. So far, City Light has rejected their appeal.

“It leaves an empty spot in my heart right now that we can’t reach agreement. The tribe has done everything possible to get this study done,” Scott Schuyler, the Upper Skagit natural resources policy director said. “We just don’t understand the reluctance. The city council, the mayor, they have the ability to affect change. And the change starts with getting the assessment done.

KING 5 made repeated inquiries to Durkan and city council members, including to Council President Lorena Gonzalez for this report, but none returned emails or phone calls.

Late Thursday, the media liaison for the council responded to an email acknowledging council members were aware of KING 5's request.

"I’m not aware of any Councilmembers’ intention to respond. If that changes I’ll be sure to let you know," Dana Robinson Slote, Seattle City Council director of communications wrote.

Seattle City Light’s top executive answered questions about the request to study dam removal.

“At this point….my position, and that of the city has not changed,” City Light General Manager and CEO Debra Smith said. “(But) I have learned to never say never. The city’s position could change and if that was the case then we would obviously change but at this point we are moving forward with what we’ve discussed in the past (to relicense all three dams).”

Valley of the Spirits

According to the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe, Gorge Dam sits on the boundary of the tribe’s most sacred ancestral land. They refer to that stretch of the river and the lands around it as the "Valley of the Spirits" – where all life began for them.

“We’ve been very protective of our history and culture but in light of the disagreement over the assessment we’ve been forced to share more with the city of Seattle hoping that would change their mind,” Schuyler said. “Now they know. The ball is in their court. It’s up to the city leadership to make the right determination here and support the tribe and our culture and our history.”

In addition to blocking passage for salmon to access much needed habitat, for three miles downstream of Gorge Dam, City Light diverts all the water out of the river and instead shoots it through a mountain tunnel to generate more force as the water hits the turbines in the Gorge Powerhouse in the town of Newhalem. Tribal members are critical of the city for dewatering of this spiritually important portion of the river, which flowed freely prior to dam construction.

“It’s a tragedy. It’s sad to hear. It’s frustrating because this is a natural resource. It’s a part of the world and mother nature. As Native Americans, yes we take from the river, but we make sure to give back,” said tribal member Ryan Scarborough.

According to the tribe, Gorge Dam also causes cultural pain because it creates a reservoir behind it that has flooded out culturally important sites. These are places where the Upper Skagit lived and carried out their traditions since time immemorial. Now, the sites sit underwater, damaged and inaccessible.

“It does feel like an oppressive action. It feels like they’re forgetting about what damage hydropower can actually cause to a native people,” said 17-year-old tribal member Troy Peterson.

“Knowing it’s gone on this long kind of makes me angry, to know the environmental affects and the way it affects us,” said tribal member Rochelle Peterson.

The billboard in Seattle also features a black and white photo of dozens of dead fish. The photo was taken by a tribal biologist following a 2019 City Light drawdown of the reservoir behind Gorge Dam. According to a report written by the National Park Service (NPS), scientists who surveyed the dried-up reservoir at the time, between 4,039 and 8,283 fish were stranded and killed in the event. NPS also estimated at least 620 additional fish were entrapped and faced increased risk of mortality.

“That picture of all the dead fish is just a snapshot of the thousands and thousands of fish that are killed every day, every year by hydropower on the Skagit,” Schuyler said.

A spokesperson for Seattle City Light said the utility must release water from behind the dams for federally mandated maintenance and safety tests and that in this instance “no one expected that so many fish would be stranded.”

“This is a routine but infrequent test that is required every five years. Before the test City Light consulted with Tribal, federal and state agencies and filed a drawdown plan with FERC. Despite the advance plan review by City Light and other agency staff, the test resulted in an unanticipated stranding of numerous fish in upper Gorge Lake,” Julie Moore, City Light communications director wrote. “We have collectively learned from this incident and changed the approach to reservoir operations.”

When dam construction began on the Upper Skagit ancestral lands a century ago, no one consulted the Native Americans. To a marginalized people trying to hang onto their culture, the tribe said this is a form of environmental racism.

“We didn’t matter. We didn’t matter. And that’s environmental racism in my mind,” Schuyler said. He also said they still don’t feel like they matter to the city.

“The city leadership has always touted itself as being indigenous friendly, supported tribal rights, sovereignty and tribal issues and in this particular instance they have failed to support the Upper Skagit Tribe when they are in fact the purveyor of the harm. And not one city official that I can recall has ever stepped up and supported our tribe against the utility. So it’s really telling for us: ‘Where is everybody? Where are you folks?’" Schuyler said.

Smith of City Light said the public utility is doing all it can to repair the fractured relationship with the tribe.

“You should know we’re working hard with them to reestablish a relationship. To be responsive to them around their cultural areas and items of cultural significance,” Smith said.

Smith said it’s a difficult balancing act to respect the tribe and treaty rights while generating carbon-neutral power for the city.

“We believe that it continues to be in the best interest for the communities, for the state – from a regional and a carbon perspective to continue to generate the power that that project is able to do,” Smith said. “And even as I say that I can certainly understand from a purely tribal perspective that that may not ring true.”

Another person in a position of power with the Upper Skagit Tribe said that before the tribe opened up about their complex spiritual life, city officials did not have the full picture of the “cultural trauma” caused by Gorge Dam. Now that they know, and there is still no movement on a study of Gorge Dam removal, the person, who asked not to be identified, said the utility and Seattle elected officials are participating in “cultural genocide.”

“Cultural genocide is a really serious expression. My reaction to that is ‘Oh my goodness, that is certainly not our intent,’” Smith said. “The city of Seattle’s and the state of Washington’s relationship (with Native American tribes) – the history and where we’ve been – it’s not okay… And we’re all working hard to figure it out and to go forward and to change the relationships but also (improve) the level of respect and trust.”

The Upper Skagit’s billboard, located at 1st and Cherry in Seattle's Pioneer Square, features a photo of 20-year-old tribal member, Janelle Schuyler. She’s standing in front of Gorge Dam and the dewatered river. She said seeing her photo above the busy streets of Seattle was "humbling." Schuyler also said it should serve as a message that the small, rural tribe isn’t backing down from a powerful city and its utility any time soon.

“We’re glad this billboard’s up to raise awareness to get the help we need and the justice we deserve,” said Janelle Schuyler. “This is a fight that we’re not backing down from and they’re going to have to deal with us for a while.”